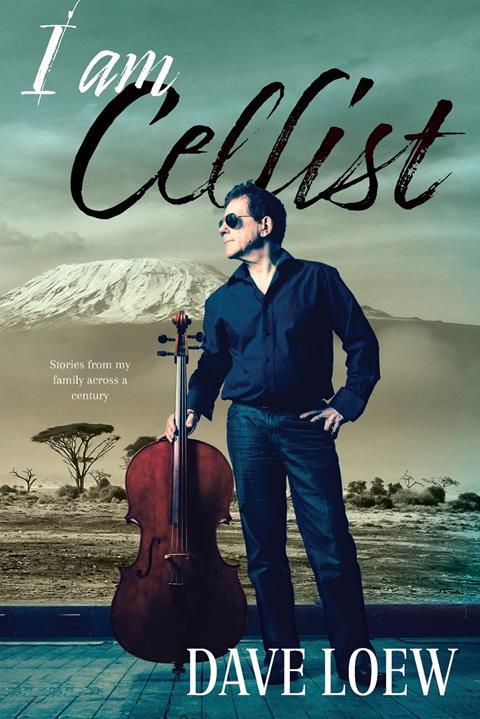

Tully Potter reviews the autobiography of Australia-based cellist Dave Loew

I Am Cellist

Dave Loew

280PP ISBN 9781922527257

Green Hill Publishing £16.99

Dave Loew may well be the world’s most popular cellist. He has sold thousands of albums ranging from Bach through pop songs, show tunes and film melodies to operatic arias. Yet for all his success he has been dogged by depression, about which he is very honest.

Born in Kenya in 1949, Loew started the cello at six and used to play it outdoors, where among his audience were his Ridgeback dog and Simba, an ageing lame lion. Show business ran in the family. His father Jack Filmer, a bandleader and double bassist, and his mother Maria, a former dancer, kept a hotel and diversified into chicken farming.

His first teacher was a Hungarian refugee from the Holocaust – which had swallowed up some of Loew’s family – and amazingly he had a lesson from Raya Garbousova, who was holidaying in Kenya. It was the 1950s, the time of the Mau Mau uprising, and apart from the fear engendered among the white community, young Dave suffered from being bullied at boarding school.

In 1966 the family emigrated to Australia, where the well-known John Painter totally overhauled Loew’s technique – so well that he became principal in the Australian Youth Orchestra. Another influence was violist Robert Pikler, who played with Painter in the Sydney String Quartet. In the Sydney Symphony Orchestra Loew (using his mother’s family name) had his first experience of how one misfit can make life miserable for a newcomer, but in the Melbourne Symphony he was happier.

Finally, after several abortive British expeditions including a teenage spell at school, Loew made it to London in 1977 and became part of the then flourishing freelance scene, playing especially with the LSO. His experiences of recording gigs run by the ‘mafia’ of senior players and fixers, chief among them Sidney Sax, range from humour to horror. He writes warmly about his studies with Christopher Bunting.

Back in Australia, he made his first solo album, Debut, founded his National Arts Orchestra and after many adventures, including another spell in Britain, broke through with his recordings and his own label. He goes into some detail about his love life, including a disastrous marriage, but in fact the chapter ‘My Five Mistresses’ is about his cellos: having played a Vincenzo Sannino instrument, nicknamed Gladys, for years, he now has a modern cello made for him by Kai-Thomas Roth.

The writing style is cliché-ridden and the book’s organisation, or lack of it, is a little confusing. Errors such as ‘Andre Navarre’ and ‘Harry Bletch’ would have been spotted by a good proofreader. But Loew does have a tale to tell, his success despite bouts of bipolar disorder may encourage some colleagues, and there is much to enjoy, not least the many photos.

TULLY POTTER

No comments yet