Marked forever by Paganini and nearly lost in the snow by Piatti, this 1717 cello by Pietro Giacomo Rogeri has had a colourful history. Article by John Dilworth from the July 2009 issue

The confusingly named Rugeri and Rogeri clans both made important and treasured contributions to the history of stringed instruments, and while both are rooted in the Cremonese tradition, there is apparently no connection between these families beyond the similarity of their names, and they diverged considerably as the 17th century drew to a close.

Any misunderstanding that might still exist is a result of the casual approach to spelling that prevailed during their lifetimes. Both families occasionally used the ‘u’ and a double ‘g’ on their printed labels, and scribes entered their names in state records in every conceivable combination. For clarity’s sake, Francesco Rugeri and his family were Cremonese through and through, and remained there all their working lives. Giovanni Battista Rogeri and his son Pietro Giacomo, the maker of the cello described here, worked mostly in Brescia.

Giovanni Battista Rogeri was actually born in Bologna in about 1642, but in 1661 and 1662 he appeared in the census returns of the Amati household as an apprentice to Nicolò Amati – incidentally, his name is given as both ‘Gio Batta Ruggieri’ and ‘Rugieri’ in these documents. He seems to have learnt quickly and worked well enough to have mastered his craft within those two years. By 1664 he had left Cremona and was married and settled in Brescia.

Within a year his marriage had produced a son, Pietro Giacomo, born on 12 March 1665. Pietro Giacomo was to become the heir to the business and although he married, he had no children, and when he died in 1724, the shop finally closed.

The cello is a particularly fine example of Rogeri’s craft

Pietro Giacomo’s making style is extremely elegant, to the extent that some authorities have implied that there is a hint of decadence in his extended corners and slender soundholes. In truth, both father and son were very able craftsmen who succeeded in developing the Amati model into something entirely personal and distinctive.

There are two immediately interesting points about their work. The first is the striking use of the very finest wood, despite the obvious shortcuts sometimes taken in the deployment of painted purfling and sometimes less-than-impressive varnish. The second is their prolific output of cellos, all made on a very personal model and of small size, completely distinct from the Cremonese standard of the time, of which the example illustrated is a particularly fine and typical one.

This cello, made in 1717, displays all the features mentioned above, and the most obvious is the superb quality of the maple used. The deep, broad and regular flame really is remarkable, and there seems to have been no shortage of such beautiful maple in the Rogeri shop. Brescia was then part of the Venetian republic and supplies of such dramatic timber would almost certainly have been imported from ports on the Dalmatian coast, across the Adriatic sea. Many Rogeri cellos bask in this spectacular flame, which runs throughout the back, ribs and scroll, all seemingly cut from one billet of timber for each instrument.

Particularly striking is the fact that the lower ribs are made from one piece, running from corner to corner. This must have been sawn from a board a good metre in length – considerably more than the back itself.

The arching of the back is full and rounded – in some cases, Rogeri’s instruments tend to have a rather square profile, but on this cello the shaping is particularly fine, with a substantial edge flute in the upper and lower bouts, but a strong rise from the purfling through the centre bouts. This gives the cello a very strong ‘heart’. The central bouts are crucial for generating a powerful tone, and this instrument is certainly designed with that in mind. While the lower bouts are comparable to that of Stradivari’s B form, the upper and middle bouts are much wider. The extra 15mm across the middle bouts provides a strong sounding board beneath the bridge, a characteristic of the great cellos of Montagnana and Guadagnini.

Piatti nearly lost this cello in Dublin when it slipped from the roof of his horse-drawn cab

The front also has a full, rounded arch, and is made from beautiful straight-grained quarter-cut spruce, of subtler but equally high-quality tonewood as the flashy maple used for the back, ribs and scroll. The grain is fine at the centre, opening out gradually towards the soundholes, then remaining a consistent, medium width to the flanks. Deep transverse gouge strokes can still be seen beneath the varnish in the upper half of the plate.

The soundholes are very characteristic of Rogeri. Laid on to the table in an upright position, but well placed for width and proportion, the arms are very slender – too narrow for a modern soundpost to fit through – and formed with quite a steep undercut on the inner edge.

The finial circles too are very small in diameter, and the fluting of the lower wing is flat; the wing has definitely been carved below the arched surface, but it does not have a strong channelled shape. The whole design and disposition of the f-holes seems aimed at keeping the central part of the soundboard as stiff and strong as possible.

The head is magnificent – a boldly enlarged version of his violin scrolls in design and execution. The pegbox is deep and full, but elegantly shaped from the Amati master template. The throat is quite open, and there are signs that the cutting of it encroached on the first turn of the spiral, which is slightly flattened, producing a rather oval form to the volute. The eye is quite small, and approached by a neat chamfer and a deep undercut on the last turn, which throws it into relief. The front face of the spiral is scored by transverse knife cuts, indicating the manner in which the flutings were carved, and the fluting flattens out and stops short in the approach to the throat. Cross-cut gouge marks carry through the rest of the fluting behind the pegbox.

The varnish is also typical. Comparable with the finest golden–brown Amati coatings, it has depth and radiance, despite an understated ochre-like pigmentation, which is not completely transparent, but interacts perfectly with the dazzling reflections in the wood beneath. It seems odd that on some instruments Rogeri reduced this varnish to a thin, rather dull layer and dispensed with purfling altogether, while still using up stocks of shimmering, flamed maple – all that can be said is that presumably the wood was then more easily acquired than time, money or even customers.

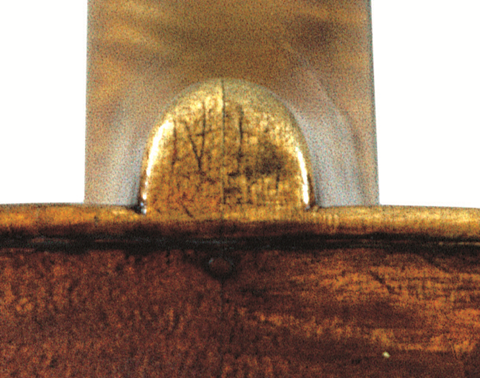

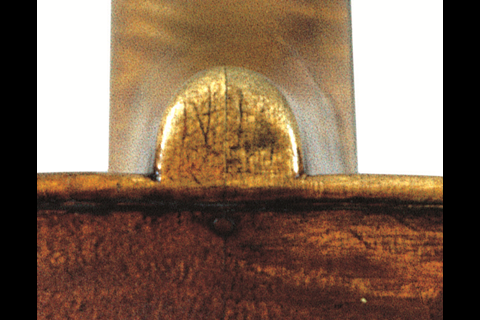

Nicolò Paganini scratched his initials on to the back button, before pawning it to pay off a gambling debt

This magnificent cello has a suitably colourful history. An 1898 issue of the Violin Times tells how Nicolò Paganini scratched his initials on to the back button, where the characters ‘NP’ can still be clearly seen, before pawning it to pay off a gambling debt. It was then bought from the pawnbroker for £30 by the Duke of Parma.

The Hills mention it specifically in their seminal book Antonio Stradivari, His Life and Work in their discussion of the evolution of Stradivari’s cello designs. They call it an ‘admiral form … of excellent dimensions … for many years used by Signor [Alfredo] Piatti as his solo cello’. According to the Violin Times, the Duke of Parma presented it to Piatti himself, and the great cellist nearly lost it in Dublin when it slipped from the roof of his horse-drawn cab.

Fortunately the streets were thickly covered with snow at the time and the cello was recovered unharmed in its case. From Piatti it passed to Muriel Handley Spicer of London and then to Gilberto Crepax, professor at the Milan Conservatoire and soloist of the Orchestra Toscanini.

Crepax died in 1970, and the instrument was acquired by Rocco Filippini, before it was passed to its present player, Italian soloist Enrico Dindo. It is now one of the many fine instruments managed by the Fondazione Pro Canale, under whose auspices it is currently on loan to Dindo.

But perhaps its most colourful – and unusual – role is as the hero of a cartoon. Gilberto Crepax’s son Guido gained notoriety in the 1970s as the author of popular cartoon books, one of which had this Pietro Giacomo Rogeri cello as its eponymous hero.

Celebrated in fact and fiction, this cello is a wonderful tribute to a sometimes overlooked luthier – the son of a more famous maker, working in a city celebrated more for a previous – and quite different – generation of makers, but quite able to stand up for himself as a remarkable craftsman and master cello builder.

This is an edited version of an article which first appeared in the July 2009 issue of The Strad, which also included a poster of the Rogeri Cello. To order a rolled copy of the poster, visit The Strad Shop

No comments yet