Nowadays best known for its neo-Gothic castles, this south German town has possibly the oldest lutherie tradition of any in the country. In this extract from the April 2018 issue of The Strad, Thomas Riedmiller traces its beginnings

This is an extract of a longer article in the April 2018 issue of The Strad. To read it in full, download the issue now on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

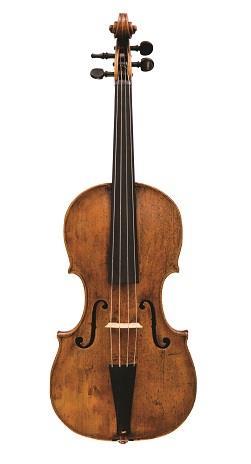

Situated in the far south of Bavaria, surrounded by the foothills of the Alps, the small town of Füssen has possibly the longest tradition of stringed instrument making of any German town. Although its lutherie industry waned in the 19th century while those of Mittenwald and Markneukirchen went from strength to strength, its influence continued through the number of makers who moved to other cities to ply their trade. But the story of making in Füssen stretches for 400 years, from the 15th century onwards, and encompasses elements of art, culture, business and music. The industry served to make this little Alpine town into one of the most prosperous in the region, and also helped to establish trade links with Italian cities such as Venice.

…

In his autobiography, English diplomat Thomas Hoby (1530–66) recounts a journey he made from Augsburg to Venice in 1548 while he was a student at Cambridge. His travels took him through Füssen where he saw ‘Bellies of Lutes made in most perfection and from hense bee sent to Venice and sundrie other places’. Almost a hundred years later, in 1643, a book of engravings by artist Matthäus Merian (1621–87), the Topographia Sueviae, contained an entry on Füssen: apart from geographical information, it includes the sentence ‘Men make good lutes and violins there’ – indicating that the industry was a unique identifier for the town.

From the same era as Hoby’s report, namely 1552, we have the last will and testament of Laux Maler (1485–1552), one of the earliest lute makers whose instruments still survive: it mentions around 1,100 lutes of various sizes, as well as dozens of unfinished instruments, 1,354 lute tops (of which 1,154 had already been given roses and inlays) and four boxes of ribs.

Given the number of finished lutes, they cannot possibly have been made by Laux Maler alone – such a haul would have taken at least 50 years for a single maker to complete. So we can infer that this testament comprises the inventory of a trading house rather than the output of just one atelier. It is evidence of the division of labour in Füssen’s instrument production at the time.

To see the full article by Thomas Riedmiller, download the April 2018 issue of The Strad on desktop computer or via the The Strad App, or buy the print edition

No comments yet