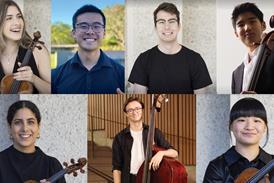

The term ‘folk music’ can encapsulate a multitude of genres, so what does it mean to Nancy Zhou? The violinist outlines numerous folk music influences that provide a cross-fertilisation of music, culture, and social justice

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

On the way to school during elementary and middle school years, my mother would regularly play the same album of ballads by the Taiwanese singer Teresa Teng. The signature tender croon of the 1900s ’eternal queen of Mandopop’ enveloped these quotidian trips in melodic warmth and more - velvet articulation, a soothing, variegated vibrato, and glissandi so sorrowfully sweet that it made me think of the erhu, a traditional Chinese bowed instrument which my uncle played professionally for decades.

Young me didn’t think much about the backstory of either these songs or Teresa herself. At that point, she was simply an idol who happened to convene all of my memories and thoughts related to folk music - my mother is a former professional folk minority dancer, and my father, who was my violin teacher throughout my youth, hails from a family of traditional Chinese musicians.

It was only some years later that I learnt that Teresa Teng was as much a cultural icon as she was a musical one - a peacemaker and superstar by any estimation. Her music allowed individuals to be seen during turbulent times, subverting the collectivist and censorship mould prescribed by the Cultural Revolution and symbolising unity, compassion, and ideals of the romantic spirit.

She had the gift of capturing that plaintive longing permeating the hearts of the estranged people of Taiwan and China, to whom I felt so distant yet so close. So close because throughout my childhood as an American-born Chinese, I experienced China firsthand during summer trips to my mother’s hometown village in Guizhou (a province located in southwestern China), as well as vicariously through the stories my parents would recount.

These vignettes were shadowed by not only the Cultural Revolution but also their own childhoods - sentimental in its delivery and evocative in its content. Some images and feelings are still tucked away in the deepest folds of my memory. My mother’s nostalgia for the verdant mountains and gorges where her home was ensconced, her lovable interpretation of the rhythms of glutinous rice pounding, my father’s sombre retelling of living by the bootstrap during his studies at the Shanghai Conservatory (at one point he subsisted on a loaf of bread over a week).

What a juxtaposition, one may think. Yes indeed, but it was precisely these disparate elements - a spiritual bond with nature and severely modest social circumstances - that defined the ’folk music’ experience for me.

Music treads on the delicate line between the communal and individual experience; the primal and artful ways of expression; and, the simplicity and complexity of human understanding. Trained as a classical musician, I’ve devoted countless hours to these latter elements of written Western art music and deconstructing the formal techniques creating the magic of this art form.

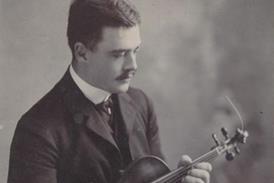

But I must say the single biggest breakthrough moment in my musical studies came when my ears landed upon the sound world of Hungarian composer Béla Bartók. Honest, angular, at times uncompromisingly violent in its expression, at other times utterly and beautifully haunting: these thoughts come to mind when I listen to Bartók’s music. His fifth string quartet, Concerto for Orchestra, and Sonata for Solo Violin (the latter two works written during the last three years of his life) formed my entryway into discovering the composer’s forensic studies of the musical language of Eastern Europe’s peasant folk.

For Bartók, ’folk music’ meant peasant music. It was a force created by a ’community which have had no schooling [and is] as much a natural product as are the various forms of animal and vegetable life.’ It was not only the artist and ethnomusicologist in Bartók that transfixed me, but also the social advocate whose writings were as uncompromising as his music. It offered a poetic parallel to his sentiments against urban frivolity and empathy for the backwardness of ethnic minorities.

Spurred on by my resonance with Bartók’s ethos, I visited the Bartók Archives in Budapest for the first time in September 2024, a month before my recording session featuring his solo violin sonata. If one wanted to get acquainted with the composer, pianist, and ethnomusicologist, the Archives was the place to be. It boasts a significant collection of primary sources such as compositional autographs and sketches, as well as documents belonging to Bartók’s personal library.

Needless to say, the sheer quantity of resources shedding light on the personality behind the legend made me feel like a kid in a candy store. When I opened that one notebook and set eyes on the preliminary sketches of the solo violin sonata, those childhood threads weaving the fabric of my subconscious experience with folk music resurfaced: the melancholic ballads from Teresa Teng, the summer excursions to my mother’s village, the struggling, hard-toil times of my father as a schoolboy… Now Bartók had taken over Teresa’s role as the gatherer of memories.

Inspired, I concluded this trip in Budapest with the boisterous pulse and rhythms inhabiting a local Hungarian tavern located in the city’s ‘Pest’ district. Here, locals extended themselves with abandon and cheered to music until dawn. A band of six musicians, a few clad in traditional Hungarian clothing and all accompanied by beers, graced spectator’s ears with music that profoundly stirred.

I remember being riveted by each musician, especially the crosslegged violinist whose fiddle was so casually propped that his posture would be easy target for some serious scrutiny among violin teachers. Then there was the female musician, whose voice melded singing with wailing and gleamed across strong inflections, reminiscent of the voices from my mother’s village.

It was a live folk music event that invited participation of all senses. The malted merriment, knock of pint glasses, invigorating embrace of human heat, romping stomps to the rhythms pulsating through the ground - these were participatory, not presentational, gestures. And it was utterly liberating.

From that point forward, on this continuum of music as a way of life, I placed my faith in a cross-fertilisation of music, culture, and social justice. And the agent for that cross-fertilisation? Folk music - the force that simultaneously withdraws into itself and invites participation from shared experience to find meaning.

Nancy Zhou’s upcoming album Stories (re)Traced is released on Orchid Classics on 6 June 2025 and will feature Bartók’s Solo Sonata. The Double of the Sarabande from Bach’s Partita no.1 is released as a single on 23 May 2025.

Read: Three bows are better than one: Nancy Zhou shows off the tools of her trade

Read: Apollo Chamber Players: when ‘diversity’ became dangerous

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet