Many, if not most, of the earliest bow makers working in America originally hailed from Germany. Raphael Gold discovers how they helped lay the foundations for the industry

Discover more lutherie articles here

Read more premium content for subscribers here

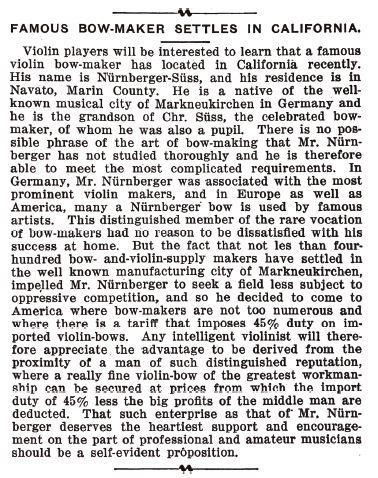

Tracing the arc of American bow making is a tricky business. There have been nearly as many influences in its history as bow makers, and their traditions range from the self-taught to the rich heritage of French master makers. The earliest wave of bow making in America was a group of unaffiliated German immigrants, beginning in the mid-1870s. What drew these makers to the New World? Influential violin shops run by German master craftsmen took root across America as German immigration swelled, reaching nearly three million German-born immigrants by 1890. In the late 19th century, American government raised its funds mainly from tariffs on all manner of imports, including musical instruments. A central political issue of the day, tariffs averaged a whopping 45 per cent by 1911. Some makers saw the potential in moving to America and establishing a local foothold protected by the tariffs. Dealers in America sought ways to avoid tariffs by importing the actual German bow makers themselves; while others were already in the US when they saw an opportunity to dabble in, if not focus on, bow making. Each of these makers has a unique story to tell, highlighting the complex business relationship between the musical worlds of America and Germany before World War I.

The first German bow maker in America was Carl Heinrich Ludwig Bausch, known as Ludwig Bausch Jr. He visited New York City in the autumn of 1859 to set up an agency, intending to sell violins and bows – importantly, bows of his own making. His arrival excited wide interest, allowing him to sell his wares in other cities as well, including Baltimore. At this time tariffs were relatively low in America, and his motives were likely an attempt to expand business beyond Europe. Despite his fame, he only remained in America for about a year. Although his attempt at establishing a foothold was ultimately unsuccessful, he may well have been the first professional bow maker ever to work in America.

Anton Siebenhüner was another early bow maker in the States. Although he stayed for a very short period of time (1874–78), those years catapulted his career. Born in 1851 in Schönbach (then a part of the Austro-Hungarian Empire) he studied with Gabriel Lemböck in Vienna, then for two years with Alois Engleder in Budapest, then Andreas Engleder in Munich and Thomas Zach in Vienna. Following brief stints with Ludwig Bausch Sr in Leipzig and Karl Grimm in Berlin, he moved to New York City in 1872 to work as a master maker in the workshop of George Gemunder – as his first employee. In 1874 the young and surprisingly experienced Siebenhüner set up his own shop at 315 Sixth Street. Two years later he won first prize at the Centennial Exhibition of Philadelphia in 1876 (the first of its kind in America), probably for both bows and instruments. Though Siebenhüner is most known as a violin maker today, Henri Poidras, in his 1928 Dictionary of Violin Makers Old and Modern, calls him a ‘good class bow maker’. He moved to Zurich, Switzerland, in 1878, establishing a thriving shop. He died in 1922.

Henry Richard Knopf was arguably America’s first prolific bow maker. Born in Markneukirchen in 1860, he studied bow making with his father, famed bow maker Heinrich Knopf, and his uncle, Wilhem Knopf. He studied violin making with Bausch in Dresden and Christian Adam in Berlin. In 1879 he immigrated to America, to work for John Albert in Philadelphia. He first appears in the 1880 Philadelphia census, living with a couple of Russian citizens in the home of a saloon keeper. Understanding his potential, he opened his own business in New York City in the latter part of 1880, thus etching his name in posterity.

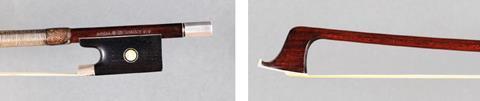

Early in his career, he worked to establish himself as a maker of bows and instruments, clearly taking advantage of the protectionist high tariffs. Several encyclopaedias estimate he made around a thousand bows. Poidras understates that H.R. Knopf was ‘a talented violin and bow maker’.

Knopf was the only maker to have exhibited his bows at the first convention of the American Guild of Violinists, on 6 and 7 October 1911. The Guild was formed specifically to support and promote making in America, an early example of its kind. He exhibited a cello bow and violin bow again the following year, receiving high praise for his work. He continued to be a central element of American violin and bow making by supporting the first meeting of the American Violin Makers Association in 1924.

At the same time, he had ambitions to exploit his contacts in Europe. He was naturalised in New York City on 13 May 1887, and applied for his first passport five days later. And as long as he was in business, he kept his passport up to date, regularly making publicised trips to and from Europe where he sourced old instruments and bows. During these business trips he would have also met with contemporary makers, including Eugène Sartory, importing their work.

He was active in all aspects of the business throughout his career. Apart from making and repairs, he was an expert witness in several court cases, including one against Victor Flechter in 1890 (see page 58); he was elected one of the vice presidents of the thriving American Academy of Violin Makers in 1914.

The business had grown so much that in 1921 he was obliged to relocate to larger premises, from 127 West 42nd to 145 West 45th. That same year his two sons, Eugene and Richard, formally joined the business, forming H.R. Knopf and Sons. Eugene had shown ‘great aptitude for violin making’ assisting his father in the shop; Richard, who had a degree in business, was announced as taking care of the advertising and sales management side of the business. They advertised heavily that year. By 1922 they had agents selling H.R. Knopf violins and bows in several states, including Vermont, Michigan, Ohio, and beyond. The great cellist and composer Victor Herbert owned and used a Henry Knopf cello; renowned violinist Maud Powell was also a regular customer of his. His bows and instruments were celebrated throughout America.

Keil’s bows, branded with Flechter’s name, were given to such luminaries as Joseph Hollman, Maud Powell and Pablo de Sarasate

According to his obituary, the business was dissolved in 1931 when he retired. In December 1939 an advertisement from Wurlitzer’s stated the company had ‘made a timely purchase of the entire stock’ of H.R. Knopf and Sons and were selling it off.

Of the plethora of respected shops in NYC, it can be argued that John Friedrich and Brother was the best. John apprenticed with Joseph Schonger, violin maker in Cassel. He also worked with Möckel in Berlin, Hammig of Leipzig, and shops in several other German cities including Stuttgart before immigrating to America in 1883. That same year he opened a shop with his brother William, who was already living in America. At the 1893 World’s Columbian Exposition in Chicago, John won a gold medal for ‘a handsome exhibition… of a number of his violins, violas, violoncellos, and several bows’. By the time America entered World War I he was employing a large repair staff, was importing large quantities of bows, instruments and accessories, and was the appraiser for the United States Government. No doubt the large quantity of imported bows bearing the firm’s name has overshadowed the fact that he made bows in the early years. It is probable the bows he made himself were branded with his name, rather than the shop name.

Perhaps the most mysterious German bow maker working in America only stamped his bows with the name of his employer: Victor Flechter. This mysterious bogenmacher was Anton Keil, mentioned erroneously in Wenberg and Jalovec as ‘Kiel’. In Harvey Whistler’s unpublished notes, compiled for his unfinished book Bow Makers of the World, some details emerge of this most enigmatic bow maker, but even then his full name was previously unknown. Genealogical research brings him a little more into focus.

Anton Keil was born in September 1865 in Schöneck, Saxony. It is still unknown where he learnt bow making but he likely started in Markneukirchen. He departed for New York on 17 October 1889, listing himself as ‘instrumentenmacher’. In census records he is listed as a violin maker living in Manhattan. It also appears he made a trip back to Germany before returning to NYC in 1894. He started working for Flechter on arrival in 1889, although he never received recognition by his boss for his work. His name did not appear in any advertisement and, unlike most of his peers in New York, he was apparently never mentioned in a newspaper article.

The timing of Keil’s trip to America right after his 25th birthday is significant. Victor Flechter, born in 1849, was a native of Cincinnati where he was a respected musician and teacher. A well-connected man of ‘pleasing appearance and suave manner’ who spoke English, German and French, Flechter made his big move to NYC in 1888, where he encountered a saturated market of well-established violin houses. He publicised the success of his first business trip to Europe in 1889, returning with large quantities of instruments and bows for sale. It was on this business trip that he likely found Keil and hired him.

According to Whistler, Keil’s bows, branded with Flechter’s name, were given to such luminaries as Joseph Hollman, Maud Powell and Pablo de Sarasate. The Strad (October 1900) states that Flechter counted among his close friends the likes of Joachim, Wilhelmj, Marteau, Reményi and Ole Bull. Many of them surely owned a Victor Flechter bow made by Anton Keil. The Violin Times said Flechter presented one of his bows to Eugène Ysaÿe in 1895. A bow was presented at the 1904 Louisiana Purchase Exhibition. During most of the year Keil repaired bows and instruments for Flechter, but worked ‘prolifically during the slack summer months’. Keil was an unheralded artist, seemingly content to work for no glory.

It is interesting that Keil was able to make bows at all, as Flechter’s time in the business was plagued by scandals. In 1890 the young violinist Maud Powell accused him of selling her a fake Duiffopruggar for $500, which was apparently purchased from Henry Knopf for $40! He was also sued by an important violinist, Max Bendix, under similar circumstances. Of the multitude of shady dealings publicised in the press, one nearly landed him in Sing Sing prison in 1895. Following a multi-year legal battle where he was accused of stealing a Stradivari violin, causing the death of its owner, Flechter was finally exonerated, leaving a tarnished legacy. With such a boss, Keil kept his head down and worked silently; perhaps he was content making a living and not being publicly affiliated with such infamy.

Keil appears to have worked in NYC at least until 1910 – a rather long 21-year temporary stay, never marrying or seeking US citizenship. He reappears in Schöneck, Saxony, in 1929, as a geigenbogenmacher living on 18 Oelsnitzer Str, though he likely left before the outbreak of WWI, leaving behind a number of interesting, if obscure bows and many more questions.

Hiring a German maker to live and work in America was a popular business model at this time

Franz Winkler worked in America for only two years but developed a lasting reputation as a maker of good bows and close business relationships. Born on 20 October 1878, he studied bow making with his father Franz Heinrich Winkler in his native Markneukirchen. He worked for Karel van der Meer in Holland as a bow maker before possibly returning to Markneukirchen to set up on his own.

It was in August 1903, aged 24, that he set sail for Philadelphia to work for the dealer Julius Gütter (who trained the young William Moennig Sr). It seems that Winkler was important enough a maker that Gütter personally escorted him from Germany, along with 24-year-old Conrad Heberlein, Gütter’s cousin and violin maker. According to Wenberg, Winkler made bows that were branded with Julius Gütter’s name (it would likely have been spelled ‘Guetter’), similar to the relationship between Victor Flechter and Anton Keil. Hiring a German maker to live and work in America was a popular business model at this time, allowing the dealer to circumvent the high rates of the 1897 Dingley Tariff Act. The idea was to manufacture good German bows in America.

Winkler stayed for a very short time before moving to Chicago to work for Robert Pelz, where his bows became quite popular with members of the Chicago Symphony. Most likely American city life was not for him, and he returned to Europe in 1905. After a brief stint in Paris, he returned to his roots in the German countryside where he later owned a restaurant and small farm. By 1928 Carl Fischer of New York was the ‘sole American agent’ of his bows.

Taken as a group, these German makers qualify as the first bow making wave in America. They all acted under the same historical pressures, with tariffs in America’s growing economy creating an opening for the intrepid bow maker and businessman. Several of these German-born makers saw themselves in a historical role, joining upstart American ‘guilds’ and promoting American bow making with exhibits in various World’s Fairs. Today it is easy to forget that, apart from the Englishman Edward Tubbs, the first attempts at bow making in America were done by German immigrants, who together formed a seminal role in American musical culture.

The Schuberts

The history of San Francisco’s very own bow making family

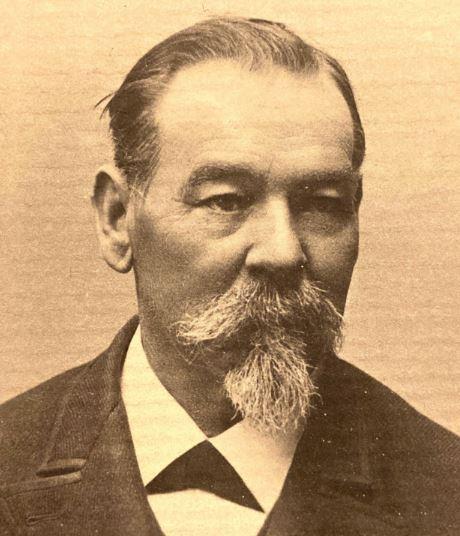

The Schubert family had an outsized, if unrecognised, impact on musical life in the San Francisco Bay Area. Richard Schubert, the first in the family to resettle, worked there for nearly 60 years with a stellar reputation, making and repairing. He brought over his brother Christian Wilhelm Schubert to help him in his shop; Richard was likely the exclusive agent of his more famous brother, Paul Schubert, importing his bows in large numbers; his sister, Anna, moved to California’s Bay Area with her famous bow making husband, August Albin Nürnberger, known as Nürnberger-Suess. It is also possible Anna helped make frogs for some of her husband’s bows.

August Richard Schubert was born into a violin and bow making family on 22 December 1872. After an apprenticeship in his native Markneukirchen, he worked for Carl Zach in Vienna and later Otto Miggs in Koblenz. When Miggs moved to London, Schubert followed; Hill & Sons found his repair work excellent, and apparently made use of his talents. He moved back to Markneukirchen around 1898 before immigrating to America in 1900 to head the newly expanded violin department of Sherman, Clay & Co. While there, he primarily did high-end repairs, but also made several violins. In 1910 he set up his own shop at 101 Post St and remained there until 1959.

Needing an extra hand with his new shop, he brought his 35-year-old brother Christian Wilhelm to San Francisco from Markneukirchen, Germany. Born in 1875, Christian probably had similar training as his older brother, though did not enjoy as wide a reputation. William, as he was known, stayed with his brother from 1910 to 1930 before retiring. He died in 1936.

While Richard advertised as a violin and bow maker, receiving accolades from the likes of Yehudi Menuhin, Fritz Kreisler, Eugène Ysaÿe and Jan Kubelík, it is clear that Willi made and repaired the bows, stamping at least one which was presented to Ysaÿe on a well-publicised concert tour to the Bay Area in 1913.

While local oral tradition has it that Paul Schubert lived in San Francisco (it is also printed in Wenberg), the historical record does not support this claim. We know Paul worked with Nürnberger-Suess in Germany until the latter moved to America in 1912; he also appears in the directories and World Book in 1925, 1929, and 1937 on, in Adorf, near Markneukirchen. I have never seen his name as violin or bow maker in any directory in San Francisco, he is not in any immigration record or census, there is no mention of his name in any newspaper article, and he had no advertisement in any contemporary Bay Area periodical. If Paul, whose bows were sold in large quantities in the Bay Area, were in San Francisco working with his brother, he would have made his presence known, and there is simply no trace of him in the historical record.

Nürnberger-Suess, on the other hand, arrived in San Francisco with fanfare (see ‘Bows on the Bay’, November 2021). The economy in San Francisco was healthy and growing at a fast pace, and had a thriving music scene, with theatre orchestras and vaudeville orchestras of all kinds, including the newly formed San Francisco Symphony. Musicians were thirsty for a professional bow maker. Obviously an adventurous spirit, Nürnberger-Suess was willing to try a life in what was then a far-flung part of the world. The family moved an hour north to rural Novato shortly after arriving, Richard Schubert loaning the money for the property. Apart from his bow making, Nürnberger-Suess was also a farmer, having a contract with the Almond Board of California. He not only sold his bows locally but he also advertised nationally in The Violinist during the 1920s, and even tried teaching the next generation of California bow makers in Alfred Lanini.

Read: Bay Area bow makers: Bows on the bay

Read: ‘The great artistry of history’s most important bow maker’ - François Xavier Tourte

Discover more lutherie articles here

Read more premium content for subscribers here

An exclusive range of instrument making posters, books, calendars and information products published by and directly for sale from The Strad.

The Strad’s exclusive instrument posters, most with actual-size photos depicting every nuance of the instrument. Our posters are used by luthiers across the world as models for their own instruments, thanks to the detailed outlines and measurements on the back.

The number one source for a range of books covering making and stinged instruments with commentaries from today’s top instrument experts.

American collector David L. Fulton amassed one of the 20th century’s finest collections of stringed instruments. This year’s calendar pays tribute to some of these priceless treasures, including Yehudi Menuhin’s celebrated ‘Lord Wilton’ Guarneri, the Carlo Bergonzi once played by Fritz Kreisler, and four instruments by Antonio Stradivari.

No comments yet