This masterwork is often treated as a party piece, but there is much more to it than that. Understanding harmony, history and opera is vital in performing it, says Maxim Vengerov, in this article from February 2007

The period in which Mozart wrote the Sinfonia concertante in E flat major, 1779–80, was an exciting one for him. Fresh from writing the five violin concertos he was starting to break through as an opera composer – Idomeneo was first performed in 1781. He had visited Mannheim in 1778, and found there one of the best orchestras in Europe, 50 players strong and able to play from the smallest pianissimo to the most gigantic fortissimo. He was stunned, and inspired.

Meanwhile, Baroque was being replaced by Classical and composers were looking for different forms: the concerto grosso was outdated. J.C. Bach and Haydn were experimenting with ‘symphonies concertantes’, symphonies that featured soloists but weren’t proper concertos. When Mozart discovered this, he decided to try his luck with the form.

It was also a very emotionally turbulent time for Mozart. He had been romantically linked with the brilliant singer Aloysia Weber, who inspired many of his concert arias, but the relationship had just ended. Then in July 1778 his mother died.

So the piece is romantic, imbued with loving feeling, but it’s also tragic and dark. It is often treated as a get-together piece, but it is the very serious statement of a composer trying something new, crossing over from Baroque to Classical. It is very important to know these factors before starting to work on this piece.

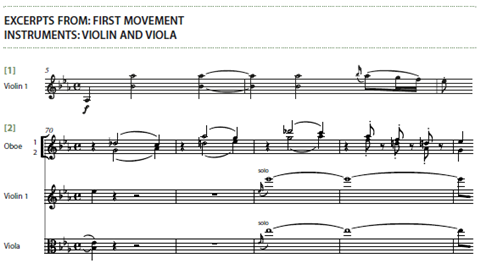

The first movement does not start with an introduction to the soloists’ entrance, as with the other concertos, but it evolves like an overture (example 1). The orchestral instruments come in discreetly, almost imperceptibly. The movement is based on a four-note sequence that first occurs in bar six of the first violin part:B flat–A flat–G–F (and various transformations). This later occurs in bar 17 (first violins), from bar 66 (oboes and first violins), bar 123 (solo viola) and elsewhere, and this singing line must always be heard.

We must always sing Mozart as much as possible, for example in the soloists’ entrance in bar 72 (example 2). This entrance isn’t, ‘Here we are, this is our solo.’ Until bar 126, when the orchestra takes an accompanying role, all the players are in partnership, as in a symphony. The soloists must come in very discreetly, so as not to disturb the oboe line, which can stand alone without the soloists. The wonderful thing about the Sinfonia concertante is that if you exclude the soloists it still sounds good. The solo parts only complement: they don’t overwhelm. The grace note should be on the beat and I would not take two bows for the long note – we should keep the original bowing. Come in with a subtle sound and less vibrato.You have to blend with all the other instruments. Use less vibrato, depending on the acoustic and the vibrato of the oboes. Make a tiny bit of a crescendo towards the end of the bar because the phrase continues into bar 74.

The orchestral line that moves between the oboes in bar 79 and the second violins in bar 80 is as important as the solo line – it is not an accompaniment (example 3). So the solo violin has to fit against what is already there. By itself, it’s only a descending line – nothing more. When Mozart writes dots over quavers, as here, they should have some length and not be too short – otherwise he would have used a dagger notation. He was very particular about his signs.

In bar 88 don’t crescendo too much, otherwise the horns’ theme will not be heard (example 4). This is quite melodic, so connect with the smooth horn parts. In this piece it is very important to be connected through colour and rhythm with the instruments that are supporting us.

Bars 90–93 in the orchestra create a change of scene – they’re very operatic (example 5). This is now C minor, which is used as the tragic tonality in the work – for example, the second movement is in C minor. The solo violin part in bar 94 is a female voice, while the following viola line is male, saying, ‘Don’t worry’. The last quaver of the viola part at bar 103 shouldn’t be too short – we have to sing it out. It doesn’t work if the violist makes a crescendo into bar 105 because there must be a contrast with the forte orchestral tutti in bar 105 (example 6). The crotchet in bar 105 should last exactly the right length – it must not be as short as if it had a dot – and in bar 106 the quavers must not be too short or spiky. The oboe and orchestral violin lines that accompany the violin solo from 107 are hopeless and full of pain, so the solo violin should not be jolly.

The oboe parts are more important than the solo here, so the violin has to be in the shade. Make these connections with the orchestra and create the illusion that one instrument is playing. This is not a concerto in which there is a battle between the soloists and the orchestra and the soloists tame the orchestra – it is a symphony. The solo violin must pick up the colour of the oboist, and then listen to the orchestral violins and adapt to their colour.

The viola solo from bar 115 leads all the way to bar 125 and finally at bar 126 we have arrived at where the concerto really starts for the soloists (example 7). But we have to think about this point from the very beginning and make it one long stretch. This is the architecture, a gigantic structure for Mozart’s time.

This section has a lot of humour. It’s as if both violin and viola are saying, ‘Life is great.’ I start more quietly, and try not to make each of the jumps the same. I wouldn’t use too much glissando at this point, or anywhere in Mozart. His music is a pure expression of Classicism: the aim for the sound is very clean –intonation has to be perfect. Not only do you have to be perfect when you are playing alone, but when you play with the orchestra you also have to match each other’s vibratos. If the orchestra does a huge vibrato and you don’t, it doesn’t work, and vice versa. And like a singer’s vibrato it has to be very controlled– it cannot be too wide.

Bar 143 is an aria for the soloists and you can both take time – it should sound like two human voices. In the solo runs from bar 149, the imitation has to be fantastic (example 8). The challenge is for the two instruments to blend – the colours must be the same. It should be like the work of a fantastic tailor – you don’t see the seams. Create the illusion of ‘who is playing where?’ Use as much vibrato as the horns, which are also playing; they’re not just accompanying but are creating the atmosphere. Each entry should contribute to the overall phrase, without accent. Bars 174 and 187 are like operatic recitatives, so the soloists can take lots of time and are not obliged to be exactly rhythmic, because of the flexibility of the accompaniment.

From bar 194 the four-note motif that passes round the orchestra is much more important than the soloists’ semiquavers, so the soloists have to fit (example 9). The solo violin has to be a bit darker because it is playing with the violas, while the solo viola has to be a bit lighter because it plays with the upper strings. This section often has the feeling of a party, with the soloists playing very loudly, but they should go into the shade, only developing in bar 202. From here the instruments imitate each other. This is a long line, in which the first violins have a theme that goes right through to bar 210 (example 10). This heralds my favourite section – the greatest master proves his genius in this development. It is in B flat major, so it feels like a celebration.

Harmonic interpretation – how you highlight the harmonies and their colours – is very important. If I were playing the violin solo at bar 288 alone, I would probably play the same way as in the exposition but I can’t in this case because in the recapitulation the horns are playing. Again, I have to adapt my vibrato, otherwise I will not fit into their line. The first time this theme occurs, in bar 125 (see example 7), it is without the horn part so it’s completely free. But this time it has to be different: Mozart never repeats the same thing – this is his genius. These are the little details that alter my performance and the impression the audience gets. This is how difficult and how easy it is: there are lots of things to investigate but once you understand it you are freed from decisions. Mozart has decided for you, if you only see these details and interpret them correctly. For example, the harmony here is different: this time it’s in E flat major – in the exposition it’s in B flat major. So the interpretation must be different. It’s important to be consciously reactive to these factors. For me E flat major represents enlightenment, B flat major has a more festive, playful feeling, G minor is dramatic and C minor is tragic. These modulations dictate how we put the colours on the table – it’s like painting.

In bar 325 it’s very tempting to be loud, to say, ‘Look how good my violin sounds.’ But the second horn part has to be heard too. Only in the crescendo of bar 327 can we play louder, making a crescendo into the tutti.

Throughout the piece, the violin and viola have to blend. When playing together in octaves, the lower one must be stronger, and then the two will sound like one instrument. If the upper octave is too independent, it’s like the separation between the first and tenth floors of a building. The viola can vibrate a little more and the violin a little less, because it’s on top – this is a general rule of acoustics. Crudely speaking, the viola has a dark sound and the violin is much lighter, so the violin has to try to play more darkly and the viola has to adapt to the violin, in order to create an illusion. People should wonder, ‘Who is playing now? Is it the viola or the violin?’ When you play together, get in touch with each other – try to speak the same language. When you share a phrase, you should be together and move simultaneously, to be one.

But everyone in this piece is a soloist – there is no accompanying. There should always be a definition of the priorities of the different roles and you have to know what these priorities are. So don’t play too much like a soloist – this is not just your piece. If you want to play solo, play a Mozart concerto.

INTERVIEW BY ARIANE TODES

Read: Masterclass: Nikolaj Szeps-Znaider on Mozart Violin Concerto no.5

Read: Masterclass: Mozart Violin Concerto no.4 in D major K218

1 Readers' comment