American cellist Leonard Rose was a consummate performer and pedagogue, whose velvety tone was the result of complete mastery of the bow arm. Oskar Falta explores some of his bowing theories and speaks to former students about his teaching techniques. From November 2020

Explore more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Leonard Rose’s biography reads like an American dream come true. He was born in 1918 in Washington DC to poor Jewish-émigré parents who had fled from imminent pogroms in Belarus (his father) and Ukraine (his mother). Rose spent most of his childhood in Miami, Florida, where he received his first serious cello lessons from Walter Grossman.

After graduating from high school, he studied for one year with his cousin Frank Miller in New York and in 1934 was accepted by the Curtis Institute of Music in Philadelphia to join the class of Felix Salmond (right). Following his studies, Rose served as assistant principal cellist of the NBC Symphony Orchestra under Arturo Toscanini, going on to become principal cellist of the Cleveland Orchestra and finally of the New York Philharmonic, under Artur Rodzinski, Bruno Walter and other prominent conductors of that era.

Early on, Rose became an active pedagogue. From 1946 he was professor at the Juilliard School and in 1951 he joined the faculty of Curtis, succeeding Gregor Piatigorsky. Around that time, he left the New York Philharmonic to pursue the path of a concert artist and dedicate more time to teaching. He embarked on an international career as a soloist and later became a member of the acclaimed Istomin–Stern–Rose Trio.

From 1952 until his demise, Rose’s stage companion was a precious instrument made by Nicolò Amati in 1662 (currently played by Gary Hoffman), one of the few of its kind that was not reduced in size. Rose had a preference for low-tension strings; like most string players of his generation, he started on gut strings, with pure gut for A and D, and silver- or copper-wound gut for G and C. He subsequently switched the two upper strings to an aluminium-wound gut D and a steel A, a set-up he kept for many years. In the later part of his career, he once gravitated towards synthetic core strings.

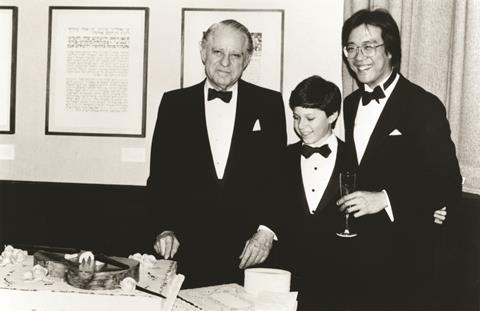

When Rose died in 1984, he left not only a significant number of recordings and edited sheet music bearing a footprint of his own interpretations, but also an extensive teaching legacy. During his tenure at Juilliard (until his death) and at Curtis (1951–62), he taught about 250 students – among them Yo-Yo Ma and the late Lynn Harrell. Other students included numerous future section principals in some of America’s most prominent orchestras and faculty members of renowned conservatoires. It was Rose’s beautiful sound among many other great artistic qualities that drew students from all over the world to join his studio.

The Bow Arm

Rose was aware that use of the bow arm, which he himself mastered to perfection, was a much-neglected aspect of cello technique and believed it was often not very well taught. It therefore comes as no surprise that he made ‘teaching the bow arm’ the trademark of his pedagogy. His former student Selma Gokcen (who teaches the cello at the Guildhall School of Music and Drama in London) recalls: ‘His sound was uniquely resonant and with a velvet sheen, one could say. I can recognise his students from that unique sound quality – that is, those who were with him long enough to absorb the knowledge.’

Along the same lines, Steven Honigberg (cellist in the National Symphony Orchestra in Washington DC and author of the 2010 book Leonard Rose: America’s Golden Age and its First Cellist) reflects: ‘The bow hold and motion of the Rose right arm take years of practice to perfect. They do not come overnight. But once they do, the colours produced on the instrument are as deep as they can be.’

The way Rose played and taught was naturally influenced by his own mentors, as well as by encounters with various violinists. His early teacher Grossman taught him the importance of an ever flexible right thumb. Miller then lowered Rose’s right wrist and instilled in him a technical routine consisting of scales and studies. But the most salient formative influence on Rose was undoubtedly Salmond, an Edwardian English gentleman who had established himself in the US in the early 1920s.

Salmond was a close acquaintance of Elgar, whose Cello Concerto he had premiered while still in England. He was a fine cellist with a distinctive sound and was recognised as England’s foremost cello soloist prior to moving to the US, where he continued giving concerts, becoming one of the New World’s most successful teachers. ‘He had a magnificent sound on the instrument. I think a lot of my sense of sound came from that period,’ wrote Rose about Salmond in his unpublished memoir (quoted in Honigberg’s book).

Salmond possessed a valuable library of cello music, which he later bestowed to Rose, who then edited these works for publication by the International Music Company. They included much of the standard repertoire – such as concertos by Haydn, Saint-Saëns and Dvořák, and sonatas by Brahms, Franck and Shostakovich, to name a few – but also select etudes and orchestral excerpts. Rose’s editions containing his fingerings and bowings might seem outdated nowadays, but generations of students were served well by them and they provide a window into Rose’s personal playing style.

Desmond Hoebig (who teaches the cello at the Shepherd School of Music at Rice University in Houston) remembers Rose saying: ‘Just do my fingerings; they work.’ Hoebig thinks Rose’s editions still provide a good reference for comparison with modern scholarly urtext editions, which are often less driven by the practicalities of performance.

Violin Influence

In the course of his orchestral career, Rose had the chance to observe and analyse the playing of Jascha Heifetz and other violin virtuosos at close quarters directly from the principal’s seat. Nevertheless, it was his meeting with the legendary violin teacher Ivan Galamian that marked a turning point in his approach to pedagogy. In 1952, Galamian invited him to join the faculty of the Meadowmount School of Music, a summer school in the Adirondack Mountains in the north-eastern part of New York State. There, Galamian generously shared his main teaching principles with Rose, who adapted some of them for his own use. One of these principles was the importance of a relaxed bow hold.

Read: Ivan Galamian: hand of steel

Read: Bow hold: Gripping times

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Rose emphasised that the fingers and the thumb should always remain flexible when holding the bow. A thumb that is too straight or curved would cause a tight wrist. As Rose himself stated (in a video available on YouTube, entitled ‘A lesson with Leonard Rose: 1978’, bit.ly/3caqKsm): ‘The thumb with the rest of the hand has to be capable of movement just like a skier’s legs. You know, when he goes over bumps… his knees absorb some of the shocks.’ Indeed, Rose regarded all components involved in sound production – the string, the bow hair and stick, the thumb, the fingers, the wrist, the elbow and the shoulder – as a series of springs. Locking any of these springs would impair the quality of the sound.

Rose’s basic rule of drawing the bow was based on a sensation of pulling on a down bow and pushing on an up bow, reflecting the French terms used for down bow and up bow respectively: tirer (to pull) and pousser (to push). At the beginning of a down stroke, the elbow triggers the pulling motion. Flexible fingers and thumb follow the elbow as the forearm gradually pronates (rotates inwards) while the bow is being ‘pulled’. This action levels the dorsal side of the hand with the forearm as the bow moves.

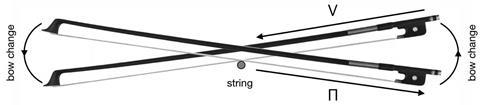

In discussion with the violinist Oscar Shumsky, Rose realised that the bow’s movement across the string is circular rather than straight. Keeping the bow closer to the string below on a down bow and closer to the string above on an up bow creates little circles at the ends of the bow during bow changes. Thus, the bow operates in figures of eight and the connection of two strokes becomes one uninterrupted single action (example 1).

Alongside the figure of eight, Rose taught the ‘paintbrush stroke’ for a smoother change of bow. This stroke – likely to have been borrowed from the analytical violin teacher and doctor Demetrius Constantine Dounis – is executed at the frog, with the arm working as if it were the handle of a brush with the fingers with thumb as its hair; in other words, the arm precedes the flipping movement at the bow change. That, however, is less feasible at the tip, where an increased leverage limits the flexibility of wrist and fingers.

Martelé and Collé

There were two bow strokes that Rose considered the fundamental pillars of a good right-hand technique: martelé and collé. Martelé is a fast, percussive stroke with a sharp initial accent, followed by a release of pressure, as if one were catching the string and then letting it go, while making sure the bow stays on the string. Rose taught the martelé in the upper half of the bow: drawing the bow from the middle to the tip, the arm opens from the elbow joint and in one motion tilts the bow towards the string below while at the same time slants the bow forward, thus creating a triangle between the shoulder, the wrist and the contact point.

At the tip, the bow is at a slight angle with the bridge, so that the tip is more inclined towards the fingerboard and the frog further away from the player. This slightly curved bowing produces a more resonant sound than a perfectly straight stroke. Bowing from the tip, the arm closes, rocking the bow back to its previous position, as if drawing a half-moon. This rocking movement of the bow, simply described as ‘out and down’ and ‘back and up’ by Rose, is a recurring aspect of his art of bowing. ‘Who said there was such a thing as a straight bow?’ stated Rose.

The collé presented by Rose was in fact a small-scale martelé, played at a slow tempo at the frog in separate strokes and only by the fingers, with the same rocking motion of the bow across the strings, starting in the down bow position with curved fingers and alternating between straight fingers on a down bow and bent fingers on an up-bow. It served mainly as an exercise to make the fingers supple and was not meant to sound pretty.

As practice material for the collé, Rose suggested Duport’s Etude no.7 (example 2). Interestingly enough, an almost identical exercise was advocated by Rose’s near contemporary and European counterpart André Navarra – a resemblance that seems more than coincidental. Rose believed that by mastering martelé and collé strokes, a solid foundation for most other bow strokes can be formed.

Teaching Legacy

Rose reflected on the origins of his teaching principles thus: ‘There’s nothing about this that is original; I haven’t made up anything. I’ve just organised it in my own mind, and I think I’ve been smart enough to steal from some pretty good people.’ In spite of this humble confession, it must be noted that a larger portion of Rose’s teaching philosophy was of his own invention and stemmed from the rich, practical, first-hand experience of a world-class performer, as is aptly implied by Eric Wilson (who teaches the cello at the University of British Columbia, Vancouver), once Rose’s protégé:

‘Mr Rose’s approach to teaching was holistic in that musical expression and technique needed to be integrated within the context of a deep and profound relationship to the music. In this sense, his beautifully choreographed gestures contained the elegance and grace required to give a voice to the music. His soul was in his sound and to be in his studio and be enveloped by his glorious playing was an incredible experience.’

One can imagine it wasn’t an easy task for Rose to combine his busy performing and teaching careers. That said, Rose’s success as a teacher would not have been the same without his Juilliard associate (from 1958) Channing Robbins (1922–92). Himself a student of Salmond, and a Cleveland Orchestra colleague of Rose, this humble man – a dark horse – patiently guided the latter’s students during periods of their teacher’s absence and had his share in shaping some of the greatest talents who passed through Rose’s studio.

Rose counts among the most influential string players of the 20th-century American classical music scene. He not only enjoyed a multifaceted career as a performing artist, but also made it his vocation to share his skills and knowledge with younger generations of cellists. Looking back at Rose’s teaching career, his contribution to the rise of American cello pedagogy is striking. Many of his students from Juilliard and Curtis became teachers themselves and have continued to pass on his legacy in the US and abroad – perhaps with their teacher’s noble sound in mind as a lasting example.

Read: Violin Bow Hold: No holds barred

Read: Technique: Speaking with the bow

Discover more Featured Stories like this in The Strad Playing Hub

-

This article was published in the November 2020 Dover Quartet issue

The American ensemble on recording a new Beethoven cycle and inspiring the next generation of chamber musicians. Explore all the articles in this issue. Explore all the articles in this issue

More from this issue…

- The Dover Quartet on Beethoven

- Julie Lyonn Lieberman on teaching different styles

- Italian maker Carlo Bisiach’s US connection

- Frank Peter Zimmermann on recording Martinu

- The teaching methods of cellist Leonard Rose

- The bow makers of Hollywood’s golden age

Read more playing content here

Best of 2022: The Strad Playing Hub

Rediscover your favourite online articles from The Strad’s Playing Hub from the past year

- 1

- 2

- 3

- 4

- 5

- 6

- 7

- 8

Currently

reading

Currently

reading

Leonard Rose: All about the bow

- 10

- 11

No comments yet