- News

- For Subscribers

- Student Hub

- Playing Hub

- Podcast

- Lutherie

- Magazine

- Magazine archive

- Whether you're a player, maker, teacher or enthusiast, you'll find ideas and inspiration from leading artists, teachers and luthiers in our archive which features every issue published since January 2010 - available exclusively to subscribers. View the archive.

- Jobs

- Shop

- Directory

- Contact us

- Subscribe

- Competitions

- Reviews

- Debate

- Artists

- Accessories

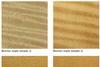

Chinese Tonewoods: Interesting Times

For luthiers worldwide, European wood is still viewed as the best for making stringed instruments – even though China’s forests are filled with high-quality spruce and maple. Xue Peng presents the results of a study comparing the tonewoods of China and Europe, with some startling conclusions

Traditionally, the tonewoods used for violin making have always come from Europe. The climate and geography of the Northern Italian Alps are ideal for growing spruce that has uniform texture, fine grain, clear white colouring and excellent acoustic properties. The abundance of this wood provided optimal conditions for violin making to flourish in Italy during the 16th and 17th centuries, also allowing for experimentation leading to the rapid development of stringed instruments. The voices of the old Italian violins owe their peerlessly beautiful timbre to this wood.

Violin making in China began in the 1930s. At this time there were no professional tonewood suppliers, nor specialist tool manufacturers as there are now. Consequently there was a scarcity of tools and materials, yet under these difficult conditions, the pioneers of Chinese violin making sourced tools and wood from abroad and produced violins that are impressive even by today’s standards. Alongside the rapid rise of the Chinese violin making industry, there was a drive to popularise the instrument across the country, which led the pioneer generation of makers to seek out domestic supplies of tonewood. From the 1950s onwards, their unremitting efforts led to large quantities of spruce from northeast China being used to make training- and conservatoire-level instruments. The craftsmanship embodied in some of these works is outstanding, and helped to inspire and cultivate generations of world-class Chinese string players. In my opinion, of course the materials used to make these instruments is important, but the more significant factor is for the luthier to be able to adjust the making process in order to suit the nature of the different woods being used. If this is possible, it will result in a better instrument.

Already subscribed? Please sign in

Subscribe to continue reading…

We’re delighted that you are enjoying our website. For a limited period, you can try an online subscription to The Strad completely free of charge.

* Issues and supplements are available as both print and digital editions. Online subscribers will only receive access to the digital versions.