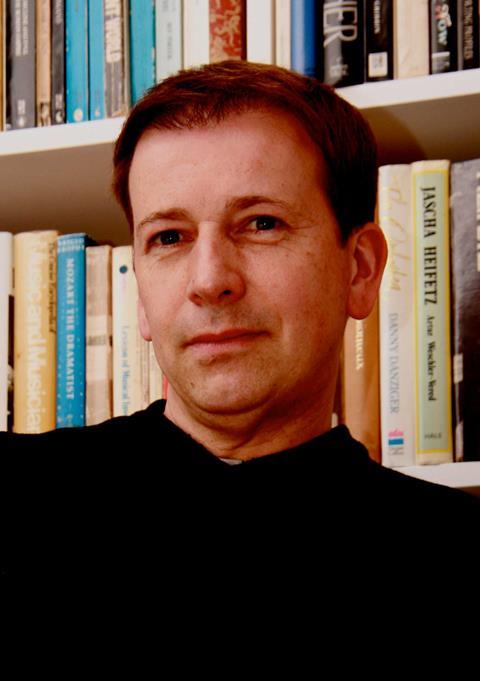

Stephen Bryant, concertmaster of the BBC Symphony Orchestra, considers the difficulties facing string players when it comes to finding an affordable instrument

It’s not just house prices in London that are soaring out of

control – it’s also the cost of stringed instruments. Last year,

the 'Vieuxtemps' Guarneri 'del Gesù' violin of 1741

was sold for more than £9.8 million, making it the most

expensive violin in the world. How can a violinist starting out in

the profession on a modest salary ever dream of affording a decent

violin at these inflated prices?

A sizeable annual increase in the value of a ‘super’ violin makes

it a very appealing option for a company or a billionaire as a

secure investment opportunity, while interest rates on bank savings

remain ridiculously low. As astute financiers have realised, the

price of a historic stringed instrument has rocketed over the past

decade, making it even more impossible for violinists and cellists

to enter the market. More and more of these priceless instruments

now lie in the hands of investors rather than musicians. Finding

the right instrument has never been more of a challenge – and

unsurprisingly, banks are not jumping in to offer six-figure loans

to freelancers with irregular incomes.

As a student I discovered what happens to these violins bought as

investments, when I was invited by a wealthy collector to try his

instruments. In the basement of a Mayfair mansion I entered a

walk-in security vault and was greeted by an exceptionally valuable

array of instruments, including a Strad, Guarneri and Amati. The

instruments were amazing to play. The Strad seemed to vibrate on

its own and the Guarneri just screamed when I played the E string,

it was so powerful. After I had played them for 15 minutes, the

violins were returned to the safe for the next rare outing. At

least with an expensive painting you can hang it on a wall in your

house to admire it and share it with your friends, but a violin in

a safe remains unheard and ‘mute’.

Before I became concertmaster of the BBC Symphony Orchestra in

1994, I was playing a Santo Serafin, on loan from my previous

orchestra. The day I resigned, I had to give the violin back.

Thankfully I had the good fortune to meet Nigel Brown, founder of

the Stradivari Trust, who helped me to purchase an 1831 Pressenda,

now worth £320,000. Nigel set up a long-term trust for me, backed

by a syndicate of investors who were not motivated solely by

financial considerations but wanted to help a musician – in this

case, me. Over a period of 15 years, this enabled me to buy back

the instrument off the trust, as and when I could. There was no way

that I could have afforded to do this with a loan from the bank:

the payments would have been so punitive with the rate of

interest.

This Pressenda – only the third instrument I tried at the dealer’s

– has a distinct personality of its own. When I put bow to string,

it seems like the violin is talking and there are all sorts of

possibilities to make it speak even more. I know I am one of the

lucky few. I see a lot of young musicians who have decided to stick

with a standard instrument, rather than invest in a new one because

they can’t afford it. As a teacher, it is frustrating to

observe.

At the other end of the spectrum, a schoolchild starting to learn a

stringed instrument will need parents with resources. Not only is

there the cost of weekly lessons, but a basic violin costs around

£200. Fortunately there are music charities, such as London Music

Masters (LMM), that are helping to fill the gap in government

provision, to enable every child in three inner-city primary

schools in London to learn an instrument – loaning the violins

(aided by LMM's Lost & Sound campaign) and providing two hours

of tuition a week.

With the power to enrich lives, music and the arts have a crucial

role in our society, so it is important that young people have the

opportunity to express themselves creatively. Giving a child an

instrument is a vital first step. But it’s just as important that

the ‘super violins’ stay in the hands of musicians, and not become

a commodity to be seen and not heard.

Stephen Bryant will be taking part in a panel discussion on the

subject: 'Is there a moral obligation to make string instruments

available to all?' taking place at 4pm on 24 March at the

Lansdowne

Club in Mayfair, London. The talk will be at the Amati

Exhibition, in advance of Amati’s next online auction.

Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial. To purchase back issues click here.

No comments yet