Royal College of Music professor Rashkovsky offers advice on recreating the spirit of the great playera in this charming piece by the 19th-century virtuoso. Download the score as two PDFs at the bottom of the article

Once popular with 19th-century violinists, Joseph Joachim’s Romance in B flat major (the first piece from Three Pieces op.2 for violin and piano, c.1850) fell into oblivion during the 20th century. Only recently was it deservedly resurrected – when it became a mandatory piece at the Hannover International Violin Competition, an event honouring Joachim.

The piece, dedicated to his composition teacher Moritz Hauptmann, eloquently displays the young Joachim’s artistic maturity and considerable talent as a melodist. Joachim’s collaborator and biographer Andreas Moser wrote: ‘It bears the stamp of simplicity and refinement, the theme being melodious and poetic, while the pianoforte accompaniment shows remarkable independence in the part-writing. It is indeed a little gem, and as it never fails in its effect, has always been a favourite with violinists.’

Joachim, as an advocate of artistic freedom who believed that violinists should use their own fingerings and bowings, provided very few fingerings for the Romance, thus opening up a world of possibilities to the performer. The fingerings I have indicated are the reflection of a mood at a certain moment in time; on a different day, in a different climate, other ideas would see the light of day.

However, I have strived to follow Joachim regarding bowings, which here underline the importance of a long singing line. As players we have become used to changing bowings for practical purposes, but it is important to bear in mind that for violinists of Joachim’s time and earlier the management of a slow bow was a major aspect of their art. Although for the sake of variety I have suggested some flexibility, it is recommended that the student at least attempts to play the original bowings, which are in the piano part, to get a feel for the phrase Joachim had in mind.

As with all short pieces, so much must be said in a limited time. The Romance is full of subtle shadings and shifts from intimate melancholy to impassioned intensity. Each dynamic marking is precious. Here the advice of Joachim’s student Leopold Auer in his 1921 book Violin Playing As I Teach It is invaluable:

The average student pays no attention to the difference between a piano and a pianissimo, to making sharp distinctions between fortes, fortissimos and mezzo-fortes, and above all he ignores the value of the crescendo and diminuendo, preceded by a poco a poco. As a rule he proceeds under the impression that crescendo means ‘louder’, and that diminuendo stands for ‘softer’, whereas these shadings should be carried out by degrees leading up to the fortissimo or down to the pianissimo.

Vibrato needs special mention here. Around the time of Joachim’s death in 1907, vibrato was undergoing a radical change, developing into the continuous form that we take for granted today; however, Joachim viewed it as but a simple ornament to be used with economy and discernment. In their Violinschule (1902–5) Joachim and Moser suggest a particular way of applying vibrato in the Romance, connecting the music with words, as a singer: ‘If… the player wishes to make use of the vibrato in the first bars of the Romance (which, however, he certainly need not do), then it must occur only, like a delicate breath, on the notes under which the syllables 'früh' and 'wie' are placed.’ (In other words on the first crotchet of each bar.)

The modern violinist may make use of the tonal qualities of continuous vibrato, yet with much variety in speed and width, responding to the music’s myriad emotions.

Through an imaginative, resourceful use of fingerings, bowing and vibrato, the interpreter of the Romance ceases to be merely an instrumentalist but becomes a singer and painter, while recreating the qualities that were landmarks of Joachim’s own playing style: nobility and dignity.

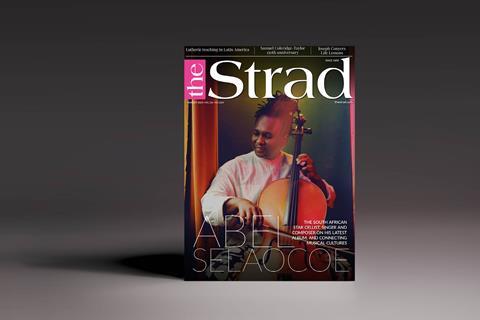

This article was first published in The Strad's August 2007 issue. Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial. To purchase single issues click here.

No comments yet