Following his analysis of Bach’s solo violin sonatas in the July issue, Lewis Kaplan discusses the elements of dance found in the solo violin partitas

The following extract is from The Strad’s August issue feature on Bach’s solo violin partitas. To read it in full, click here to subscribe and login. The August 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now

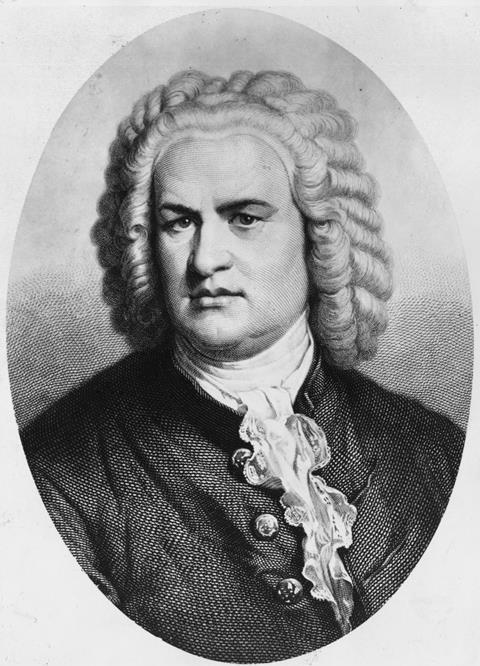

Did Bach dance? The answer to that question is unknown, but what we do know for certain is that he was familiar with the dances of his time. Probably he saw them performed at weddings or other social gatherings while growing up in Eisenach, and he may even have performed music at court dances in Weimar. This would have been useful to him when he set about writing his suites or, to use the German name, partitas, works comprising several dance movements that together create a larger structure. In his three unaccompanied partitas for solo violin, Bach created virtuosic works which display his enormous creativity: no two are alike, with each taking a different form and encompassing an enormous emotional range. His harmonic writing, as always, has no peer.

The most typical set of dances in a Baroque suite or partita are allemande, courante, sarabande and gigue. They are not meant as music to dance to; instead, they are stylised dances, or works retaining the elements of each dance form, including metre, tempo and gesture, but brought to a more sophisticated level. My favourite analogy of something that has become similarly stylised is jeans, which nowadays are worn by most of us. Jeans were invented by Levi Strauss in the 1860s for men doing hard physical work – cowboys, lumberjacks and railway workers. The denim material was strong, they were tight so as not to interfere with one’s work and the stitching was reinforced with copper rivets to prevent tearing. About a century later, along came some famous fashion designers who retained the coarse, tight look and big pockets, but who used much finer material and refashioned the design as a more contemporary look. Now, instead of the original modest cost, one paid a king’s ransom for the honour of purchasing them and wearing them to a cocktail party.

Now, Bach didn’t invent stylised dances; he had some talented predecessors – Biber, Westhoff, Pisendel and others – to give him a model and do some initial groundwork. Instead, he brought these dance forms (just as he did with other musical forms) to their highest level, magically interweaving moments of quite danceable music with more sophisticated commentary on the dances. Herein lies the great joy in performing and listening to Bach’s take on stylised dances.

Read: Yehudi Menuhin’s marked-up copy of Bach’s Solo Violin Sonata no.2

Read: Playfulness, humour and religion: character in Bach’s solo violin sonatas

Read: Bach Solo Violin Sonatas: At heart a fugue

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #3: Benjamin Baker on performing solo Bach

-

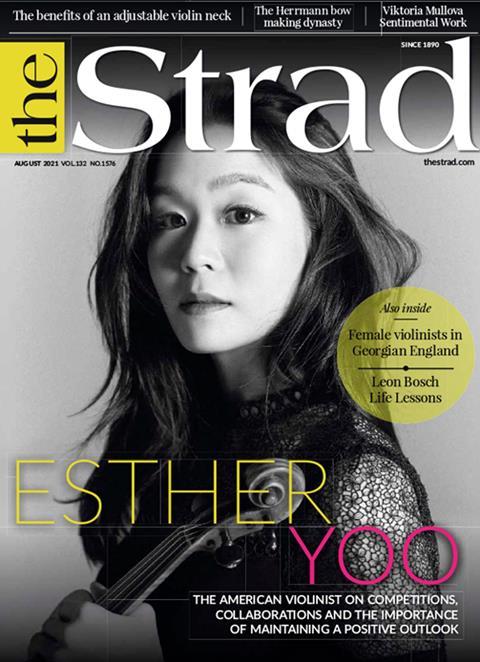

This article was published in the August 2021 Esther Yoo issue

The American violinist on competitions, collaborations and the importance of maintaining a positive outlook. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- American violinist Esther Yoo

- The benefits of an adjustable violin neck

- Bach’s Solo Violin Partitas

- The Herrmann bow making dynasty

- Female violinists in 18th-century England

- Making accurate arching templates

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet