Cellist George Neikrug, who died in 2019 at the age of 100, was a celebrated performer and orchestral principal. However, his skills as a pedagogue were second to none, writes University of Wisconsin-Whitewater professor Benjamin Whitcomb, who has gathered personal recollections

The following is an extract from an article in The Strad’s January 2021 issue remembering the cellist and pedagogue George Neikrug. To read in full, click here to subscribe and login. The January 2021 digital magazine and print edition are on sale now.

Alan M. Smith

Bowling Green State University professor emeritus of cello – Ohio, US

Mr Neikrug taught me so many invaluable techniques, philosophies and procedures from which I could basically teach myself. Before my first lesson I had developed a bit of tendonitis in my left wrist, which had become very painful. Cortisone shots and other medications were not working. Perhaps I was finished as a cellist. I relayed this to Mr Neikrug and in very simple words he said, ‘Raise your elbow and lower your wrist.’ The instruction was so basic but no one had never said that to me before. He had cured a condition that others could not. I had always feared Tchaikovsky’s Rococo Variations and thought that I would never have the technique nor facility to play that piece. At the end of that first lesson, with my head spinning from the introduction of a new bow hold, a cure for the left wrist and countless other things, he said, ‘Oh, start working on the Rococo Variations.’ I said ‘OK.’ As I left the studio I thought, ‘No way!’ But, then I thought – and this is the essence of my experience with him – ‘If he has faith in me, I must have faith in myself.’

Read: George Neikrug: Memories of a legend

Gisela Depkat

Professional cellist – Canada

George Neikrug was a perfect teacher. He treated all his students with the same kindness, care, honesty and respect. After every lesson, we felt empowered to recreate his sometimes magical teachings in the practice room. He inspired us to believe we could master the cello, or really anything we wanted. With endless patience, he never seemed to tire of long hours of teaching. Before three of us from the Detmold class went to compete in Geneva, we each had four hours of lessons a day. From Germany, the Neikrug cello class moved to Oberlin, then to UT-Austin, then to Boston University. By this time, I had started touring as the American representative for Jeunesses Musicales. I would look forward to my lessons in Boston, calling them my 30,000-mile check-ups. My favourite recollection of Professor Neikrug was following the orchestra rehearsal in Geneva, which he attended. Having dropped me off at my hotel, he started backing away, then stopped abruptly. He rolled down his window and called out, ‘And don’t forget: SING!’

Read: Cellist George Neikrug has died

-

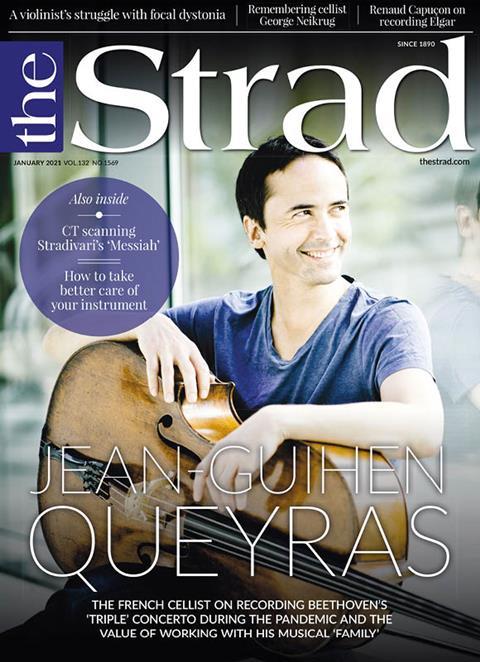

This article was published in the January 2021 Jean-Guihen Queyras issue

The French cellist on recording Beethoven’s ‘Triple’ Concerto during the pandemic and the value of working with his musical ‘family’. Explore all the articles in this issue.Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- French cellist Jean-Guihen Queyras

- CT scanning Stradivari’s ‘Messiah’

- Remembering cello tutor George Neikrug

- Renaud Capuçon on recording Elgar’s Violin Concerto

- How players can take better care of their instrument

- Playing Tchaikovsky with just two left-hand fingers

Read more playing content here

No comments yet