Philip Kass reviews the long-awaited volume on the most important bow maker who ever lived

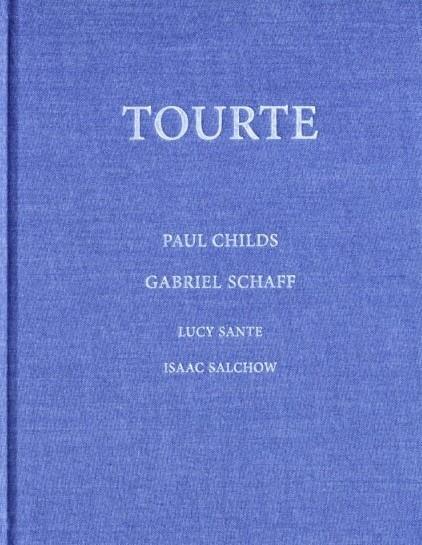

Tourte

Paul Childs, Gabriel Schaff, Lucy Sante, Isaac Salchow

273PP ISBN 9780965178822

Magic Bow Publications $300

My library is full of books about individual violin makers, monographs on many of the great masters of past centuries. When it comes to the greatest bow makers, though, the list is short: Stewart Pollens’s collaboration with Henryk Kaston on the life and work of François Tourte and Paul Childs’s monographs on the Peccatte family and Persoit. The significance of his writings on these last two families has begged the question of when he might write something similar about Tourte, the single most significant bow maker in the history of the craft. The answer is ‘now’, for this long-awaited volume is at last here.

Over the past few decades, the expectations for new books on instruments and bows have changed significantly; one needs not just good photos of good examples, but also a detailed explanation of the life of the artist and his times, as well as a detailed explanation of what the characteristics of workmanship are and how they develop over time.

Considering Tourte’s importance, it is understandable that one might weigh carefully how to write the biography, and how to analyse the work, and so not rush into something hastily. This has proven a wise approach on a variety of levels. New discoveries in fine bows that can be specifically dated to the year have changed our understanding on how we date and appreciate Tourte’s work, and the nagging problems of detailing an individual’s life, given the destructions and incomplete reconstitution of archives during the French Revolution and the Paris Comune, mean that there is always the chance that one more document might turn up that completely changes the explanation. But nevertheless, no one interested in bows should pass by this book, and anyway, one can never have too many reference photographs of fine Tourtes. Following the biographies are photo reproductions of the significant examples discovered, an act of transparency that will be deeply appreciated by the generations of Tourte scholars to come.

Paul Childs shares the authorship of this book with three others; indeed, this could well be how such books are written in the future, as the requirements and expectations on the subject grow ever more complex. Since they take more time, they now require more authors. The reader who fails to comprehend the lessons that are taught in such books leaves with a superficial understanding of the work at best. A lot of readers will be tempted to jump straight to the photographs, but it is important to read all the essays, because without doing so one can seriously misunderstand what is being presented.

Read: How did Giovanni Battista Viotti influence the evolution of the Tourte bow?

Read: ‘The great artistry of history’s most important bow maker’ - François Xavier Tourte

The four sections cover the history of France during the years of Tourte’s life; a detailed biography of Tourte and his family; and two separate analyses about his working methods. This last section contains excellent photographs of over 90 fine bows, mostly by François Tourte and his brother Nicolas Léonard, but a few by contemporaries that shed light on stylistic matters.

The first author is Lucy Sante, whose essay on the cultural, social and political history of France is a delight, giving a valuable overview of those times as well as an understanding of why France’s history progressed as it did. While it represents just a thumbnail sketch on a complicated nation’s history, it provides all the most critical facts, and does so in chronological order which the reader can then tie back to the Tourte family and their lives.

There follows a biography of Tourte and his family, written by Gabriel Schaff. He has followed the paper trail and made an excellent explanation of their lives and activities. However, this includes describing the various ways in which an event might have played out and other ways it could be interpreted. As mentioned, a significant number of documents are at least for the moment unavailable. As Schaff repeatedly points out, there are gaps in our information, so while we understand events a certain way, the rediscovered records could fundamentally change some of our conclusions. Even so, the life stories he recounts are fascinating. François’s profession is linked to the great musicians who both promoted him and encouraged him, and while it is disappointing not to find evidence of the supposed connection between Tourte and Viotti, there are plenty of others to fill that gap.

Since Paul shared with Isaac Salchow the expertise in selecting the bows for illustration, they have both written commentaries and discussions on the work of the Tourtes. Paul’s is the more detailed and succinct, a thorough explanation of method, style and aesthetics, and while the discovery of related documents pushes the entire timeline backwards, it does not change the overall explanation. He also deals with the subject of expertise on the bows of Nicolas Léonard, the questions regarding brands, and the lingering questions regarding the mysterious ‘Tourte T’, all of which is vital. Isaac’s essay, which follows the photographs, is shorter but deals much more with methodology, concentrating on carving, finishing, and on Tourte’s metalwork, which Paul dealt with only in passing.

In between are the photos of bows as well as close-up details of brands, toolmarks, head models and finishes, heel and head mortises, frog finishes and metalwork. Again, it must be stressed that Paul and Isaac’s texts must be read thoroughly as otherwise the reader will miss a great deal of the subtleties in the bows. Both essays make specific references to matters of workmanship in which they direct the reader’s attention back to specific bows. Many will find themselves turning back and forth between photos and discussions, trying to bring those lessons to clarity.

While this might not be the last word on Tourte, we are that much richer for this book’s arrival, and the serious student of fine French bows should treat this as their ultimate reference for the foreseeable future.

PHILIP KASS

No comments yet