- News

- For Subscribers

- Student Hub

- Playing Hub

- Directory

- Lutherie

- Magazine

- Magazine archive

- Whether you're a player, maker, teacher or enthusiast, you'll find ideas and inspiration from leading artists, teachers and luthiers in our archive which features every issue published since January 2010 - available exclusively to subscribers. View the archive.

- Jobs

- Shop

- Podcast

- Contact us

- Subscribe

- School Subscription

- Competitions

- Reviews

- Debate

- Artists

- Accessories

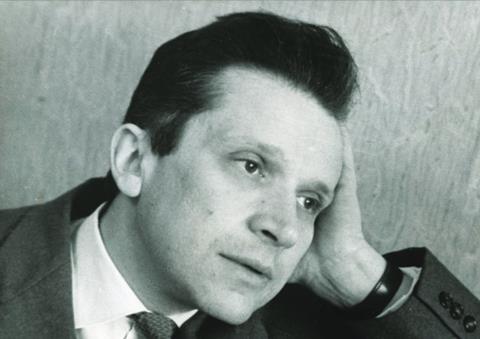

Gidon Kremer on Mieczysław Weinberg: Testament to turbulent times

2019 marked a century since the birth of Polish–Soviet composer Mieczysław Weinberg. Violinist Gidon Kremer tells Tom Stewart why he has become one of the composer’s greatest champions

In a 2015 interview for the International Mieczysław Weinberg Society, Shostakovich’s widow, Irina, recalled her surprise on hearing that ‘Gidon Kremer, who was so avant-garde, had fallen in love with Weinberg’s music!’ Kremer laughs when I put this to him. ‘When I was young I was more interested in people like Schnittke, Arvo Pärt and Sofia Gubaidulina. These exciting composers were still relatively unknown and their music needed support. I was always opposed to the totalitarianism of the Soviet Union and I didn’t think that spending too much time focusing on the “classic” Soviet artists, as Shostakovich became, was a good thing. Weinberg fell into that category, too.’

Since then, however, Kremer has become one of the composer’s greatest advocates. Last year he directed a weekend of celebrations at Birmingham’s Symphony Hall, with his eponymous Kremerata Baltica alongside the City of Birmingham Symphony Orchestra (CBSO) and its Lithuanian music director Mirga Gražinytė-Tyla; and this month sees a performance alongside the CBSO and Gražinytė-Tyla of Weinberg’s 1959 Violin Concerto. ‘In his centenary year,’ says Kremer, ‘I’m glad to have the opportunity to do as much as I can to correct the mistake I made when I was younger.’

Angular, focused and uncompromising, the music of Weinberg is often likened to that of Shostakovich, with Weinberg sometimes considered an informal student of his distinguished senior. Kremer disagrees: ‘They each had so much respect for each other as artists and friends that it isn’t always possible to tell who had the greater influence. Weinberg was such an individual voice and his music is perhaps even more personal. I’m not at all denying Shostakovich’s greatness, but I feel like Weinberg’s time has come.’

Born in Warsaw in 1919, Weinberg fled to Minsk in 1939 while his parents and sister remained in Poland. Like much of their family, they were killed in the Holocaust, whereas Mieczysław, along with many Soviet musicians who were not enlisted in the Red Army, was evacuated to Tashkent in modern-day Uzbekistan. It was there, in 1943, that he first met Shostakovich, who was visiting its displaced musical community from the besieged city of Leningrad. The two quickly became close, and although Shostakovich was sanctioned more severely in the post-war crackdown on artistic freedoms, he was nevertheless able to help save Weinberg’s life in 1953 after the latter was detained on anti-Semitic charges. Shostakovich adopted the younger composer’s daughter to ensure her safety before using his political connections to secure Weinberg’s release, which was made more likely in any case by the death of Stalin soon after.

Already subscribed? Please sign in

Subscribe to continue reading…

We’re delighted that you are enjoying our website. For a limited period, you can try an online subscription to The Strad completely free of charge.

* Issues and supplements are available as both print and digital editions. Online subscribers will only receive access to the digital versions.