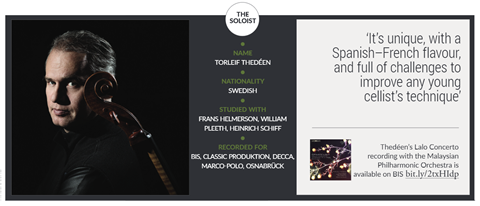

Cellist Torleif Thedéen discusses how to give a rhythmic, characterful performance of the first movement of this often-neglected work

Explore more Masterclasses like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

The Lalo Cello Concerto is frequently overlooked, and it can be difficult to persuade students to play it. It’s a piece that was performed more often in the 1940s and 50s, by cellists such as Pablo Casals and Pierre Fournier, at a time when there weren’t as many cello concertos to choose from. That was before Rostropovich came along and inspired newworks by Shostakovich, Prokofiev and Britten, and then composers like Lalo and Saint-Saëns were pushed aside.

Many cellists prefer to study later works such as the Elgar or Dvořák concertos, but I love the Lalo and I think it is definitely something to push for. The first time I heard it was in Stockholm as a child, with Fournier and the Stockholm Philharmonic, and it made a wonderful impression on me. It’s unique, with a Spanish–French flavour, and full of challenges to improve any young cellist’s technique.

Click here to view the sheet music for this work in our digital edition

Orchestration and projection

When I first played the Lalo Concerto, I thought it was idiomatically written for the cello: it felt wonderful, for example, to play on a low string and then up the A string for the thematic motif. That was until I played it with an orchestra for the first time! The solo part is often in a difficult, low register for the cello, and the orchestration is quite bombastic, so if the orchestral parts aren’t carefully voiced – just as a pianist might bring out certain notes in a chord – they will be overpowering. It is a challenge, for instance, for the soloist to respond to the heroic orchestral introduction when the first solo entry in bar 9 is so low. If it had been written on the A string, it would be easier for soloists to match the orchestra’s sound. In a small room, the cello C string might be more powerful than the A, but with an orchestra in a hall, higher and more penetrating registers help the sound to carry.

Often this piece is played too heroically throughout: cellists feel as though they should perform it as loudly as possible to compete with the orchestra, and they do not bring out the contrasting moods. This is a mistake: instead, they should work closely with the conductor to find the right balance, to give the music room to sing. It’s a piece that demands sonority. Without that resonance it can sound like a chopping contest, and the opening will feel like a fight in the mud! Use a generous amount of weight, bow contact and vibrato to make sure that the tone is full, round and not at all edgy.

Interpretation and character

If I look into the historical background of a piece, I tend to do it a long time after I’ve learnt the notes. I want the music to speak to me first, to find a communication point between the composition and myself. Once that has clicked, I will look more into the background. Above all, this helps me to play organically, and that is important. If there is a ritardando, for example, play it logically, as though the music is a rubber band that is being stretched, then released back to its original shape – keep the original tempo in mind, and be able to return to it. Try not to do unnatural things with the music. Just find its natural flow, character and beauty.

Lalo likes to alternate moods and characters, going back and forth between different musical ‘courses’, and it’s important to highlight these as we play. The opening character, for example, is almost aggressive; but that feeling vanishes in bar 14, when the mood becomes lyrical and calm for two bars. In bar 16, the original character returns. Another example is from the Allegro maestoso in bar 23: here the music is rhythmical and stringent, but in bar 27 we have to play cantabile before returning to the rhythmic theme in bar 31. Even in the cantabile passages there is always a sense of foreboding bubbling away underneath.

Read: Masterclass: Johannes Moser on Brahms Cello Sonata no.1 op.38

Read: Masterclass: Alban Gerhardt on Saint-Saëns Cello Concerto no.1, part 2

Discover more Masterclasses like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

Rhythm and articulation

In many ways this is a Classical concerto and it should be treated as such: play it nobly, with clear articulation to avoid all the flavours combining into one indigestible sauce. This also means that you need to be rhythmical, to give the musical character the right edge. The last semiquavers in the Allegro maestoso (bar 23) and in the second subject (bar 59), for example, are an important feature throughout the movement. Think of them as part of the movement’s spice. They give it shape and character: imagine someone holding their head with pride when you play them. That feeling should continue even when the passage becomes cantabile and beautiful.

The appassionato of bar 78 is the real climax. Again, highlight the semiquaver motif to underline the overall character. I also think it’s important to follow Lalo’s parlando bowing, where he slurs one semiquaver and follows it with two separate bows and one big slur, as in bars 101, 103 and 106. This contributes to the structure and character of the piece.

Before you play the ad libitum at the beginning of the movement, first play the phrase as it is written, in tempo. You should familiarise yourself with the rhythm and shape of the original phrase before you start to be free, or you will be improvising instead! React to the original; make sure you give your phrase the right shape, and know where your freedom comes from. By observing the fermatas, playing the a tempos with conviction and adding a personal touch to the ad libitum bars, you should create the right effect. Remember that the a tempo bars are tied to the fourth-beat chords in the orchestra score, so they have to be in strict time.

From bar 111, and from bar 211 until the end, you will need fast, strong fingers to articulate properly in the lower registers. The music should be loud and fast, with direction, drive and clarity – especially from bars 217 and 227.

Click here to view the sheet music for this work in our digital edition

INTERVIEW BY PAULINE HARDING

Read: Testing a copy of a Rostropovich cello

Read: Masterclass: Natalie Clein on Haydn Cello Concerto in D major

Discover more Masterclasses like this in The Strad Playing Hub

Read more premium content for subscribers here

No comments yet