Music students have the confidence to engage with silence, whether before, during or immediately after a piece, writes Naomi Yandell

Casting my mind back to my earliest days as a young student I clearly recall my teacher telling me that I wasn’t counting my rests fully. Somehow they seemed interminable and even a bit scary; I was cutting them short to bring them to a close and to move into the safety of sound.

Observing my students, especially the youngest, I sense that they must often feel as I did. They have a propensity to launch headlong into a scale or piece without a moment’s thought, to rush through double bar-lines or to worry at a tricky passage just as we are preparing to start the lesson.

As teachers we need to help our students to feel comfortable with silence and to harness it with confidence. After all, it encases, punctuates and shapes everything that musicians do. To do this effectively we need to incorporate the concept of silence into our teaching and practice regimes from the beginning, so that focused use of silence becomes the default position in a performance situation. Today, this is arguably even more difficult to do than in the past because silence has become a rare commodity, often with negative connotations.

Just as tennis players focus their thoughts before serving (and silence is called), so it is useful for students to take time to think before beginning to play, whether in practice or performance situations. For my youngest students I talk about a ‘get-ready moment’. For the little ones especially, I supply concrete ideas for where their thoughts should be in that period of silence.

Somehow rests seemed interminable and even a bit scary

My ideas might include imagining a suitable pulse, preparing the bow to play on a particular string, or thinking about a good left-hand shape. I might also ask them to use their thinking voices to sing the last few bars of the piece they are about to play to help them capture the mood or to recall the story of the piece (which I will have asked them to imagine). As students get older, my approach becomes less prescriptive. Instead, to ensure that they have considered their get-ready moments, I ask them what they will be thinking about as they prepare to start, and then I make tweaks or suggestions as necessary.

The use of silence within phrasing is also important – and it’s worth taking time to ensure that students are in touch with the ebb and flow of the music. I find it useful to play alternate phrases with them. I don’t tell them where phrases begin or end but let them discover this for themselves. It’s rare to encounter a student who can’t sense the necessary hiatuses demanded by the music.

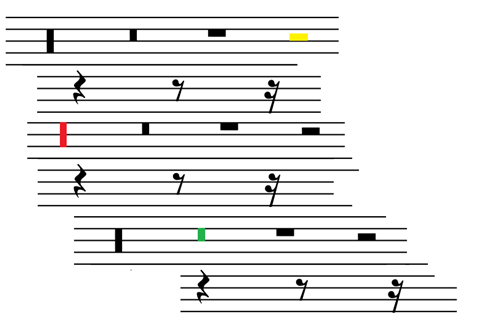

Rests, too, need to be considered seriously: they are often overlooked in the learning of a piece – especially (though not exclusively) within the context of ensemble pieces, where the student might not initially appreciate that their part is only one element of the whole. It is important to teach an understanding of the function of a rest within a piece. Why has the composer used a rest at that point? Is it there to introduce a melody or to act as an echo? Or does it allow space for the voicing of a contrasting idea?

Sometimes composers write rests at the ends of pieces, a detail often overlooked by young students in their haste to finish the piece that they’re playing and thereby to tick it off their to-do list. Musical maturity comes in this regard when students have the confidence to engage with the silence after the last phrase of a piece – and to hold the atmosphere they have created. As they say, silence is golden.

No comments yet