The composer shares how breath is central to this symphonic composition, released on a new album on 8 May 2025, commemorating the 80th anniversary of the end of World War II in Europe

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The requiem is one of the most significant and profound musical forms in Western culture.

The first known requiem was composed in 1470 by the Franco-Flemish composer Johannes Ockeghem. Originally, the requiem was a Christian mass for the dead, dedicated to the memory of the departed. Today, its strict liturgical form is no longer a requirement, and almost every musical genre has drawn on the essence of this lamentation. Still, the requiem offers composers a way to explore the tension between life and death, transience and eternity.

About a year ago, I realised that the only way I could respond to my current sense of powerlessness and horror was through a requiem. I had visited my grandfather in Eisenhüttenstadt, near Berlin. He is 97 years old and the only member of my family who occasionally spoke of the war. On the journey home, I couldn’t stop thinking about the fact that conversations about possible and ongoing wars have once again become part of everyday life—in my circle of friends, my family, and political discourse. I was raised with the humanism of Petrarch and the ideals of the Enlightenment, experienced German reunification, and witnessed the growing together of Europe with the euro. War had seemed unthinkable in Europe—and then it returned. As a species, humanity seems unable to escape this disaster. Images from war zones deeply move me—and out of this feeling, I began composing my requiem.

The only way I could respond to my current sense of powerlessness and horror was through a requiem

When I returned home, I immediately began working on the music and lyrics. The piece is titled Requiem A. The ‘A’ stands for beginning, departure, and especially breath. Breathing is life—and as a metaphor, it plays a central role in both the music and the text. The idea came from my 14-year-old daughter, Ida, with whom I spoke extensively about the requiem. Together, we discovered a beautiful entry in the Grimm Brothers’ dictionary:

’A, the noblest and most original of all sounds, resounding fully from chest and throat, the sound a child produces first and most effortlessly, which most alphabets rightly place at their forefront.’

Before I wrote the music, I searched for a perspective from which to describe grief. But how does one set the essential signposts in such a work? How can one—especially in Germany—approach the subject of guilt? First and foremost, the perspective is key, just as a photographer chooses their vantage point. I myself have never experienced war, but I am most interested in the question: How can one find their way back to life from the powerlessness of disappointment, pain, and grief? After war, this is an almost insurmountable task.

In the first bass aria, the text reads: ’The sun rises from mist or smoke.’ War is only hinted at, never explicitly named. The notion of guilt runs throughout the piece but is never spoken—it appears in imagery. In the Sanctus, for example: “Up we went, hands stained with blood, ashes on our faces.’

Once it became clear that breath would be the central metaphor of the texts, I had to find a musical equivalent.

I found inspiration in the Pythagoreans. They believed the root of nature’s eternal flow lay in the Tetraktys. Fourths, fifths, and octaves form this harmonic foundation—the key to understanding the harmony of the universe.

Thus, Requiem A is built upon fourth and fifth intervals throughout. They form the backbone of the composition across all instrumental groups. They can be clearly heard in the strings at the beginning and end of the bass arias, and also at the start of the Introitus and the Sanctus. Strings, winds, and percussion create the impression of a quiet, sleeping breath that gradually intensifies, culminating in the final movement titled ‘Atem’ (Breath). Even in the choral writing, I repeatedly use parallel fifths to carry the idea of the flow of life into the sound. Upon this foundation, the motifs of grief and loss wrestle with those of breath and life. In the final chorus, the life motifs prevail; grief and powerlessness are woven into the counterpoint and supported by more consonant harmonies.

I envisioned the structure of the requiem like a city—partially destroyed, partially rebuilt. The Kreuzkirche in Dresden, where the piece premiered in February, survived the 1945 bombing, while the surrounding Altmarkt was destroyed. Its layout was preserved, but new buildings were erected. Likewise, Requiem A is based on an old blueprint: the Kyrie and Agnus Dei are, so to speak, preserved monuments, while other parts—like the Sanctus—retain original elements but are supplemented with my own texts, much like the reconstructed Frauenkirche in Dresden. In the traditional seven-part form, Agnus Dei and Kyrie retain their original positions.

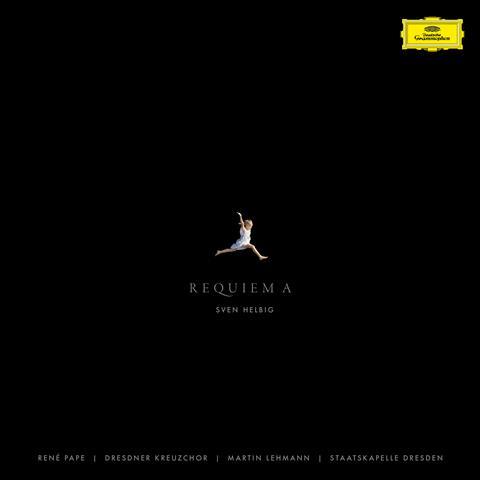

Even on the cover of the Deutsche Grammophon release, the theme of transition from mourning to life continues. I’ve often heard that after the war, the ruins of cities became playgrounds for children. Children have an incredible ability to adapt to new situations and discover something positive within them. I photographed a girl in mid-jump and placed her against a black background. When I showed the image to my longtime friend, Pet Shop Boys singer Neil Tennant, he suggested making the girl much smaller—set against a vast, black backdrop. He said: ’Everything is pitch black, but at the core, there is life.’ I immediately loved the idea. His words even became part of the final chorus, translated into Latin:

’Atra, omnia atrata, sed in nucleo vita est!’ – ’Dark, all is dark—but life resides at the core!’

I also integrate synthesisers into the requiem. With electronic elements, I can generate frequencies that soar above or rumble beneath the choir and orchestra—deep basses and shimmering highs. For me, synthesisers have become mature, autonomous instruments, and I can no longer imagine composing without this sound palette.

The premiere took place on 9 February 2025 at the Dresden Kreuzkirche with extraordinary musicians: the Staatskapelle Dresden, the Dresden Kreuzchor led by Kreuzkantor Martin Lehmann, and bass-baritone René Pape—music-making could hardly be more beautiful or fulfilling.

I look forward to performing this work in historically significant locations this year—including with the Vienna Symphony Orchestra on Vienna’s Heldenplatz, and with the London Contemporary Orchestra in London’s Westminster Hall.

Requiem A is released on 8 May 2025 on Deutsche Grammophon. Sven Helbig’s REQUIEM A celebrates its UK premiere at Central Hall Westminster on 4 October 2025, featuring René Pape, the London Contemporary Orchestra, and four European choirs: https://www.svenhelbig.com/

Watch: Violin engulfed by Reishi mushroom in one-year timelapse

Read: ‘An emotional journey’: Alexander Sitkovetsky on Strauss’ Metamorphosen

Read more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

The number one source for playing and teaching books, guides, CDs, calendars and back issues of the magazine.

In The Best of Technique you’ll discover the top playing tips of the world’s leading string players and teachers. It’s packed full of exercises for students, plus examples from the standard repertoire to show you how to integrate the technique into your playing.

The Strad’s Masterclass series brings together the finest string players with some of the greatest string works ever written. Always one of our most popular sections, Masterclass has been an invaluable aid to aspiring soloists, chamber musicians and string teachers since the 1990s.

The Canada Council of the Arts’ Musical Instrument Bank is 40 years old in 2025. This year’s calendar celebrates some its treasures, including four instruments by Antonio Stradivari and priceless works by Montagnana, Gagliano, Pressenda and David Tecchler.

No comments yet