The cellist of the Latin American Quartet shares memories of tough love and camaraderie with his former teacher, who died in 2013

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

This article was written in response to Memories of János Starker: Hamilton Cheifetz

At the age of 18, I had the privilege of being accepted into the class of the legendary cellist János Starker at Indiana University.

Starker was without a doubt one of the most important cellists of the 20th century, and I consider myself very privileged to have been his student.

The three years I was his disciple were, without a doubt, the most important in my musical formation, and his teachings were so abundant that even today, more than 40 years later, they still exert their power and bear new fruit.

Until shortly before his death, we stayed in touch by phone or mail, as he used to send me comments on each new album I sent him.

The last thing I received from him was a card (as always, handwritten) commenting on my most recent delivery: a DVD by the Latin American Quartet titled Visiones, in which we performed twelve Latin American pieces filmed in various locations. His card said, literally:

’The playing is excellent. As far as some of the pieces, the man is too old for them. Hope it sells — Starker’

János Starker was a man who smoked compulsively throughout his life, so the news of his death at 88 in 2013 after a prolonged illness did not come as a surprise.

Still, knowing that he is no longer in this world brought about a shift in me and triggered a chaotic symphony of memories and anecdotes in my mind—some of which I’ll attempt to record below.

The first time I saw him in person I was 16, at the Palacio de Bellas Artes in Mexico City, back in 1974, performing the Saint-Saëns Concerto with the National Symphony Orchestra. I remember very little of the concert, but I will never forget that afterward, I dared to ask him for an autograph. And though there were several of us waiting in line, when it was my turn, Starker looked me straight in the eyes and gave a faint smile before signing. That small human gesture meant a great deal to me.

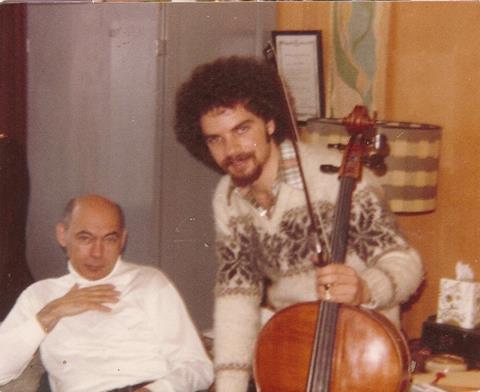

I admired him so much that, in a typically teenage move, I took a programme photo imitating his.

Two years after that episode, I had my first lesson with him at Indiana University. That first day, I woke up very early and arrived at school by 8:00 a.m., even though my lesson was scheduled for 9:00.

After practising until 8:50, I made my way to his studio, behind a door bearing the impressive plaque ’János Starker, Distinguished Professor of Cello,’ where a new chapter in my life would begin.

At 8:55, I finally dared to knock. Getting no reply, I opened the door. The first thing I saw was Starker sitting at his desk, wearing black-rimmed glasses (something I had never seen or imagined him with), reading some documents.

I stood there waiting for a greeting or instruction. Receiving neither, I entered and closed the door. In complete silence, I unpacked my instrument and sat in the chair in front of the music stand. By then, the wall clock read 8:57.

Starker remained focused on his reading, and I didn’t know what to do except remain silent and grow increasingly nervous. The next three minutes felt like the longest of my life. Finally, at exactly 9:00, Starker looked me in the eye and said:

’Good morning.’

By then, I was a bundle of nerves and proceeded to play the first solo from the Brahms Double Concerto.

After the two-minute fragment, Starker said:

’It’s out of tune, the sound is ugly, it’s not musical. In other words: it stinks. Go home and practise.’

That was my first and unforgettable lesson with János Starker.

Hours later, my parents called from Mexico, excited to know how it went.

’Pretty well,’ I lied.

That was the first of many difficult moments I would experience and witness in his studio. But I soon realised that to be there, one needed a strong character and a warrior spirit—and that by demonstrating those qualities, you would gradually gain ground in the rocky terrain of his affection. And that’s exactly what happened to me. After a tough first semester, I began to earn his warmth, and things got better.

Every Saturday at noon, when Starker wasn’t traveling, he held his legendary public masterclasses at the university, in which six to eight of us would perform.

These classes were terrifying, as the maestro would unleash the full power of his irony. But each student had to go through it at least once a semester—and the experience was unforgettable.

What I remember most, however, was a cold February morning when the small town of Bloomington was buried under half a metre of snow. We were all sleepy, cold, and likely underslept.

The first victim played the opening movement of the Schumann Concerto. When he finished, Starker silently put out his cigarette, stood up, and made his trademark gesture: hitching up his pants at the hips with both hands.

Then he took out his cello, wiped it briefly with a grey cloth, rosined his bow, and walked to the chair. He sat down and, with a subtle lift of his (famous) eyebrows, signaled the pianist to begin. What we heard next I’ll never forget:

The opening phrase of the Schumann concerto, played with absolute technical precision—and something rarer: his heart.

That morning, for reasons unknown to us, we heard the most emotional, passionate, and sincere Starker I ever heard. Something must have stirred him. It was so perfect and moving that when he finished, no one said a word.

He too stayed silent, got up slowly, and put his cello away.

Then, suddenly, something strange happened: as if on cue, we all began to applaud in unison.

Starker, who was now putting away his cello, turned around, made a dismissive hand gesture toward the audience, like meaning:

’Bahh!… Not that big a deal.’

Without a doubt, the greatest opportunity life gave me to spend time closely with Starker came during a trip to Chile.

While on vacation with my family in Chile in 1978, I happened to coincide with a concert tour Starker was giving in the south of the country. Since I was his student at the time, the tour organisers hired me to accompany the maestro throughout the journey. My job was to translate and assist him however needed—carry his cello, help with hotel check-ins, etc.

And so began an unforgettable adventure aboard a train through southern Chile that lasted five days.

That trip gave us lots of free time and the opportunity to talk about much deeper subjects than we ever could in the academic setting. As the Andes passed by our window, he told me much about his life—including his tough Jewish childhood and the hard times working as a forced laborer for the Nazis during the Second World War on a Danube island near Budapest called Csepel.

Another great privilege in my musical life was playing Schubert’s glorious String Quintet with Starker and my Latin American Quartet. It happened in Pittsburgh in 1990, while we were quartet-in-residence at Carnegie Mellon University.

During that concert, a small but unforgettable moment occurred: In the middle of the Adagio, there’s a very long pause. In it, Starker got distracted and came in early—an ugly mistake that was very obvious to the packed audience.

At the end of the movement, during the inevitable coughing break, Starker leaned over and whispered in my ear:

’The man is getting old…’

The last time I saw him was when I was invited by Indiana University’s Center for Latin American Studies to serve on a cello competition jury.

Taking advantage of the occasion, Starker asked me to give a cello masterclass—which I couldn’t refuse, though I was very nervous. The class was well attended, but luckily, he wasn’t able to come.

That same morning, in a totally unexpected gesture, Starker invited me to his house to chat, ’with a good bottle of scotch.’ The offer was tempting, but I had the class to give in just a couple of hours. I thanked him and declined. He insisted:

’You don’t deny a drinking proposition to your old prof!’

But, with much regret, I had to say no.

That left a bitter taste I never got rid of—but I couldn’t have done otherwise.

Afterward, we had a few more brief phone conversations—just greetings and formalities.

Then one day, the news of his passing arrived, bringing with it an avalanche of memories.

What remains, however, is much more enduring than any anecdote: a wealth of clear ideas about the cello.

Among them, a precise understanding of left-hand technique—and the certainty that bow technique is something much more subtle and mysterious, tied directly to the sound each cellist longs to produce.

I also learnt that there will always be someone who plays better—and someone who plays worse—so the only valid competition is with oneself.

And that never ends.

All photos courtesy Álvaro Bitrán.

This article was written in response to Memories of János Starker: Hamilton Cheifetz

Read: Starker at 100: Steven Isserlis remembers cellist János Starker

Read: Starker at 100: Gary Hoffman remembers cellist János Starker

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

In the second volume of The Strad’s Masterclass series, soloists including James Ehnes, Jennifer Koh, Philippe Graffin, Daniel Hope and Arabella Steinbacher give their thoughts on some of the greatest works in the string repertoire. Each has annotated the sheet music with their own bowings, fingerings and comments.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet