With techniques drawn from sport psychology you can retain more of what you learn, says musician and performance psychology expert Christine Carter

Coaches have long known the secret of objective performance feedback. By using video cameras, they can show their athletes exactly what they are doing. Once athletes are aware of a problem, they can immediately take steps to remedy it.

As a (mediocre) figure skater, I remember numerous instances where my coaches told me I was doing something strange with an arm or leg, but I did not have the ‘Aha!’ moment until I saw it for myself on the video camera.

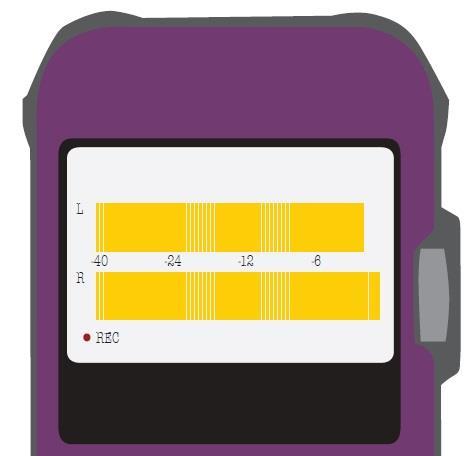

We have the same tool at our fingertips in music. Using a recording device can immediately show us what we need to focus on, especially during the majority of weekly hours when we do not have the luxury of expert coaching.

Even the expert coaches use this technique: so many of the great players I have interviewed depend on recording as a vital form of self-assessment. If recording is effective and cheap, why isn’t everyone doing it?

When I ask participants in my workshops to raise their hands if they think recording themselves would help them improve, almost everyone raises their hands. But when I ask who actually records themselves on a regular basis, very few hands go up.

The discrepancy between knowledge and action comes from the discomfort of having to face ourselves, weaknesses and all. A perceptual shift is required. We cannot fix what we are not aware of. Uncovering mistakes and problems in a practice recording can be exciting – this is the distance we have to improve.

There are two main ways to use recording in the practice room. The first is to record a short passage, listen, and record again, so that you have an immediate feedback loop. I recommend this form of recording as often as possible. Working in this way keeps the mind focused by providing yet another form of practice variation, while simultaneously building in breaks from physical exertion.

You will be amazed at how quickly you can fix problems. Don’t wait for the passage to be ‘good enough’. Start now. This process will tell you exactly what you need to know to make the passage good enough. The second approach is to record full run-throughs of excerpts or pieces and listen at the end of the practice session or day. I use this method in the weeks leading up to a major performance or audition. I play through the repertoire for the recorder, as I would on stage, and listen at home before going to sleep. I find it helpful to make notes on anything I would like to address the next day.

Throughout this process, it is important to be kind to yourself. Approach your own recordings as you would the recordings of a student – with compassion and a focus on what is going well, in addition to what needs to be tweaked.

Read: How to use ‘flow’ to make the most of your practice

Read: 7 views on repetitive practice

Read: How to use random practice to help long-term learning

This article was published as part of a larger feature on Practice Techniques in The Strad’s December 2012 issue. Click here to subscribe and login. Alternatively, download on desktop computer or through The Strad App.

No comments yet