Prokofiev’s First Violin Concerto provided some early inspiration for the British violinist – as well as a crash course in some fast, efficient playing

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

I was 13 when I first heard Prokofiev’s Violin Concerto no.1. A friend had invited me to Abbey Road Studios to watch Maxim Vengerov record the concerto with the London Symphony Orchestra. At that time Vengerov was my idol; I’d sit in the front row of every concert watching the incredible passion and musical power of this 19-year-old as he performed so unbelievably well. He was the benchmark for everything I was aspiring towards, and after hearing him perform the concerto I began to look for every recording of it that I could find. I became slightly obsessed with a live recording from 1960, made by Nathan Milstein with the Orchestre de la Suisse Romande. I was a bit scared by it: he played the second movement so fast but so accurately, and with incredible spirit. I thought he could barely be human! So that piece became bound up with my own desire to be a great violinist.

I didn’t really practise the concerto myself until I was 19. The Royal Scottish National Orchestra invited me to perform as a soloist and I suggested Prokofiev’s First, although I couldn’t yet play it by then. I tend to need a reason to learn something before I start properly practising it, and I was desperate for the chance to learn this piece. The first movement has an extraterrestrial quality – some of the most ethereal, otherworldly violin lines I can imagine. When I’m given a new fiddle to try out, I always play the first few lines of this movement for a thorough road-test. Then the second subject has a kind of spiky, naughty character that allows you to bring in all the off-rhythms.

Listen: The Strad Podcast Episode #15: Jack Liebeck on Ysaÿe Sonatas

Watch: Jack Liebeck plays Stuart Hancock concerto cadenza

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

I repeatedly said to myself, ‘If it’s possible for those other people, it must be possible for me too!’ The way it’s written, Prokofiev’s smooth lines are not very comfortable, with lots of bow changes on the off-beats, and if they’re done badly they can sound very angular and syncopated. I had to find a way to cushion my movements to make it come across the right way.

The second movement has passages that are verging on unplayable. It has a dangerous, frenetic character made up of short bursts, and the soloist needs to move around the instrument quickly and nimbly. Everything has to be about efficiency, and the audience mustn’t ever know – it’s our job to make it look easy. Performing the concerto undoubtedly improved my technical knowledge.

Finally, the third movement is a delicate, elusive delight. I love its balletic characteristics, and when I’m playing it I imagine trying to inspire someone to choreograph it; for instance, the opening is made up of little footsteps, as if a dancer is tentatively coming on stage. So much of what we do is based on movement, and Prokofiev’s sound world is ideally suited to choreography – it’s one step away from movie music. For me, the concerto should always make my spine tingle. If it doesn’t, it’s not a good performance.

I’ve probably taught the concerto more than I’ve played it myself. Teaching it has meant I’ve learnt even more about the underlying structure and inner workings of the piece; it’s also perfect for me as my students will attest, I’m constantly dancing, singing and gesturing in the classroom. What we do is never just about the sound. I also tell them to think about Prokofiev’s long lines. I tell them to listen to recordings of Heifetz, who knows right from the start where the last note’s going to be placed, almost to a point where it sounds like he’s running towards it.

I really would love to record this concerto one day. Over the years I’ve met many people who are obsessed with this piece, and it always turns out I have a similar musical outlook to them.

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

Watch: David and Igor Oistrakh perform Prokofiev Sonata for two violins

Read: Sentimental Work: Jennifer Pike

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

-

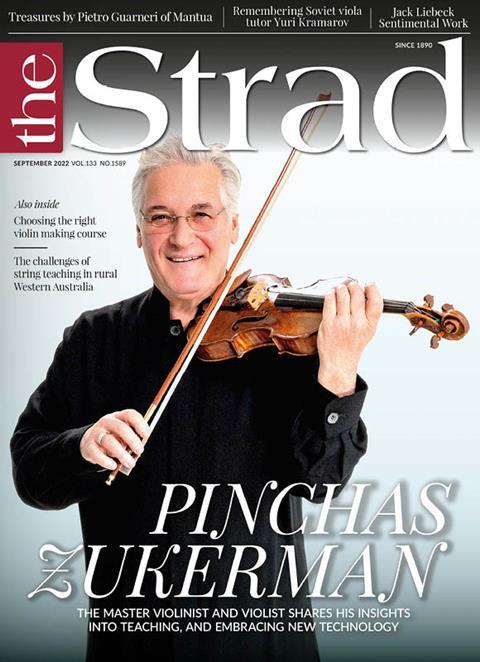

This article was published in the September 2022 Pinchas Zukerman issue.

The veteran violinist and violist tells Pauline Harding his views on everything from his new masterclass series to the role of technology in string teaching . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Pinchas Zukerman

- International Lutherie Schools

- Newark School of Violin Making

- Strings in regional Western Australia

- Villiers Quartet Session Report

- Pietro Guarneri of Mantua

Read more playing content here

-

No comments yet