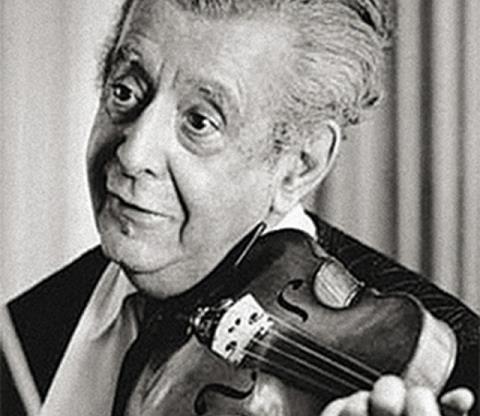

Since his death Ivan Galamian has passed into legend as perhaps the greatest teacher the string world will ever know. Barbara L. Sand asked some of his ex-pupils whether their former master really lived up to his reputation

Ivan Galamian arrived in the US in 1937, having grown up in Russia and subsequently emigrating to Paris. Over the next 40 years, until his death in 1981, Galamian became the most powerful and sought-after violin teacher in the country. Many of his students have certainly been successful: during those years the highly regarded Leventritt Competition was won by no fewer than seven Galamian students: Itzhak Perlman, Pinchas Zukerman, Betty Jean Hagen, Sergiu Luca, Arnold Steinhardt, David Nadien and Kyung-Wha Chung. Other students were winners of the Queen Elisabeth, Tchaikovsky, Carl Flesch and Wieniawski competitions - in fact all the international competitions of note. But although such students ensured that his reputation as a great pedagogue remained unchallenged, Galamian also made his name as a teacher who could produce excellent results from less talented material. Indeed, his teaching methods were envied and emulated throughout his career and, after his death, were perpetuated through the Meadowmount School of Music.

Upon arriving in the US, Galamian's Manhattan studio almost immediately became a mecca for gifted students. Word of mouth via both parents and and teachers produced a constant stream of young hopefuls, and even after Galamian was appointed to the faculties of both the Juilliard School and the Curtis Institute in the mid 1940s, most of his teaching continued to take place in his studio, In 1941 Galamian married Judith Johnson and in 1944 they established the Meadowmount School of Music in the Adirondack mountains, which was to become famous worldwide for its high standards.

David Nadien was one of a handful of violinists who lived with the Galamians while studying with the master. He later became concertmaster of the New York Philharmonic and held that post for some years before deciding to work as a freelance musician and teacher.

'The apartment [the Galamian's permanent home on West 73rd Street in Manhattan] had great long hallways and a lot of rooms,' recalls Nadien. 'Galamian had his studio in the front, and we - Helen Kwalwasser, Yura Osmolovsy and I - had rooms in the back where we practised three or four hours a day. It was a relaxed atmosphere and all of us had fun. Galamian had two beautiful boxer dogs that he was devoted to, and they were a big part of the household. At one time it seemed that somebody was stealing food from the fridge. Galamian stayed up in the dark in the kitchen one night to catch the guilty party. One of the boxers had actually figured out how to manipulate the handle and open the fridge door!

'Galamian was a good musician with excellent musical taste. The students who played best did not always do what he suggested, but if they sounded well he was wise enough to leave them alone. He taught by demonstration, and one had to use a grain of salt with some of the things he said. However, he gave me a general musical approach to understanding the repertoire, which I had not received from my previous teacher Adolfo Betti. Galamian stressed warmth and good sound and unquestionably deserves a major place in the history of violin teaching.'

Many of Galamian's students seem to have found him a more intimidating character than Nadien, perhaps because they did not live at such close quarters.

'His teaching method was Scare You to Death,' says Itzhak Perlman, 'You had better play it perfectly or else his eyes would glare down on you and make you feel like That's It! There was almost no room for give and take because he had a particular system that he applied to everybody. Some of his greatness lies in the fact that he could teach anybody, no matter how talented or untalented they were, to play the violin very well. Some would be more inspired, some would be better, obviously, but they would all be proficient at what they did when they studied with him.'

'I was nervous around Galamian when I was his student,' confirms Arnold Steinhardt, first violinist of the Guarneri Quartet. 'He didn't speak a lot during a lesson and hardly ever smiled. He never threatened or cajoled - he had enormous presence. His basic feeling was that anybody could become a fine violinist. The stage was already set in his studio, with photographs of Vieuxtemps and Corelli looking at you, He taught from 8am to 6pm seven days a week, and every lesson would last precisely 59 minutes - never more, never less. All Galamian's students were given two basic principles, which he delivered in a heavy Russian accent. One was 'More bow!' and the other was 'Play so that the last person in the last row of the hall can hear you.' Both excellent pieces of advice.

'Later after I had graduated, I came to know Galamian socially and found he could be both kind and funny. Sometimes we would play chess together at Meadowmount and he would like to have a glass of vodka with the game, 'One glass is good,' he would say; 'two is better; three is not enough.' When I was no longer a student he was very friendly.'

James Buswell, who teaches at the New England Conservatory of Music, is another artist who studied with Galamian. 'Not a day goes by that I don't talk about him as a teacher,' says Buswell. 'Once you have been under a master, it pervades all your own teaching.'

Buswell describes Galamian as a man with an analytical mind who tried to instill in students his profound philosophy of order. 'Galamian had a revolutionary technique for the bow arm, which was based on his knowledge of the laws of physics and anatomy,' he says, referring to the critical ability to project the violin sound. 'Galamian's burden was the acoustic survival of the stringed instrument. He taught his students how to make the violin soar over an orchestra.' Buswell adds: 'He had incredible patience. If he had confidence in you and felt you were on the right path, he was ready to repeat the same thing over and over'. He was a man of quiet determination who had a constant work ethic.'

'People always said Galamian could make a violinist out of a table,' says Peter Oundjian, ex-first violinist of the Tokyo Quartet and now a conductor, who studied with both Galamian and Dorothy DeLay. 'I think he could make anyone have a sound because he really had a method of position for the bow arm. But I remember one particular lesson in which I was having trouble with a passage in the Lalo Concerto. I played through the four études and the Bach I had been assigned and the whole Lalo, Galamian did not say anything, so I said to him: 'Mr Galamian, in this passage in the last movement of the Lalo I am really having difficulty. Can you tell me how I can make it better?' Galamian's response was to say, soberly, 'When you have played it 2,000 times it will be much easier.' Unfortunately, it's not true. Now I am older I think it is more important to find out what you are doing wrong than to play a piece 2,000 times and see if it gets easier.'

Dorothy DeLay, who subsequently wore the mantle of the world's most famous violin teacher, was herself a student of Galamian and later became his chief assistant. The two had a longstanding dispute over teaching methods in the early 1970s, but Delay continued to speak of Galamian with great respect. 'He came from southern Russia, from an Armenian family, and in those families the father's word is law,' she said. 'If anyone in the family disobeys, it is a powerful insult to the father. Galamian's background meant that he was a person for whom dignity was very important, and he felt that formalities, even with children, must be adhered to. So there was that cultural difference between us. He preferred to work in straightforward ways on technique. His area of expertise was the bow and he was excellent with it. His students all had big, healthy sounds - and they were beautifully organised.'

Galamian's teaching method has been summed up by Robin Stowell, editor of The Cambridge Companion to the Violin, as follows: '[It] embraces the best traditions of the Russian and French violin schools. For him, the key to technical proficiency is mental control over physical movement, but his is a flexible method with no rigid rules. More important is that the teacher promotes the maximum musical and technical development in each individual.'

This article was first published in The Strad's September 1997 issue

No comments yet