Gil Shaham reflects on collaboration and the versatility of contemporary music in three concertos written for him, here presented in their premiere recordings with Leon Botstein and The Orchestra Now.

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

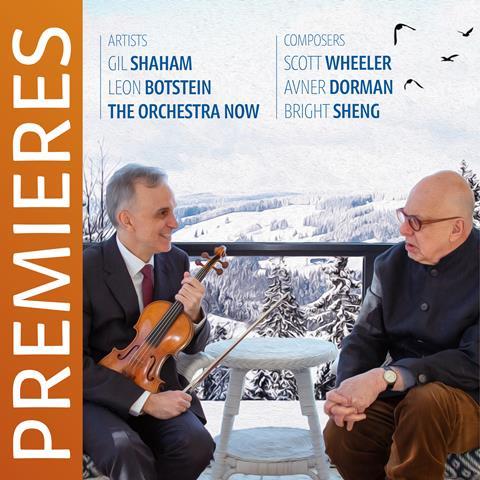

Premieres, Gil Shaham’s new release on Canary Classics, brings together three violin concertos written expressly for him and realised in close collaboration with conductor Leon Botstein and The Orchestra Now. Recorded at Bard College’s Fisher Center, the album reflects a network of long-standing artistic relationships and a shared belief in the concerto as a living, evolving form.

Scott Wheeler’s Birds of America, commissioned by Bard College for Botstein and The Orchestra Now, transforms avian imagery into a playful and poetic meditation on musical memory, weaving together birdsong, orchestral colour and fleeting historical allusions ranging from Vivaldi to jazz-era novelty.

Avner Dorman’s Nigunim, which began life as a violin sonata, distils shared modal gestures from diverse Jewish musical traditions into a concerto of rhythmic drive and spiritual intensity.

Bright Sheng’s Let Fly, inspired by Chinese ‘flying songs’ and by Shaham’s own sound, unfolds as a continuous three-movement arc and invites the soloist to shape an improvised cadenza.

Shaham spoke with US correspondent Thomas May about the album while preparing to perform Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto with the Philharmonic Orchestra of UNAM in Mexico City.

All three concertos on this album were composed specifically for you. How does bringing a tailor-made score into the world change your relationship to a piece, or to the composer who wrote it?

Gil Shaham: It’s incredibly thrilling to be part of that process of creation. I feel very honoured to have been involved in all three of these works. There are pieces I’d wanted to record for a long time, but it’s always difficult to find the moment when everything aligns – the right conductor, the orchestra, the producer.

In this case, it really came together thanks to Leon Botstein’s vision. Through our conversations, we arrived at the idea of recording these three pieces together. I think they contrast beautifully with one another.

These works also span a long stretch of time. You premiered Scott Wheeler’s Birds of America in 2021. Bright Sheng’s Let Fly goes back to 2013, with Leonard Slatkin and the Detroit Symphony Orchestra. Avner Dorman’s Nigunim began life as a violin sonata you premiered with your sister Orli in 2011 at the 92nd Street Y, before you introduced the first orchestrated concerto version in 2014. How do you look back on that arc now?

Gil Shaham: Each piece has its own history, but they’ve all stayed close to me over the years. Let Fly is the longest of the three, and it has a very expansive feel. With Nigunim, I’ve lived with the music for a long time in different forms, and it’s grown and evolved along with me. And Birds of America is the newest, but it feels very fully formed and very personal.

In Birds of America, Scott Wheeler weaves in little cameos ranging from Vivaldi’s Spring to Schumann’s prophetic bird to the jazz novelty tune The Hot Canary. How did you react to first encountering these allusions in the score?

Gil Shaham: I’d known Scott for several years before this piece, and one of the remarkable things about him is that he writes in many different styles. When he first sent me sketches for the concerto, I genuinely didn’t know what to expect. He told me early on that he was thinking of calling it Birds of America, like the Audubon book, and in fact he ends up quoting something like 23 different bird calls.

But he does it very differently from someone like Messiaen. There are these allusions that are sometimes playful – meant to bring out a smile – but they’re always handled with great subtlety and always in the service of the overall feeling he’s creating.

The Hot Canary, which I love anyway, adds a romp-like touch to the final movement. Other references carry different meanings. And then there’s the slow movement, which has this hauntingly beautiful melody. To me, the piece has a very American voice. Scott really does make it Birds of America.

Avner Dorman builds Nigunim from shared musical DNA across Jewish traditions, without quoting any single melody. The Hebrew word ‘nigun’ refers to a wordless song intended to transcend language and convey spiritual meaning. After more than a decade with the piece, is there a gesture or moment that still feels especially personal to you?

Gil Shaham: Avner is such a brilliant composer. It may sound like a cliché to say that music brings people together, but in my experience, it really does – especially when you’re working closely with a composer on a new piece. That kind of collaboration creates a special bond.

When we were planning the programme at the 92nd Street Y, we wanted to focus on concert music based on traditional Jewish material. Avner spoke from the very beginning about being drawn to the music of the lost tribes of Israel, and he gravitated towards Sephardic traditions. He explained that the first movement draws on Libyan incantations, the second on Georgian dances – particularly wedding dances – and the final movement has this exuberant Balkan 7/8 feel.

Orli and I loved the piece from the start and still do. I’m thrilled that other violinists took it up fairly quickly. At some point, I suggested the idea of orchestrating it as a concerto, and Avner embraced that. Somehow, the piece reminds me of my childhood in Israel – of hearing Sephardic and Arab music – and that personal resonance has never faded.

Bright Sheng’s Let Fly gives the soloist the unusual freedom to create their own cadenza. What was your process in shaping yours? Did you lean into the idea of the ‘flying song’, or did you find yourself chasing a different kind of energy?

Gil Shaham: When I first saw that instruction in the score – a short cadenza to be improvised by the soloist – I felt quite anxious. I told Bright, ‘I don’t normally write music, and I don’t really improvise. Why don’t you just write the cadenza yourself?’ But he was very firm: ‘No, I want you to do it.’

I wanted the cadenza to feel organic, not something that came out of nowhere. My goal was to connect the end of the slow movement to the beginning of the third movement, to create a sense of flow. Bright was incredibly generous and gracious, and in the end he even printed my cadenza in the score.

He also told me about the tradition behind the title – the mountain singing in southern China, where people belt out songs across valleys to be heard from one mountaintop to another. I found that image completely captivating. The opening of the piece comes directly from that idea, and much of the music is also based on a little song Bright used to sing to his daughter when she was a baby.

Bright Sheng has said that Let Fly was inspired by an image of your playing – ‘the aural image of the violin melody just flying off in the air – an everlasting sensation when I first saw Gil Shaham perform a concert’. What images does that correspond to for you when you play this music?

Gil Shaham: Bright makes the orchestra sound splendid, and he makes the violin sound splendid. The opening statement of the melody is entirely on the E string, soaring above the orchestra, marked fortissimo – that may be part of what he had in mind. There’s also a section where the orchestra plays the melody while the violin floats above it in harmonics, covering a whole spectrum of colour. That sense of flight is really built into the music.

In rehearsal or in the recording sessions with Leon Botstein and The Orchestra Now, was there a single moment that changed how you understood a passage in any of these works?

Gil Shaham: I remember a moment when Leon and I were discussing a particular phrase, and he said, ‘Gil, I feel like this really starts on the second beat – the first beat is actually the closing gesture of what came before.’ I looked at it again and realised he was absolutely right. We checked it with Bright, and he agreed. Those kinds of insights can completely change how a passage feels.

What was the through-line that inspired you and Leon Botstein to bring these three concertos together on the same album?

Gil Shaham: They contrast nicely, but they also complement one another. All three composers make the violin sing, and there’s a shared sense of lyricism, even though each piece speaks in its own language. Together, they felt like they belonged.

What other projects are you involved with at the moment?

Gil Shaham: We’ve just recorded Mason Bates’s Nomad Concerto with the Nashville Symphony and Giancarlo Guerrero. I’ve also recorded the Coleridge-Taylor Violin Concerto, Dvořák’s Violin Concerto and a piece by Curtis Stewart with the Virginia Symphony, from live performances.

We also premiered Avner Dorman’s Double Concerto, which he wrote for Adele [Anthony] and me, and I’ve just received part of a new Double Concerto for piano and violin by Reena Esmail – what I’ve seen so far is absolutely gorgeous.

Premieres is available 19 December on Canary Classics.

Read: The Shaham siblings explore Clara Schumann and her circle

Watch: Gil Shaham on the advice he received from mentors

Read: Premiere of the Month: Avner Dorman’s new double concerto for Gil Shaham and Adele Anthony

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

No comments yet