Toby Deller speaks to the LGT Young Soloists artistic director Alexander Gilman about recording Philip Glass’s brand new Symphony no.14 ’Liechtenstein’, in this extract from the January 2022 issue

The following extract is from The Strad’s January 2022 issue Session Report ’Focusing the Lens’. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The January 2022 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

The famous wall at the front of Abbey Road Studios is looking particularly bright when the LGT Young Soloists come to record their album of Philip Glass. Not only is the fresh coat of whitewash barely marked by the otherwise perpetually blossoming Beatles graffiti, but also these are beautifully sunny summer days, a rarity for London in 2021.

Any mixed feelings the players may have about missing out on the sunshine, however, are not in evidence inside Studio One as they set to work on the brand-new symphony (no.14 for strings, titled Liechtenstein) that Glass has written for the group. For despite the symphony’s blissful, easy-sounding opening with which the second day’s recording begins, it is a piece of contrasting technical features that need to be executed with focus and attention to detail – and just as much in the more tranquil moments as in the fast passages of the finale. Concentration levels in the room are such that although I am only listening and am nowhere near an instrument, I still worry about ruining a take by merely thinking of playing an arpeggio slightly out of tune.

The group’s artistic director and concertmaster, Alexander Gilman, is clear that this is not music to be underestimated. He dismisses with a firm ‘No!’ the ‘mean voices’ who might claim, as he puts it, ‘“It’s Glass; you just go into the studio, you get the score and you sightread it.”’ In any case, his aspirations for the interpretation go beyond accuracy. ‘Minimalistic music is composed in a minimalist way, but I want to get the maximum out of this. I don’t just want to play plain, straight piano, I want to figure out where we can build a big phrase, where we can make different sounds, bring out the bass, bring out the viola. This is the biggest challenge.’

This approach, in his view, calls for meticulous preparation. ‘If you want to find this atmosphere – this beyond-the-world sense that you’re looking down to Earth – you need to think not only about which fingerings to use, but which bow speed, which bow division, which bow pressure, how you develop the bow speed – all those little things. Do you vibrate? Don’t you vibrate? And then you need your fellow musicians to do absolutely the same. That’s a real focus in rehearsals – mainly we focus on having the same bow division and so on. That’s why it’s good that the players don’t get distracted by a conductor and all eyes are ideally on me as the leader, or the soloist.’

Gilman’s preparation for the project included listening to Glass’s other symphonies – his first dates from 1992 and no.15 is scheduled for its premiere in March 2022. ‘I think this piece is not typical late Glass. It has a kind of transparency, some youthfulness and joy. But when I was speaking to him, I told him, if possible, he should try to mould it to us. He told me that he looked through our videos and said: “I’ve always worked with young people and this is exactly what I see in the videos – this joy, this energy.” I like how he put that into the piece. It’s still a signature piece, still typical Glass writing. But it’s quite different from his late works, especially the ending.’

Read: Session Report: Focusing the lens

Read: The Strad January 2022 issue is out now!

-

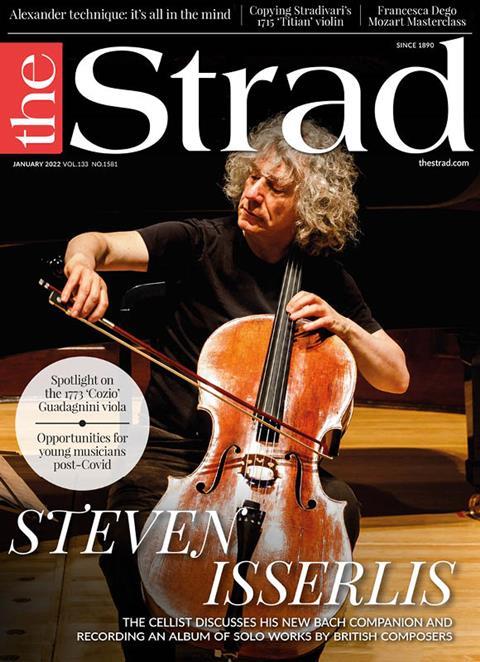

This article was published in the January 2022 Steven Isserlis issue

The UK cellist discusses his new Bach companion and recording an album of solo works by British composers. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Steven Isserlis on Bach and British composers

- 1773 ‘Cozio’ Guadagnini viola

- Alexander technique: it’s all in the mind

- LGT Young Soloists record Philip Glass

- Copying Stradivari’s 1715 ‘Titian’ violin

- Opportunities for young musicians post-Covid

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet