Tully Potter reviews a biography of a renowned violinist who fell foul of Maoist China

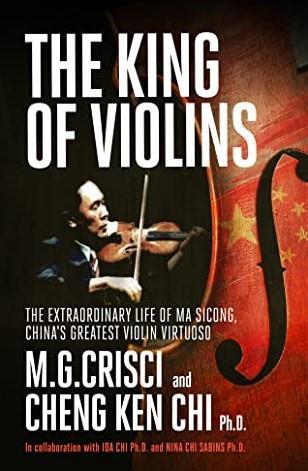

The King of Violins: The Extraordinary Life of Ma Sicong, China’s Greatest Violin Virtuoso

M.G. Crisci, Cheng Ken Chi

302PP ISBN 9781456635343

Orca Publishing £24.95

This book certainly describes an extraordinary life, but it does so in an extraordinary way, of which more later. It tells the story of a Parisian-trained violinist and composer who rose to the very highest rank in Chinese culture, only to have his career snatched away by Mao Zedong’s iniquitous Cultural Revolution in 1966.

Born in Haifeng in 1912, Ma Sicong (aka Ma Szu-ts’ung, Sitson Ma or Ma Sitson in English) was the son of Ma Yuhang, a leading figure in the revolutionary movement. He did not play the violin until he was eleven, but followed a brother to Paris and after some setbacks, entered the Conservatoire in 1928. His teachers included Jules Boucherit. He also studied composition.

Ma married a pianist and together they weathered one of the stormiest periods in China’s history, giving concerts up and down the country. Ma developed a distinguished teaching career in parallel with his performing and composing, founding a private music school: he was also on the faculty of Nanjing and Guangdong universities.

First in Tianjin and then in Beijing, Ma established the Central Conservatory of Music when the Communists took over. He was on good terms with prime minister Zhou Enlai, a man of some culture, but Chairman Mao referred to him, to his face, as ‘the expensive one who studied in France’ and asked him: ‘Does your art serve the masses?’

As violinist and administrator, Ma seems to have been the most prominent exponent of western music, but as a composer he straddled both East and West. When the Red Guards began running amok in June 1966, he was regularly humiliated, imprisoned in a cowshed and badly beaten up in public.

With his wife and two daughters, he managed to escape to Hong Kong and thence to the US, where after the first flurry of publicity – his defection was useful to the White House as a means of embarrassing Mao – he lived a fairly low-key life. His 1943 Violin Concerto was premiered in Philadelphia by his brother Ma Sihong and he himself gave the odd concert. He was much appreciated on visits to Taiwan and toured Europe with his wife in 1985 but never returned to China. He died in 1987.

It is difficult to assess Ma as a musician. I have heard only a tiny snatch of his playing on YouTube, which indicates a persuasive fiddler. The notices he received for two New York appearances suggest that he was stronger when playing his own pieces than when essaying western works. His huge corpus of music has been revived and recorded in China, where he is no longer considered a traitor.

The authors have made the very questionable decision to tell Ma’s story in the first person. For me, a biographical subject’s quotations are sacrosanct. Has Ma’s son-in-law Cheng Ken Chi memorised pages upon pages, chapters upon chapters, of Ma’s conversation? Somehow I doubt it. The long Wikipedia entry on Ma says that he wrote an autobiography in 1937, so that book may have been a source for the early life. But the method reaches bathetic depths when Ma describes his own death and its aftermath!

The writing is banal, the editing is often poor, the photographs are badly reproduced, there is no index and the entire production reeks of cheapness. Ma Sicong surely deserved better, and for many of the facts of his life, which are omitted here, you are better off with Wikipedia.

TULLY POTTER

No comments yet