Debussy’s Sonata for flute, viola and harp is just one of many works written for that combination, and is a prime example of how loosening fixed traditions can open new and exciting sound worlds, writes Toby Deller

I sometimes get the nagging feeling, listening to piano trios, that there’s something missing. Something in the middle of the texture, perhaps? An emollient voice tempering the soloistic onslaught? Or am I simply a viola player envious because of my instrument’s absence from such a popular chamber music genre?

If the viola has suffered from being overshadowed by the violin and cello, Claude Debussy is one composer who helped it find an identity elsewhere. His Sonata for flute, viola and harp, completed in the autumn of 1915, may not have been the first time these instruments made a threesome together – there is a 1905 Terzettino by Théodore Dubois, the director of the Paris Conservatoire who warned students off attending the premiere of Debussy’s Pelléas et Mélisande. And Arnold Bax almost certainly wrote his Elegiac Trio of 1916 at around the same time, unaware of Debussy’s Sonata, which the composer himself only got to hear in December 1916. But it was surely Debussy’s renown that triggered the proliferation of works for this line-up – easily enough repertoire to keep a regular ensemble going.

They include Adieu by Darius Milhaud, viola player in the performance that Debussy attended, although he waited until 1964 before writing it. Their compatriot Maurice Duruflé was one of the first to follow Debussy’s footsteps in 1928 with a Prélude, Récitatif et Variations. There are examples from this century, including pieces by Libby Larsen, Per Nørgård and Anna Clyne; before them came many others by composers as stylistically diverse as Harald Genzmer, Tōru Takemitsu and Franco Donatoni. And then there are works with additional orchestra (Marga Richter), narrator (Sofia Gubaidulina) or vocalist (such as the Milhaud).

Whether Debussy expected the trio line-up to endure is a matter of speculation. He was probably just curious about the possibilities of an unfamiliar instrumental combination. The Sonata is one of a series of six he devised for various groupings of individual instruments, all of them gathering for the last in the sequence. He died before getting as far as that or the planned sonatas for oboe, horn and harpsichord, and for trumpet, clarinet, bassoon and piano. The only others he completed were the duo sonatas with piano for violin and cello – the instruments that comprise the piano trio.

Read: 9 tips on playing the Ravel and Debussy quartets

Read: Opinion: Defining relevance

Read: Opinion: Original and the best?

Although the instrumentation of the harp trio doubles the piano trio (flute/violin, viola/cello, harp/piano), it is a double from another place. Debussy reveals a sound world evoking the masques and bergamasques of Paul Verlaine’s poem Clair de lune, or harks back to an imagined music of the antiquity beloved of certain symbolist poets – of Orpheus and his lyre, Apollo and his flute. Indeed, it could easily be a ballet in which three characters happen upon each other in some idyllic setting (the first movement is entitled Pastorale) along the lines of the Prélude à l’après-midi d’un faune.

Certainly, the music is a world away from that of Dubois’s lovely, Gounod-like piece, and from the perfume of the salon or middle European musical gathering that the piano trio so obviously calls home. It is also a new environment for the viola, emancipated from the compulsion to compete with its fellow members of the string family, through fellowship with new-found friends. So, there is a message here about the importance of enriching one’s musicianship by looking beyond a familiar entourage: what can a viola player learn about phrasing from playing with a flautist? Or about projection and balance from playing with a harp rather than a piano?

But there are wider musical messages, too, that might be particularly relevant as we try to reconstruct our somewhat shattered musical world. We might consider how the adherence to fixed traditions of composition and performance, while undoubtedly generating an ever-expanding repertoire of expressive depth, runs the risk of being exclusive. Of leaving doors unopened to whole new musical worlds, and whole new undreamt ways of being musical.

-

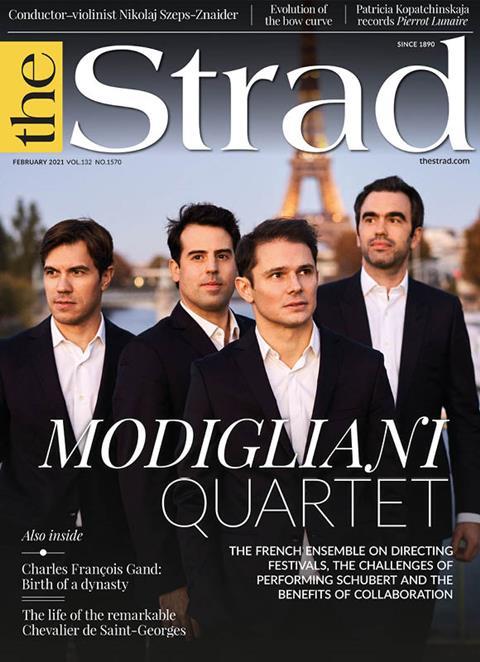

This article was published in the February 2021 Modigliani Quartet issue

The French ensemble on directing festivals, the challenges of performing Schubert and the benefits of collaboration. Explore all the articles in this issue . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French ensemble the Modigliani Quartet

- Charles-François Gand: birth of a dynasty

- Conductor-violinist Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider

- Patricia Kopatchinskaja records Pierrot Lunaire

- Evolution of the bow curve

- The life of the remarkable Chevalier de Saint-Georges

Read more playing content here

No comments yet