The annual La Ruta de Mozart festival presents the composer’s complete string quartets in a day of celebration at open-air locations around the city of Havana. Chloe Cutts attended this year’s edition

The Alma Quartet gives an al fresco performance. Photo: Annelis Liens Puentes

Havana’s oldest square, the 500-year-old Plaza de Armas, has seen many historic events in its time, but it is unlikely to have witnessed Mozart’s string quartets being performed in the open air until the arrival of La Ruta de Mozart festival in 2018. US-born violinist, teacher, conductor and festival director Michael Dabroski’s single-day celebration of the composer’s complete string quartets at locations across Havana’s historical district is part Mozart marathon, part walking tour, but Dabroski’s ambitions for the event reach far beyond simply providing a musical distraction for footsore tourists and interested locals. His goal, he explains, is to help build a diverse and sustainable musical infrastructure in Cuba.

‘Western classical music has been around in Cuba for a long time, and there are multiple conservatoires across the country. But it has not infiltrated Cuban life to the point where it has become a sustainable and self-governing economy to fulfil a greater opportunity,’ Dabroski tells me at the Casa de Carmen Montilla art gallery, another La Ruta venue, where the Caturla Quartet has just finished performing Mozart’s ‘Spring’ Quartet K387 in a standing-room-only auditorium.

This situation is not for want of musical potential, as Dabroski discovered when he moved to Cuba last summer following his tenure as founder and director of the Vermont Mozart Festival. ‘I was amazed by how much enthusiasm there was for this music among the students I taught here,’ he continues. ‘In Cuba all children receive intensive music training from a very young age as part of their schooling, and among the young players I saw such natural musicality, such maturity, and such a strong sense of rhythm and metre coming from Cuba’s traditional musical heritage.’

The idea of launching a compact, socially minded festival offering students repertoire training while serving the wider community through free concerts comes at a time when Cuba is experiencing an upsurge of interest in classical music. The musicians of the eight string quartets performing at this year’s La Ruta are all affiliated with the Mozartian Lyceum of Havana, a music school established in 2009 to give additional training to graduates of the University of the Arts (ISA), Cuba’s foremost music college. The Lyceum is supported by the Salzburg Mozarteum Foundation of Austria, and is a significant player in the recent history of Western classical music in Cuba. Through its programmes, students receive professional orchestral training as members of the Havana Lyceum Orchestra, which includes professionals and which under director José Antonio Méndez Padrón has performed in Europe and toured the US. In 2015 it gave the first performance in Cuba of Mozart’s Mass in C minor K427, in Havana.

The Lyceum also indirectly led to the founding of La Ruta, because the idea behind the festival came from the Lyceum-trained musicians of the Crisantemi Quartet when they performed at Dabroski’s Vermont Mozart Festival in 2017. The group’s first and second violinists, Danielle González Sánchez and José Luis Rubio Reyes, co-direct La Ruta and are shining examples of the qualities of Cuban musicianship Dabroski speaks about. At a pre-festival reception hosted by the Austrian Embassy the quartet performed a programme of Cuban piano music transcriptions, Entreverao de arcos by Venezuelan composer Orlando Cardozo, and Mozart’s String Quartet K589, here played with undemonstrative simplicity.

- Read: Brahms among the Palms: Postcard from Boca Raton

- Read: Grand Designs: Postcard from the 2016 Piatigorsky International Cello Festival

- Read: The promise of Youth: Postcard from London

Dabroski spent the three months leading up to the festival personally tutoring each of the quartets in their programmes – quite a feat, but one that paid off in performances that showcased Mozart’s music with enjoyment, communication and musicality, often with significant noise-offs and, late in the afternoon, the accompaniment of torrential rain. ‘Most of the musicians have been surrounded by Mozart throughout their education and have significant experience in this repertoire. Others were learning their quartets for the first time, so José [Reyes, assistant festival director] and I tailored the programmes accordingly,’ says Dabroski, before adding, ‘Mozart’s string quartets are all difficult and represent a significant challenge to the interpreter.’

Dabroski clearly has a strong rapport with the musicians, who he regards as colleagues. At the rehearsal for the final concert, a massed quartet performance involving all the participating quartets at the Church of San Felipe Neri, it was a pleasure to see the spirit of camaraderie among players and director as he spotlighted areas of rhythmic articulation that needed tightening, phrases that called for more restraint, and points of climactic emphasis in the quartets K80 and K499, not to mention difficulties with intonation (Havana is hot and humid in February). The church’s acoustic allowed the warmth of the playing to be conveyed with youthful energy and lightness of touch in the ‘Hoffmeister’ K499, particularly in the bracing, vital final movement.

‘They’re playing with minimal supplies, and could use better instruments, strings and bows,’ says Dabroski when I ask him about the availability of instruments in Cuba. Lyceum concertmaster Danielle González Sánchez, who currently studies in Berlin, is fortunate to have the use of an instrument on loan, and at the final performance she played a new violin made by Havana luthier Juan Carlos Prado Castro, commissioned by Dabroski and built in Cuba’s only fully functioning stringed instrument making and repair workshop, on Plaza Vieja. The workshop was established by the Belgian luthier Paul Jacobs, founder of Luthiers without Borders, who brought money, strings and machines, and paid for apprentices to take six-week training courses in Italy and Spain. Many of the string students here play on instruments donated to the Lyceum directly or via Luthiers without Borders.

The Crisantemi Quartet will disband following the festival, when Sánchez and Reyes depart for Europe to continue their music training. This highlights a conundrum: how do you retain the best musical talent in Cuba? The answer, Dabroski says, is to create a strong musical economy that creates openings. He is not the only musician to attempt this – La Ruta inaugurated a year after the arrival of Habana Clásica, a crowdfunded international chamber music festival directed by ISA-trained Marcos Madrigal and presented by several cultural institutions within Cuba. What makes La Ruta de Mozart different, however, is its emphasis on enabling musicians to become their own enterprise, and in this respect the string quartet has the upper hand over orchestras and opera companies.

‘The idea of a string quartet festival is certainly niche, but it supports the needs of Cuban musicians to travel outside Cuba, and thereby advertise Cuban musicianship, in a way that is financially feasible,’ says Dabroski. ‘In a string quartet artists become their own managers; it is a musician-led ensemble, and also portable. Musicians work on their own initiative to form a quartet and they choose what repertoire to play. Creating educational systems allows promising string players to hone their critical and leadership skills and from there they can build sustainable musical projects.’

The festival has the support of the Mozartian Lyceum of Havana and the Austrian Embassy: both view La Ruta as fulfilling a genuine need in Cuba, and Dabroski sees no reason why the festival cannot be replicated anywhere in the world. ‘My plans are consistent with their mission in Cuba: to establish audiences for Mozart and raise the level of musicianship here,’ he says. ‘There can be an enhanced musical economy here, with workshops, concerts, audience-building. The popular Cuban styles thrive here, and there are composers writing new, inventive music. It’s not just about the sound; music has to involve a social benefit if it is to thrive.’

-

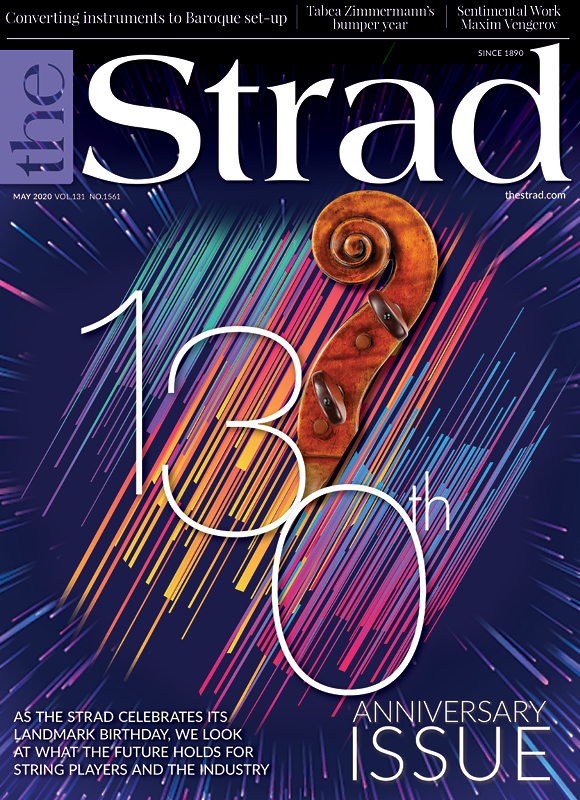

This article was published in the May 2020 130th Anniversary issue

The Strad marks its 130th anniversary with a look at the future of string playing and the violin industry. Explore all the articles in this issue.

More from this issue…

- A look at the future of string playing and the industry

- Violist Tabea Zimmermann on her bumper year

- Converting an instrument to Baroque set-up

- Making a career in music therapy

- How luthiers can avoid repetitive strain injury

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet