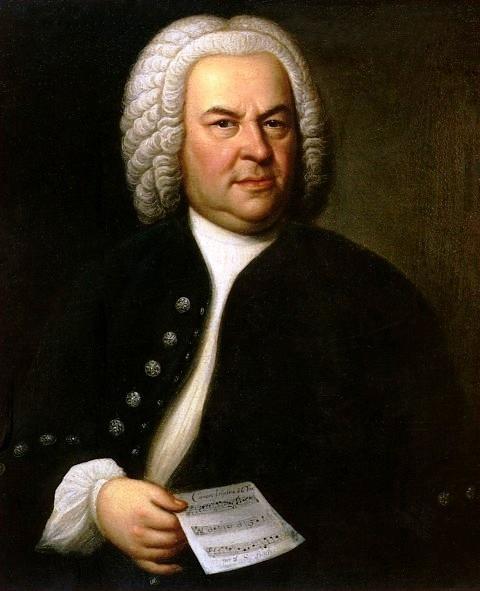

Following analysis of Bach’s Partita no.1 in B minor BWV1002, Lewis Kaplan introduces the mighty Partita no.2 in D minor BWV1004 in this extract from the August 2021 issue

The following extract is from The Strad’s August issue feature on Bach’s solo violin partitas. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The August 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

Moving on to the Second Partita in D minor BWV1004, at first glance it appears that Bach follows the book, with everything as expected – Allemande, Courante, Sarabande and Gigue; but then there’s a shocking surprise! There’s another movement at the end, the Chaconne, one of the greatest solo works in all music: Mendelssohn and Schumann added piano accompaniments, Brahms transcribed it for the piano left hand and Bartók paid homage to it in the opening movement of his Solo Violin Sonata.

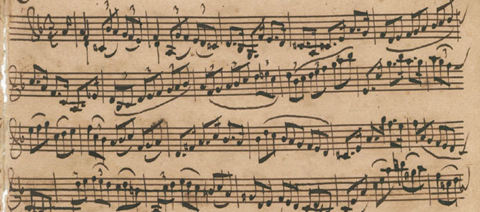

But we are getting ahead of ourselves. Let’s go back to the Allemande here, which like the Allemande of BWV1002 has a short up-beat and features a triplet running figure. It is perhaps because of its key of D minor a bit more serious than the B minor Allemande. The Courante has its up-beat gesture running throughout the movement (example 3). There is an important question relating to the execution of the dotted figure that first appears in bar 3. I believe it is intended to be played as a triplet rather than as a true dotted quaver semiquaver, which gives it a happy, lilting feeling as opposed to an angular nervous one. The Sarabande’s gesture again typically leads to the second beat of each bar and is bowed up–down–down. Bach again employs a four-note descending scale figure which plays a prominent role harmonically, as in the bass part of bars 3 and 4, and melodically, in the soprano in bar 4. The Gigue is in 12/8. Bach also writes gigues in 3/8 and in 6/8, as in the Third Partita. It is a lively dance with a jaunty up-beat and a swaying motion in the first two bars between the expansive quaver motion of the first and second beats and the third and fourth beats with their semiquaver interjections. Bach could have ended Partita no.2 here, having written a delightful four movements, but instead he adds a 14-minute profound essay: a masterpiece for all time.

So, what is a chaconne and what makes this one such a monumental work? It is a dance in triple metre, similar to the sarabande in character, tempo and gesture. There is, however, a major difference: the chaconne is a theme and variations. It is constructed over an ostinato bass, which is effectively a chord progression. Bach uses one of his favourite patterns, a four-note descending scale figure (basically D–C (or C sharp)–B flat–A) – the same notes and in the same key as Corelli’s ‘La folia’. Comparing the two demonstrates the breadth, scale and complexity of Bach.

Bach’s use of different versions of the four-note scale figure alone, although enormously impressive, would be only a partial display of his genius. Add to this his use of harmony, the way he changes the chord progressions at will, always with logic and extraordinary imagination; his thematic material, building variation upon variation; his sense of proportion, knowing when he has explored an idea to its limit and when to introduce a new one. However, dear violinist, if the harmony is not in the forefront of the interpretation, much of the greatness is lost

Read: Did Bach dance? Stylised dance in his Solo Violin Partitas

Read: Bach Solo Violin Partitas: Lord of the dance

Read: When Kyung Wha Chung met Bach’s Solo Violin Sonatas and Partitas

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #3: Benjamin Baker on performing solo Bach

-

This article was published in the August 2021 Esther Yoo issue

The American violinist on competitions, collaborations and the importance of maintaining a positive outlook. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- American violinist Esther Yoo

- The benefits of an adjustable violin neck

- Bach’s Solo Violin Partitas

- The Herrmann bow making dynasty

- Female violinists in 18th-century England

- Making accurate arching templates

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet