The private residence where some of the legendary players featured in the October issue of The Strad performed is under threat. Nicholas Lane revisits those glorious days – and nights – via first-hand accounts from the time

When read together, the variety of first-hand accounts, Music at Midnight, Overture and Beginners by Eugene Goossens in 1950, My Young Years by Artur Rubinstein published by Jonathan Cape, London, in 1973, Lionel Tertis’s My Viola and I in 1974, each looking in from a different angle, allow us to catch a glimpse of the others. Szymanowski’s collected letters, published in Warsaw 1982, will add another dimension when they are available in English. Each gives us detailed first-hand accounts of these great musicians at work, snapshots eagerly captured, a need that remained even after 60 years had passed, such was the impression these performances left on the authors. These vivid accounts bring the history of 19a to life.

Rubinstein writes in My Young Years: ‘May 1913 passed off like a dream. The nights of music at Edith Grove were inspiring – they were inspiring in the best sense of the word. The company of great musicians dedicated to the purest expression of their art enriched, ennobled, exalted the lives of those present, whether performing or listening.’

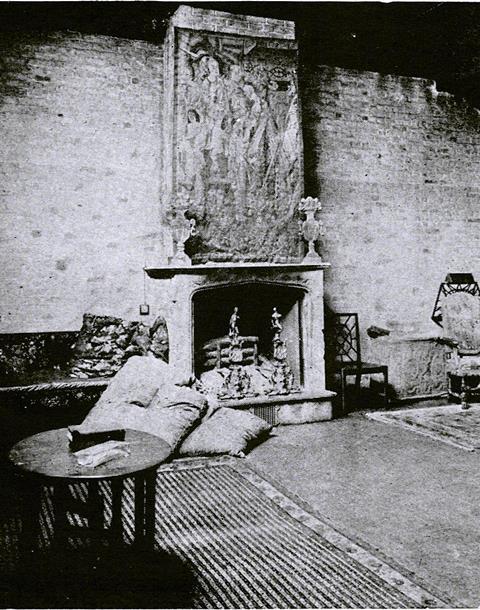

We also have wonderful accounts of the atmosphere of the room and its appearance. Muriel recounts that during the Drapers’ time in Florence from 1909–11, Isadore Braggiotti, with whom Paul was then studying, would host ‘“Pupils’ Concerts” in the vast galleried music room of his villa’. Whether it was her conscious intention to attempt to recreate the setting in miniature at 19a, Muriel does not specify, but a clue may be found in Rubinstein’s description of the interior of 19a, that: ‘the whole gave the impression of the interior of a Florentine palace.’ Was this comment possibly the result of a long-remembered conversation with Muriel about the studio? ‘Miraculously she created out of it a magnificent, spacious, square, noble music room. On one side of the huge fireplace stood the Bechstein concert grand, some music stands, and shelves with music. On the wall opposite was a majestic sofa flanked by two Renaissance tables... The mantle over the fireplace was covered by an old Gothic tapestry. Dark beams crossed the ceiling, and huge candles were posted in prominent places.’ Rubinstein had in fact chosen the piano for the Drapers’ studio.

Rubinstein writes: ‘The night I was about to enter the enchantment of this place, I heard from the entrance door the theme of the second movement of the F major Quartet by Beethoven, the op.59 no1. Nothing more beautiful has ever been written.’

He describes the arrival of Paul Kocha?ski and Zosia: ‘With the beginning of June, when the London season reached its peak, most performing artists would come to the British capital, as all artistic activities on the continent were at rest until the autumn. Paul Kocha?ski was immediately recognised by the Drapers as a full-fledged partner in all musical activities at the studio.’

Rubinstein writes: ‘Music at 19a... entered a new era. Musicians who heard about our reunions begged to be allowed to join them... performers were always welcome, even if they had no chance to perform, but [Muriel] would not tolerate anybody but a few listeners of distinction, mostly men like Sargent, Henry James, or Norman Douglas.’

Rubinstein recalls the meeting of Casals and Tertis at the studio: ‘I remember the night when Rubio brought Casals for the first time to Edith Grove. We were having supper while a quartet of Mozart was being played in the studio. Pablo stood still at the front door and asked suddenly: “Who plays the viola?” He discerned Lionel Tertis’s tone from that long distance. It was a happy meeting for the two great artists. A curious coincidence: both are born on the same day of the same year [1876], and right now, as I am writing this, they are both alive and well at the ripe age of 96.’

‘Paul Kocha?ski and I were very fortunate in that year of 1913 to have made so much chamber music with these giants. Rubio worshipped Casals and always called him Pablissimo. He himself was quite a personality... and could have served as a model for Michelangelo’s statue of Moses.’

‘On that night of Pablo’s first contact with the music room, I heard for the first time the String Quintet with two cellos by Schubert, played with deep inspiration by Thibaud, Paul [Kocha?ski], Tertis, Casals and Rubio. My emotion at hearing it is indescribable.’ (Rubinstein dates Casals’ first visit to 19a to 1913, whereas Goossens’ account has it in the previous year.)

Interestingly, 1913 is believed to be the year that Casals acquired the cello by the Venetian luthier Matteo Goffriller dated 1733 but possibly made around 1700. If so, 19a must have been one of the first places where Casals played it.

‘Thibaud, who had been examining Kocha?ski’s Stradavari, tried a few passages on it and promptly at 4.10am commenced to play the Bach Chaconne. I can’t recall a nobler performance, nor a more atmospheric one. Surrounded by rapt listeners, and seen through the eerie, smokey haze of candles, dawn and fire-light, the superb artist became transfigured, and we were all incredibly moved... On how many similar occasions did we not repeat these feasts! Always there were new faces, and unexpected happenings, as when one night Suggia and Casals took their cellos behind screens and made us guess which of the two were playing.’ Goossens also mentions that Oscar Nedbal and Tivada Nachez played at the studio.

It was while the 19-year-old Goossens was studying violin at the Royal College of Music under Rivard, as well as conducting and composition with Stanford, that he received a message one day in 1912 to go to 19 Edith Grove at 10pm: ‘I had been told that some Americans named Draper were having a chamber music session and needed a viola player. I was ushered into a dining room on arrival and amazed to find Casals, Thibaud, Bauer, Kocha?ski, and Muriel and Paul Draper just finishing dinner... We all went down some narrow stairs into the largest and most sumptuous studio I had ever seen. Built in the back garden of the house, its conspicuous features were a Tudor fireplace surmounted by a Gothic tapestry, an enormous Kien Lung screen behind an equally enormous sofa, a Bechstein piano, huge floor cushions, heavy candelabras, a dozen music stands, and stacks of chamber music.’

Writing at the same time as Rubinstein, but 24 years after Goossens, Tertis remembers the studio slightly differently in My Viola and I (published by Khan & Averill, London, 1974): ‘During the First World War I took part in some of the most delightful chamber music making imaginable. The scene was a cellar in Chelsea, and the meetings lasted as a rule from midnight till daybreak! The audience were guests of an enthusiastic American music lover, Muriel Draper. No public performances could ever have reached such pitch of carefree, rapturous inspiration. There were no rehearsals; the music came fresh, and the executants were no duffers – they included Ysaÿe, Casals, Thibaud, Harold Bauer, Cortot, Kocha?ski (a brilliant Polish violinist), Szymanowski, Arbos, Artur Rubinstein and Albert Sammons. Mrs Draper had built a basement room for music under her two houses (19 and 19a) in Edith Grove, Chelsea. We used to call it “Mrs Draper’s cellar”. Ysaÿe’s word for it was “le cave”... Numerous works were performed, ranging from duets to octets, one in particular stands out in my memory: Brahms’s C minor Piano Quartet, played by Ysaÿe, Casals, Rubinstein and myself. Prodigious, the lusciousness and wealth of sound! Ysaÿe with his great volume of tone and glorious phrasing, Casals playing in the slow movement with divinely pure expression, Rubinstein with his demonical command of the

No comments yet