In this article from the October 2009 issue, Philip Kass untangles Rogeri, Rugeri and the last Amati in taking a closer look at a late 17th-century violin by the first

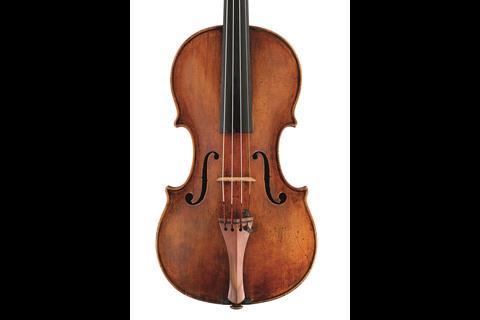

Maker: Rogeri, a native of Bologna whose name is often confused with that of the Cremonese violin making family Rugeri, worked in Nicolò Amati’s workshop in the early 1660s. He moved to Brescia in 1663 and established the Cremonese tradition in that city. This violin offers eloquent testimony to the similarities and potential for confusion between the work of Girolamo Amati II and Giovanni Battista Rogeri.

Girolamo Amati, who shared his name with his grandfather, would have just begun learning the craft during Rogeri’s tenure. He presided over the collapse of the Amati dynasty, and created far fewer instruments than his predecessors. He was thus virtually unknown to early scholars such as Cozio, who presumed the works of Amati to be those of Rogeri, unfortunately leading to label alterations, such as the one on this instrument.

Both makers had a number of distinctive traits in common: an outline with abbreviated corners and a flatness to the upper and lower edges; closely set vertical f-holes, which result in a broad, flat margin between the edges and f-holes; minimal scooping through the transition from pegbox to volutes; and generally shallow carving throughout the scroll. Yet there were also distinctive edges in the two makers’ styles that enable us to spot the differences between their instruments.

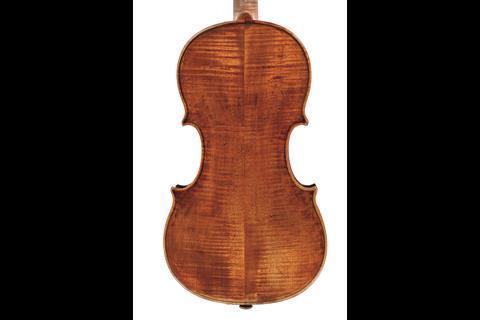

Style: The back wood of this violin, with its distinctive narrow curl, and the deep golden–orange varnish with dark ground, is characteristic of the Rogeri family. The longer corners with their delicate hooked tips, evidence of which has not been completely worn off over time, are also a classic Rogeri feature, as is the heavy, broad frontal profile of the scroll.

Rogeri’s f-holes tend to have narrower stems and larger and rounder holes than those of Girolamo Amati, the lower ones often tending to turn sharply inward. The abrupt flattening of the curve leading into the upper holes suggests more than a passing awareness of Jacob Stainer’s popularity.

History: Today this violin bears a facsimile of Girolamo Amati’s label dated 1699. When it was sold in 1938 it carried two certificates: one from Rudolph Wurlitzer, in which Jay C. Freeman called it a Girolamo Amati, and one from W.E. Hill & Sons, who called it a Rogeri of the 1670–80 period.

This instrument was Felix Galimir’s teaching violin, which he had acquired from his brother-in-law, Louis Krasner. He bequeathed it to the Curtis Institute of Music, where it remains today for the benefit of its students.

Photos: Christopher Germain

No comments yet