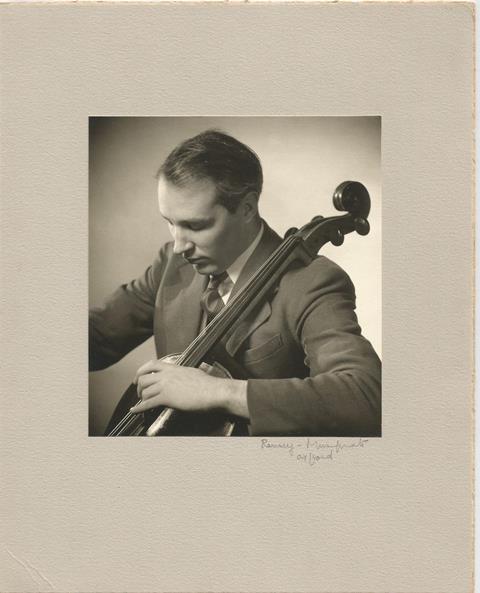

The distinguished cellist died last month aged 91. Dawn Gwilt shares the life story of her late husband, former co-director of the International Cello Centre with Jane Cowan and teacher of Steven Isserlis

John Gwilt (15 March 1930 – 26 September 2021)

A tribute by Dawn Gwilt.

John Gwilt was born in Edinburgh in 1930 into a family of distinguished mathematicians and economists. His father was an actuary and general manager of Scottish Widows; John’s elder brother George followed in those footsteps, becoming general manager of Standard Life, as well as being an excellent amateur flautist. The other three siblings, John, David and Lucy (Morris) all pursued professional careers in music – John as a cellist, David as pianist, composer and professor of music in Hong Kong, and Lucy as a violinist.

It was at Sedbergh School in 1943 that John first started learning the cello, and began what was to become a long-term association with the inspired cello pedagogue Jane Cowan, and her husband Christopher who was director of music at the school. With hindsight John realised how exceptional Jane’s training was, extending far beyond a weekly lesson; for example, she once invited John and David to stay on for a few days after the end of term in order to learn Schubert’s string quintet with herself, her half-sister Margaret Lockhart-Smith, and another student.

The Gwilt siblings played chamber music whenever possible. Back in the early days of the Edinburgh festival, artists were put up in local residents’ houses. On one occasion the second violin and viola of a famous Viennese String Quartet were staying with the Gwilt family, and John, Lucy, and David, playing cello, violin and viola respectively, persuaded the visiting professionals to join them in playing a Mozart string quintet. Of course, the quartet members were reluctant, but felt that they had to be polite to their hosts. During a playthrough of one quintet the guests became more and more enthusiastic, and after that began to decide which one to tackle next. It was huge fun, John and David remembered, as well as being quite a learning experience for the youngsters as well.

From 1948-1950, John did two years of compulsory national service. As an officer in the Royal Artillery, he was responsible for training signalmen to shoot using map references, known co-ordinates, distance, topography, wind speed, etc. One day on the firing range he was a bit exasperated with the men, so he grabbed the gun saying, ’Look, this is how you do it!’ Immediately after shooting, a massive display of flags came up. John assumed they were taking the mick, so he turned to his sergeant and asked what was going on. ’Perfect score, sir.’ John’s precise, orderly, and mathematical mind were evident, as well as his innate modesty.

During his national service, John decided to turn down a mathematics scholarship to Cambridge in order to study music professionally. He studied for two years at the Royal College of Music with Ivor James; but he was missing Jane Cowan’s inspirational teaching, so returned to study with her, first at Uppingham school, where Christopher was by now director of music, and then moving with the Cowan family when Christopher became director of music at Winchester, where John taught the cello, studied with Jane, and continued to build his performing career. During this time John took part in master classes with the great Pablo Casals and Casals’ student Maurice Eisenberg, as well as having lessons in Paris with Bernard Michelin.

In their early 20s, John and his brother David formed a successful duo partnership, giving their Wigmore Hall debut in 1956, recording regularly for the BBC and playing concerts in London and throughout the UK. The brothers were also taken under the wing of Adila Fachiri (great-niece and student of Brahms’ friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim) and played with her as members of the Fachiri Trio for ten years. John often recalled the long rehearsals of slow intonation practice for strings only, and wondered how many young musicians would have the patience for that today. It was a busy period in John’s life, divided between teaching at Winchester, touring with David, giving recitals with the Fachiri Trio, and playing concertos (including the Brahms Double Concerto with Olive Zorian) as well as chamber music with Henry Holst, Orrea Pernel and others.

John played on his beloved Gofriller cello for his whole career. He always loved its deep, dark sonorities and rugged honesty, qualities which he captured in his own playing. Sadly, there are no known recordings of the Fachiri trio, and I only know of a few BBC recordings of John and David, where the sound of John’s uncovered gut A string gives a rough-hewn honesty that is reminiscent of Casals.

John was gaining a reputation as a performer and teacher, and in the late 1960s Maurice Eisenberg and his assistant Millie Stanfield, who ran the International Cello Centre in London, asked him to take on the running of this school, as both were retiring. By this time, John and Jane’s relationship had transitioned to that of colleagues, and he knew that with her vision and his practicality, together they could make something special of this enterprise. In 1967 they joined forces and took on the running of the International Cello Centre in London. They started a weekly cello club, with cellists of all standards combining to play music for cello, much of it in arrangements by the Cowans or the Gwilts (John or David). They also started Saturday morning chamber music for both young students and older players, and Saturday afternoon playing classes. To these latter were brought, around 1969, the Isserlis family; they soon became regular attendees at all Cello Centre events.

Annette Isserlis recalls: ’One of my strongest memories of John is of a Saturday morning coaching session at ICC in Ladbroke Grove, where we were struggling with Dvořák’s ‘American’ Quartet. I should add that, although I was 17, I had only been learning the viola (from scratch) for a year or less. John listened impassively for a few moments and then stopped us. He described the scene we should be picturing as we played the opening: rustling leaves; the sun glinting in the brook; birdsong…and then, looking meaningfully at me, a wild boar comes crashing out of the undergrowth!’

The ICC expanded and rapidly became a thriving musical hub. When in 1970 David Gwilt moved to Hong Kong to take up the post of professor of music, John decided to devote his time and energy to teaching and running the ICC with Jane; though still performing, including giving outings to musical rarities such as works by Casals’ friends Donald Tovey and Emmanuel Moor. During the early 70s John took a prominent role in co-organising with Jane memorable annual ICC courses held in Schloss Breiteneich in Austria, and the nearby Benedictine monastery in Altenberg; where orchestral concerts took place in the magnificent monastery library or crypt, including concerto performances, such as the Brahms Double which John performed with Lucy Cowan.

When Christopher Cowan inherited a grand property in the Scottish borders, Edrom House, the ICC first began running residential Easter courses there for children; then in 1974 John and Jane took the decision to move the ICC up to Scotland in order to run a full-time residential music course. Students came from far and wide to study, including some from the US. John and Jane, along with Jane’s musical family, Francis Cowan, his wife Christina, and Lucy Cowan, created an exceptional learning environment, where Jane’s charismatic and sometimes mercurial style could flourish alongside John’s steady, calm, stabilising influence. During this time John also taught one day a week at the Royal Scottish Academy in Glasgow.

Steven Isserlis remembers: ’Those of us studying with Jane Cowan at the Cello Centre in London and Scotland were lucky enough also to have lessons with her co-director John Gwilt. He was Jane’s rock, a quietly humorous man who provided much-needed stability at the Centre; where Jane was an inspired visionary, John was practical, wise and thoughtfully helpful, with his own brand of unshowy charisma. Unlike Jane, John still gave concerts - both public and private - to which we all looked forward. At the romantic setting in Scotland (Edrom House) to which the Centre migrated in 1974, John would sometimes play the Bach suites for us students in the evenings, sitting in front of the log fire; it was a wonderful way to be introduced to these masterpieces. We all looked up to him, respecting his profound musicianship and enjoying his company and wit. He was a deeply loveable man.’

Read: Steven Isserlis shares his memories of cellist Marius May

I first met John in 1978 when I came to study at the ICC as a full-time student. Initially I felt somewhat intimidated by his intellect and what I perceived to be his aloof manner, but gradually I began to see beneath the exterior to a very wise, caring, and deeply sensitive man and musician. When I returned for my third year of study I was no longer just a student, but also a teaching assistant. Because of this John relaxed his strict boundaries, and a different relationship developed between us. In 1981 we got married, which was a delightful surprise for many, including John, who had assumed that he was destined to live life as a confirmed bachelor.

John had always believed that his future would involve continuing to run the ICC. Sadly this wasn’t the case, and it was a seismic transition for him to take on peripatetic cello teaching as a next step. He did so with good grace, and inspired many young cellists over the next 15 years, as well as being drafted in for the concerts of many local amateur orchestras and choral societies in Worcestershire. John believed that young children are innately open to music of any sort, and he refused to dumb-down for a primary school demonstration. He loved to play something unexpected, like a short movement from the Henze Serenade, performed with character and imagination, invariably invoking laughter and delight from the children.

After John retired, he and I played much chamber music locally. He loved a challenge, and took great pleasure in playing viola parts on his cello – anything from Mozart quintets through to late Beethoven quartets! This was fortunate for me, as the chamber music repertoire involving two cellos is limited. We spent many hours rehearsing the lower parts of Beethoven quartets, which was surprisingly satisfying, even without violins. He continued teaching local amateurs right up to his mid-70s, and he played a daily Bach Suite until his 86th year, when it became too difficult physically. He accepted this loss with equanimity, and though his energy and mobility declined, his mind was very sharp right to the end, reading his beloved P.G. Wodehouse and solving cryptic crossword puzzles.

With his understated manner and penetratingly sharp mind, John loved coming up with creative solutions to both technical and musical problems, based on ease and economy of movement, which he irreverently referred to as his ’philosophy of laziness’. I benefitted so much from his teaching over the decades, and this lasted right to the end of his life. Whenever I went to him with a technical or musical conundrum, he would invariably say in his modest way, ’I’m not sure if I’ll have anything to say…’ and then would proceed to find a unique solution or a suggestion that helped tremendously.

John had a steely self-belief, underneath which lived a very sensitive soul. I can’t think of him without picturing his hands – beautifully poised, still, and radiating serenity. He was extremely self-contained, but never cold, and in some ways the monastic life would have suited him. He was an excellent listener; unflappable, ready to offer calm, solid support, and his loyalty was absolute. He will be sorely missed.

Read: ‘It’s important to be emotionally authentic – you mustn’t give false messages’ – Steven Isserlis

Read: Long read: Remembering Jacqueline du Pré

Read: Kenneth Essex, violist for The Beatles, has died

No comments yet