Composer Andrew Chen discusses four experimental techniques for strings ahead of the premiere of his new work Ilk, to be performed by the Gould Piano Trio at Cheltenham Music Festival

Full disclosure: I’m a composer. I don’t really belong here. I can’t play a stringed instrument to save my life. But that simple (and perhaps tragic) fact hasn’t made me love listening to music for strings any less, and, in a way, it’s made me appreciate even more the finesse, control, and sheer mettle that one needs in order to master such an instrument.

I say this because strings have been front and centre of my mind in the recent past. Earlier this year I was commissioned by the Royal Philharmonic Society to write a new work for the Gould Piano Trio, to be premiered at Cheltenham Music Festival 2022. The ensemble line-up (violin, violoncello, and piano) is one I already knew quite well from the repertoire, but had never attempted to write for myself – and so the question of what exactly I should write became quite a conundrum.

Granted – as you might expect – I do really enjoy experimental sounds, and writing music that taps into the unknown, the unexplored, and the sometimes-just-plain-wacky. But, at the same time, I’m a big believer that some of the most powerful moments of musical communication come from writing that allows for detectable subtlety and nuance. Think of your favourite soloist, and those moments of pure magic that they can create through variations within just one simple technique – like Janine Jansen’s vivid, lush vibrato in her Introduction et Rondo-Capriccioso, or Gil Shaham’s glissandi in his Butterfly Lovers’ Concerto. Techniques, standard, extended, or any kind, are not simply just things to themselves but can also be doorways into myriad strands of expressive potential.

So, that’s what I wanted to do – find things that balanced the ‘new’ with this kind of communicative flexibility. You can find below just a few techniques that fulfilled the brief, and had the opportunity to shine within my own new piece – and, maybe, too, they could be a source of inspiration for you, in your own playing, improvising, composing, and music-making overall. Try them out!

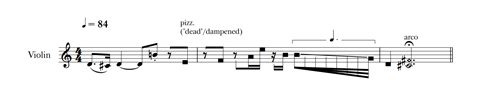

1. ‘Damped’ sounds – pizzicato

Many composers love to impart an almost-percussive sense of rhythmic drive and momentum into their works, not only as a way to anchor a piece but also to engage and draw in a listener. A good example is Schubert’s Death and the Maiden – replete with accented, unison motifs and an often-incessant semiquaver pulse. But we can take the ‘percussion’ idea more literally too, with a bit of inspiration from the popular stylings of the guitar and ‘palm muting’ – in an identical way we can use our left hand to dampen and deaden the strings so that our pizzicato becomes a stark, rounded thud, full of character and intrigue – and there’s still a lot of room to play around with the pitch, too, creating all kinds of contours and journeys within just the one kind of sound.

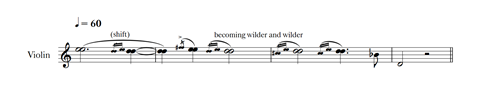

2. Varied, melodic shifts

Often, for string players, left-hand shifts up and down the fingerboard are thought of as a kind of annoyingly-finicky-but-essential part of legato playing; they’re seen as a kind of connective thread between notes, rather than a thing themselves to play around with. However, this isn’t the case universally, and for many, variations in the speed of shift, use of the bow hand, and even intonational stability, can be a great source of musical interest. In my piece for the Gould Trio, Ilk, I take it a step further by having these melodic string shifts occur within unison double stops, amplifying the presence of the effect. Check it out below:

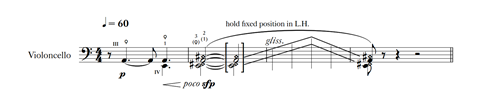

3. Artificial harmonics with ‘locked’ left hand

You might know this from George Crumb’s Vox Balanae, as the ‘seagull effect’ – where we physically hold the same left-hand position and slide up and down the fingerboard, without a care for the specific harmonics that might come out. Again, we can take the technique a step further, though, beyond just a momentary effect, by performing it across multiple strings at the same time.

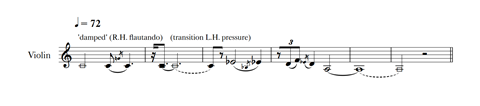

4. ‘Damped’ sounds – bowed

Left-hand dampening is not only something to use percussively but also in bowed contexts. If we use the same ‘damped’ technique as above, and then bow flautando (controlling dynamics by bow speed only, not pressure), we can create ghostly, whispering, wind-like noises, with a hint of the detectable pitch. I think it’s beautiful unto itself – but we can actually find all kinds of layers of translucency by varying up the left-hand pressure itself, and creating transitions between ‘damped’ and full-bodied sounds.

These are all fantastic techniques to play around with, no matter how experienced you are as a composer or improviser – I’d wholeheartedly recommend again you try them out and see what you come up with!

Recordings by Ella Ronson (violin) and Abby Lorimer (cello)

The Gould Piano Trio will perform Andrew Chen’s new work ‘Ilk’ on Saturday 9 July 2022 at the Cheltenham Music Festival. For more information, click here.

No comments yet