Charlotte Gardner reports from a newly reinvigorated and audience-friendly Vibre! Bordeaux festival and International String Quartet Competition

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

The 2022 edition of the revitalised triennial Bordeaux International String Quartet Competition soon proved that it had become that rarest of competition breeds: an event that at least as many people would want to attend as would want to win.

Founded in 1999 by cellist Alain Meunier and Bernard Lummeaux, Bordeaux has long been worth paying attention to. The 1999 edition was won by the Belcea Quartet and in 2003 the Ébène Quartet took first prize. Recent winners are the Schumann (2013), Akilone (2016) and Marmen (2019) quartets. Adding to the interest, it’s also been a competition ready to experiment, with the 2019 edition dispensing with standard semi-final and final rounds, the six quartets competing instead across three concerts. Yet, like many big string quartet competitions, the Bordeaux has also always appeared strangely hidden away, with barely an online presence, and still less significant international PR or remote viewing options.

But in 2020, Meunier and Lummeaux handed the artistic direction to the Modigliani Quartet, and general direction to impresario Julien Kieffer, also brother of the Modigliani’s cellist, François Kieffer. The competition was renamed Vibre! and reimagined to incorporate a festival – running alongside the competition during competition years, and as a stand-alone the rest of the time.

For the 2022 competition, the Opéra National de Bordeaux, under its new general director, Emmanuel Hondré, not only hosted but acted as co-producer and co-financier. For the first time, all rounds took place in the Opéra’s city centre auditorium with its chamber-friendly acoustic. The competition was streamed internationally, incorporating concerts by the Modigliani, jury members and others, and featured a collective of luthiers in the auditorium’s foyer, making a Guadagnini-copy viola from scratch. There were also further free public concerts and conferences in the city. The prizes included cash, concerts, the opportunity to record an album with label Mirare, and a set of bows by sought-after Paris bow maker Edwin Clément. The jury was made up of active performers, dominated by representatives from the world’s leading quartets, including Veronika Hagen (Hagen), Ori Kam (Jerusalem), Antoine Lederlin (Belcea), Gabriel Le Magadure (Ébène), plus pianist Momo Kodama and composer Kaija Saariaho.

Read: Brodsky Quartet at 50: Life is an adventure

Read: Masterclass: Beethoven String Quartet op.132

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

When I arrived, midway through the semi-finals, I could already feel the magic. By this point, there had been the usual Covid-related last-minute absences: Martin Beaver of the Tokyo Quartet was replaced as president by Lederlin, his own jury shoes subsequently filled by Modigliani first violinist Amaury Coeytaux, and Saariaho was remote-judging the readings of her Terra Memoria from home. Yet the music that Friday afternoon from the Adelphi, Barbican and Chaos quartets felt more like a concert than a competition, performed to a packed audience that gave back tumultuous, extended applause.

This impression only deepened during the first interval, as I watched intrigued audience members crowding around the hard-at-work luthiers in the foyer. And when I went backstage to speak to the Barbican Quartet, they were all smiles. Eventually taking third prize, the Barbican had applied after participating in 2021’s inaugural Vibre! Festival, and the musicians were especially looking forward to feedback from the all-player jury. ‘With teachers, you play for them in a lesson but they don’t always hear you in the concert,’ pointed out first violinist Amarins Wierdsma. ‘Here, we’re giving everything, our nerves and emotions at their highest, and they can help us – perhaps with nerves, or projection – with their own experience.’

The good vibes continued with the announcement of the finalists. There were fears that favourites the Leonkoro Quartet – fresh from winning the Wigmore Hall International String Quartet Competition the previous month – wouldn’t make the cut on account of a weaker Mozart Clarinet Quintet (with guest clarinettist Nicolas Baldeyrou). But they progressed nevertheless, signalling that this was a jury with a big-picture attitude.

A collective of luthiers were in the foyer, making a Guadagnini-copy viola from scratch

‘You can say this or that piece was perhaps not a quartet’s best, but there’s so many things that add up,’ Coeytaux said afterwards. ‘The panel too is a dream for us. It’s all the quartets one really admires, and we have complete confidence in them all, because we know them both artistically and as humans. We also barely ever have the chance to be in the same place or play together. So this week is very special.’

Pointing out further benefits of jury members performing themselves, the Modigliani’s second violin, Loïc Rio, continued: ‘We may all be performers, but it’s always possible that during the week one might slightly forget what it’s like. So to be on stage and feeling the pressure yourselves is a reminder. It also demonstrates that we are all a family in the quartet world. Fighting over who will have a career and who won’t is not how it works. There’s space for everyone. Which is why the competing quartets are invited for the whole competition, and if they don’t progress, they have a concert in the city for which they receive a regular fee – because they are already a quartet; and we’re happy, because almost all of them are attending most of the competition.’ So most competitors would also have heard Modigliani viola player Laurent Marfaing step on stage on finals night to play solo Bach on the newly finished (but as yet unvarnished) Guadagnini copy, filling the hall with excitingly big, crisp-edged and wild-sounding tones.

A few performance moments deserve special mention, beginning with the exhilaratingly multi-coloured and flowing Ligeti String Quartet no.1 from the Chaos Quartet, who won the second and contemporary prize. Also, the Barbican Quartet cast a spell over the hall in the Adagio molto of Beethoven’s String Quartet op.59 no.2. Then there was the Leonkoro’s gripping opening to Beethoven op.59 no.3, each of its introductory chords an entirely new sound world of style, texture and timbre, and an Allegro molto finale of electrifying, feather-light, Mendelssohn-like vim.

The Leonkoro Quartet was the eventual winner of the first, audience and young audience awards, and unsurprisingly, the musicians enjoyed their Bordeaux experience. ‘The great thing was that it was inside a festival,’ mused cellist Lukas Schwarz. ‘Of course the atmosphere is tense in a competition, but you were able to go to concerts, see your judges play, the Modiglianis were always around, and you felt they really understood and knew how to lead you through the week, because they had relatively recently done what you were doing.’ Plus, the Leonkoro’s concert diary is now fuller than ever. ‘It sounds a bit unromantic,’ apologised Schwarz, ‘but what winning the Bordeaux means for us, and after the Wigmore too, is that we can make a living out of this thing. No more competitions. Which is crazy, because we couldn’t have imagined this one year ago!’

Hondré was also thrilled. ‘The biggest difficulty for a competition is to make it feel as though you’re in a concert,’ he stated. ‘What I love from both Alain Meunier and the Modiglianis is the idea that a competition isn’t something with a fixed form. That we must give ourselves the freedom to allow the music to breathe and exist. So I have found this year’s formula very beautiful. Truly, they’ve made a perfect balance between competition and festival.’

Read: ’The good news keeps coming’: Leonkoro Quartet scoops victory at Bordeaux, signs management deal

Read: Contending for the crown: Postcard from the 2022 Queen Elisabeth Competition

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

-

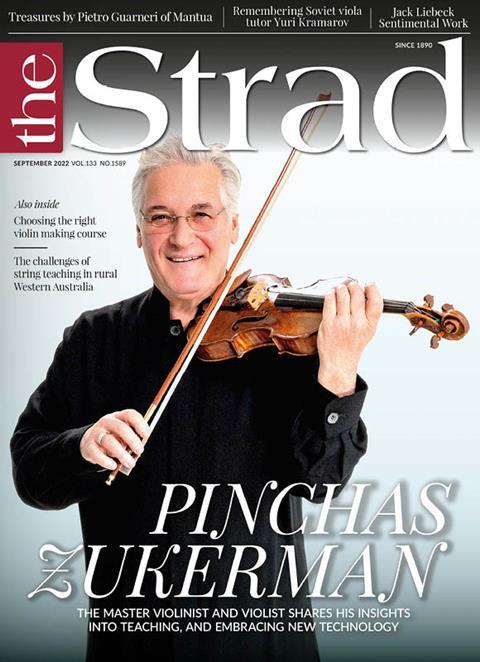

This article was published in the September 2022 Pinchas Zukerman issue.

The veteran violinist and violist tells Pauline Harding his views on everything from his new masterclass series to the role of technology in string teaching . Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- Pinchas Zukerman

- International Lutherie Schools

- Newark School of Violin Making

- Strings in regional Western Australia

- Villiers Quartet Session Report

- Pietro Guarneri of Mantua

Read more playing content here

-

![[1st prize] Poiesis Quartet in round 3 (2)](https://dnan0fzjxntrj.cloudfront.net/Pictures/100x67/1/9/5/41195_1stprizepoiesisquartetinround32_547631.jpg)

No comments yet