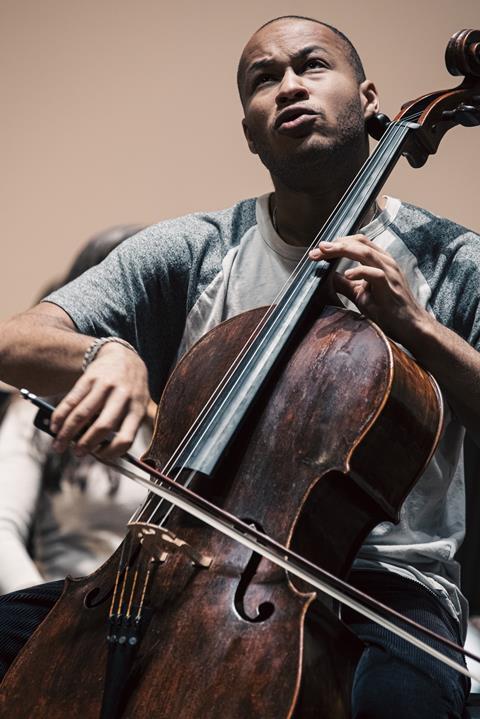

The British cellist speaks to The Strad about his deeply personal new album, the influence of Rostropovich and the emotional extremes that keep him returning to this music.

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Just released on Decca Classics, Sheku Kanneh-Mason’s Shostakovich & Britten brings together three works intimately tied to the towering legacy of Mstislav Rostropovich: Shostakovich’s Second Cello Concerto and his early Sonata in D minor from 1934, as well as the Cello Sonata Britten composed in 1961 – one of a remarkable harvest of pieces inspired by his friendship with Rostropovich.

It’s a deeply personal programme for the cellist, whose long-standing affinity for Shostakovich began with the First Concerto – the piece that launched his international career at the 2016 BBC Young Musician competition. On his new album, Kanneh-Mason turns to the lesser-known Second, a brooding, elliptical work written for Rostropovich in 1966, and pairs it with two sonatas that reveal contrasting facets of 20th-century chamber writing.

Recorded with conductor John Wilson and the Sinfonia of London, as well as pianist and sister Isata Kanneh-Mason, the album is both homage and discovery. The chamber works were captured at Snape Maltings, the concert hall esstablished by Britten and a site steeped in artistic history.

In this conversation with US correspondent Thomas May, Kanneh-Mason reflects on his connection to this repertoire, the influence of Rostropovich and why the extremes of this music continue to draw him in.

Your new album centres around Shostakovich’s Second Concerto – a deeply complex and often enigmatic work. What drew you to it?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: I find it endlessly challenging on many levels. The piece demands a very precise intensity of sound. You need to sustain that throughout in both the long-term shapes and the fine details.

I thought a lot about tempo and tempo relationships. The work can feel episodic, especially in the final movement, with many contrasting themes. I try to find the tension and cohesion between them through alignments in the rhythm and the tempo.

You’ve described feeling a very personal connection to this concerto.

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: Yes, absolutely. I remember the first time I heard the piece – it was a video of Rostropovich on YouTube. Of course I already knew the First Concerto and had been in love with Shostakovich’s symphonies for a long time. Hearing the Second was deeply moving, but also a little bit confusing. It left me with lots of questions. I became fascinated and wanted to explore it further.

It was quite an intense process to prepare as a piece, because the mood is sometimes very dark and pessimistic, with lots of thoughts about death. Spending time inside that world had an emotional effect, but it was also an intense and fascinating experience.

Alongside the Shostakovich Concerto you include his early Cello Sonata as well as the Cello Sonata of Benjamin Britten. What’s the idea behind your programming?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: The Britten Sonata, Shostakovich’s Sonata, and the Second Concerto all have connections to Rostropovich – who’s been a huge inspiration to me. I admire him and grew up listening to him a lot. I’m grateful to Rostropovich for convincing Britten, through their friendship, to write such wonderful music for the cello. Although Shostakovich’s sonata wasn’t originally written for him, Rostropovich recorded each of these sonatas with their composers. So there’s a wonderful connection between all three of them.

I’m grateful to Rostropovich for convincing Britten, through their friendship, to write such wonderful music for the cello

What excites you about the Britten?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: It’s structured in five movements, more like a suite than a traditional sonata, and each one is a specific character piece that explores different aspects of writing for cello and piano. The third movement, the Elegia, is for me the emotional heart of the piece. It traces the stages of grief in such an eloquent way. The outer movements are quirkier, more humorous.

What is it about Rostropovich’s playing that speaks to you so strongly?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: There’s always a deep and intense, fiery core to the sound – across all the dynamic levels. Even when he’s playing pianissimo, there’s a fizzing intensity, just as much as when he’s playing urgently extroverted passages. I’m so drawn to that commitment to each note and how to communicate it – and the sense that he’s playing a larger instrument than the cello. He’s able to sound orchestral and also to push its singing quality to its limits. It comes from having such a strong imagination combined with his technical facility, which makes his playing quite explosive at times.

What was it like recording the sonatas at the historic Snape Maltings Concert Hall founded by Britten, where he and Rostropovich recorded his sonata in 1968?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: I was very keen to record these sonatas there exactly because of this connection. The concert hall at Snape Maltings is also one of my favourite concert venues. It has an incredible acoustic that is sensitive to the detail in the music and allows the sound to develop in the space. It’s a special place to visit, because the countryside surrounding it is quite flat, so you can get the sense of an expanse, a feeling of space, which I think is great for creativity. People like Britten and Rostropovich thrived in that environment, and lots of great music was created there.

You recorded the chamber works with your sister, Isata Kanneh-Mason. How does that partnership shape the interpretation?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: We learnt both sonatas together from the beginning as a duo, not individually and then coming together with what we knew. That gave us a unified understanding of the music, which makes it very freeing. We can explore some of the extreme qualities of these pieces.

In both sonatas – in the Britten in particular – there are so many intelligently written interactions and shifting dialogues between the cello and piano. It’s like testing how far you can stretch the elastic band – seeing how responsive you can be to each other. That closeness reflects the music itself, which is about Britten and Rostropovich’s friendship. So it feels right to play it with someone close to me.

What makes this repertoire resonate on such a deep level for you?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: Because I’ve lived with it for a long time. I’ve thought about it deeply, played it often, and returned to it with new ideas. It feels like I’m slowly uncovering more and more of what’s inside the music – and that’s very satisfying. Performing Shostakovich especially feels like music I can lose myself in and learn things I enjoy finding on the instrument.

You recorded this on your Matteo Gofriller cello. What does the instrument bring to this music?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: It’s an incredible instrument – rich and dark, with a very soulful and individual voice, which is great for the music. It can be very powerful when it comes to playing concertos. It gives me support across its range, so I can be quite flexible with the sound. It helps me find specific colours or nuances I want very quickly.

Alongside all your musical activity, you’ve also just published two books – your memoir, The Power of Music: How Music Connects Us All, and a children’s picture book titled Little Sheku and the Animal Orchestra.

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: They were both quite enjoyable in different ways. The memoir grew out of a desire to gather my thoughts – conversations I’ve had with myself or with others – and put them into one place, crafting what I want to say in detail. It’s actually similar to practising the cello in terms of the mechanics, of constantly repeating questions to find the perfect way to express my thoughts.

The children’s book is quite different, of course, because I wanted to create a character I hope will inspire young readers, especially through music. That was the guiding idea.

What’s next for you?

Sheku Kanneh-Mason: Performing, of course, and lots of new music. I’ve been playing with my sister a lot. We’re working on a duo written for Isata and me by Natalie Klouda, and I’m also learning the Solo Cello Suite she wrote for a friend of mine – it’s on my music stand right now. Edmund Finnis, who’s a wonderful British composer, has written a cello concerto for me, which premieres in November in Los Angeles. That’s something I’m really looking forward to.

Sheku Kanneh-Mason’s album Shostakovich & Britten is released on 9 May 2025 on Decca Classics.

Read: Cellist Sheku Kanneh-Mason takes up NY Phil residency

Listen: The Strad Podcast: Sheku and Isata Kanneh-Mason on sibling collaboration

Read: Concert review: Sheku Kanneh-Mason (cello) Sinfonia of London/John Wilson

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet