String makers receive all kinds of questions from players about their products. Chloe Cutts explores their responses to the most common queries

The websites of leading string brands often include a long list of frequently asked questions (FAQs). These requests from players for guidance and information address fundamental string-related issues: How do I find my ideal strings? What sets different strings apart? How often should I change my strings? How does string tension affect sound and response? What are the characteristics of the different core materials? What’s the best way to clean my strings? How can I extend the life of my strings? Why do strings matter?

The last of these questions comes from US string maker D’Addario’s orchestral strings FAQ menu, under ‘String Basics’, and has the following reply: ‘Changing or upgrading your strings can be one of the easiest and most cost-effective ways to improve the sound and response of your instrument. Correspondingly, it can be very difficult to make an acceptable sound with the use of old or cheaply made strings.’

Common sense, you might say, but violinist Lyris Hung, D’Addario’s orchestral strings product manager, points out that the average string player spends far more time and effort researching and trying out instruments and bows than they do new strings. On the face of it this would seem to make sense: a new instrument is a far bigger investment financially; likewise a new bow. ‘And yet, strings are every bit as integral to the creation of sound – and the quality of that sound – as the instrument, bow and player,’ says Hung. String players who have honed their skills for decades might nevertheless have virtually no knowledge of how their strings are constructed, or how they function, or the best way to care for them. ‘Most people haven’t the faintest idea what makes different strings sound different,’ Hung continues. ‘I therefore always encourage players to use the same process when choosing strings as when selecting a new instrument: try different strings in different playing situations and in different environments, and ask someone to listen to you.’

String makers are often contacted by players who have been using the same type of strings for years, typically from the time their instrument was set up after they acquired it. Having decided to experiment with something different, they find themselves faced with a bewildering variety of string types across the different brands. ‘In this case I ask them to think about their playing in an analytical way, separating out bow response, tone production and different playing scenarios,’ says Hung. ‘I ask: do you have to put in a lot of effort when you bow? Would you like to put in less effort? Would you like a brighter or darker sound, or to blend more easily? These questions are designed to separate the player’s emotions from the sound they’re creating.

From there, I look at the strings they’re currently using, and their set-up. If, for example, they want to project more in ensemble playing, and they’re currently using a dark or warm string, I will make a recommendation in terms of brightness or loudness.’ Despite all the obvious advantages, the majority of string players do not experiment in a formal and extensive way when choosing strings. With this in mind, Bernard Maillot, president of French strings company Savarez, advises players first to identify the problems with their current strings, and then seek advice. ‘Is the problem due to the quality of the string or another reason?’ he asks. ‘If the string is the problem then a luthier will be able to give some advice once they get to know the musician and the instrument.’ Maillot also suggests speaking to other musicians about their strings, and to string manufacturers at trade shows and festivals. ‘In this case the player might also get a free sample to test,’ he adds.

For string players looking for a general guide to what sets different string types apart, Viennese string maker Thomastik- Infeld’s Alphayue microsite offers the following: ‘The simplest difference lies in the different core and winding materials as well as the varying string tensions. The core defines the string’s basic characteristic, while the material used for winding affects the diameter, for example, and thus has an influence on the response of the string.’ The text goes on to say that production methods and unique materials between the core and winding will further affect sound and response.

Franz Klanner, director of engineering and technology at Thomastik-Infeld, says: ‘When people ask for advice on what strings they should choose, I first ask what instrument they have and what type of music they play. Many of our customers play country and western music, and for them we recommend steel-core strings, whereas for classical playing we recommend synthetic. For gypsy music, which has a lot of plucked pizzicato and staccato playing, we suggest a mixture of steel and synthetic core.’ So, what are the main differences between steel and synthetic cores?

‘The construction of a string is complex, but the nature of the core determines a certain kind of sound’ – Bernard Maillot, Savarez

‘Steel-core strings last much longer than synthetic,’ Klanner replies. ‘They have a faster bow response and are very quick to tune, but the sound quality is not as good as synthetic. Synthetic strings have a slower response than steel, but allow you to generate far more colours with your left and right hands. With both steel and synthetic you can achieve the same dynamic spectrum, but to reach the same volume you must, with synthetic, bow with more velocity and with steel apply more bow pressure.’

Thomastik-Infeld introduced synthetic-core strings in the 1960s as a more reliable and affordable alternative to gut-core strings. ‘This was the first goal when we invented the Dominant string in 1969: to copy the good qualities of gut-core strings while avoiding the problems, including no tuning stability,’ says Klanner. ‘On gut it would take two weeks to reach tuning stability, which is useless if you have a concert in the next two or three days.’

A guide to the different core materials, from gut to advanced synthetic, can be found on the Pirastro website, under Services – Core Materials. There are details on the history, properties, sound, construction and purposes of each type, plus which string players they are commonly used by. In terms of sound differences, Hung explains that gut has the highest level of natural damping, and so the warmest foundation or ‘footprint’. ‘Gut also has the most rich and complex footprint, but doesn’t tend to have a bright sound,’ she says. ‘Steel is the opposite: inherent brightness with the lowest amount of damping, but not a lot of complexity. Synthetics are like plastics – they live somewhere between gut and steel and are quite customisable.’

‘The construction of a string is complex, but the nature of the core determines a certain kind of sound,’ says Maillot. ‘For example, a gut core has a warmer sound, whereas nylon offers more high overtones and a cooler sound. Different nylons and the different treatment they receive have varying impacts on the harmonic spectrum and the sound characteristics. Density of sound, response and projection depend on the core material too. The choice is rather personal and may depend on the instrument being clearer or darker, old or new.’

‘I would advise players wanting to audition new strings to try medium tension first, then progress to other tensions’ – Lyris Hung, D’Addario

When it comes to the suitability of certain instruments for specific strings, Klanner says the main concern is for the welfare of old valuable instruments. ‘Normally, steel-core strings have a much higher tension, which is why we don’t recommend entirely steel-core strings on these instruments,’ he explains. ‘For example, violinists from the Russian school frequently use steel A strings to create more volume, whereas in the West it tends to be a steel E string. Orchestral players mainly use synthetic, but again steel-core strings are also used – on the viola the A and on the violin the E.

We have a lot of players of extremely valuable antique instruments, such as a Stradivari or Guarneri “del Gesù”, working in orchestras and using our student-level synthetic strings, which have a certain metallic sound, with more bow noise, which these instruments need because they have lost this quality over the centuries.’ Understanding string tension can help players protect their instrument and improve the way it performs. But what is string tension? Thomastik-Infeld’s Alphayue page explains: ‘The string’s tension defines the force required to tune it to the keynote at a certain scale length. If a string sounds rather nasal, this can indicate the string not having sufficient tension. If a string sounds too dark, the instrument might be under too much tension.’ To the question of what exactly gives a string its tension,

D’Addario’s ‘String Basics’ page replies: ‘It is determined by the amount of mass [material] wound on the string, the frequency of vibration, and string length. String tension affects the response, playability and sound of a string.’

The story of string tension is rather more complicated and technical, as the D’Addario page goes on to explain. But on an introductory level it is worth knowing that for any fixed playing length and desired pitch, adding mass to a string increases its tension, which in turn affects the response, playability and sound. Adding mass to the string also affects how the instrument behaves. ‘It increases vibrational activity and causes your instrument to move more, which creates more volume,’ explains Hung. ‘So on a basic level, more tension equals more volume. I would advise players wanting to audition new strings to try medium tension first, then progress to other tensions. That way they learn how their instrument reacts to strings of different tensions.’

Many string makers offer string lines in multiple tensions – low, medium and high – and there is general agreement on the wisdom of starting with medium tension (although as Thomastik-Infeld points out, definitions of ‘medium’ may differ from one maker to another, ‘so it’s important to check the tension values in the catalogue’). But not all manufacturers believe high tension is necessary. Chinese string maker ForTune Strings produces all its string ranges in medium tension only. ‘The question we get asked most is about correct tension,’ says ForTune’s marketing manager Jordi Palau. ‘The tendency with many string manufacturers is to increase tension in order to increase volume. Our way is different: we aim to produce the best sound with never more than medium tension, and we have developed new combinations of materials to achieve this. For old instruments this is very important.

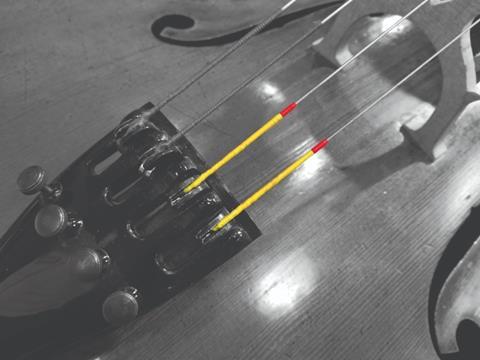

Players, particularly professionals who play with a lot of energy, are surprised to discover that our strings produce such a rich, strong sound.’ String makers are frequently asked how to restring an instrument correctly, to which the most fail-safe advice they offer is to ask a professional luthier to do it for you. For those who prefer to restring their instrument themselves, there is advice on Pirastro’s website, under Services – Advice and Tips, including how to safeguard your instrument from sudden changes in tension by changing strings one at a time (which will also prevent the bridge and soundpost from falling over). The page cautions that once strung, each string loses tension unequally: ‘You should therefore continuously ensure to keep each string tuned to the correct pitch.’ The FAQ tab on Thomastik-Infeld’s homepage also has tips on restringing, including recommended distances between the tailpiece and the bridge, and the height of the string above the fingerboard, plus how to prepare your instrument for stringing in order to reduce the risk of string breakage. D’Addario’s YouTube channel, ‘D’Addario Core’, features video tutorials on aspects of string care and maintenance, including instrument restringing.

Once your instrument has been successfully set up with new strings, how often should you change them? The answer to this frequently asked question has several determinants, including how you play, how much you play, and how well you care for the strings. A professional string player rehearsing intensively every day is obviously going to get through strings faster than someone practising only in their spare time. ‘The time a string lasts depends mainly on the musician,’ says Maillot. ‘Professionals will change their strings more often than amateurs, and some players love the sound of new strings and change their strings according to the number of concerts they play.’ He adds that players should change a string ‘when the sound starts to become poor or foggy, and the string is difficult to play and tune’.

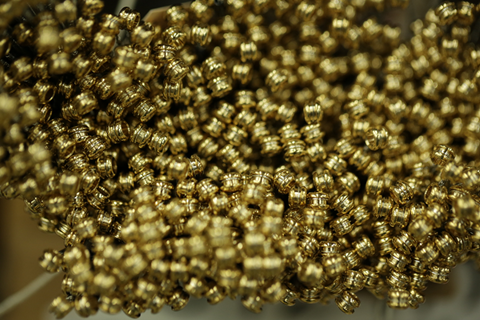

Warchal Strings has published detailed, illustrated guides on a range of string subjects on its website (Support ‒ FAQ), including string wear and corrosion, string care and cleaning, and how often a Warchal string should be replaced. The guide, entitled ‘The Lifespan of Strings (Wear and Corrosion)’, explains that the most significant factors determining replacement intervals are mechanical wear, contamination and corrosion ‘and these very much depend on how the string is handled and played’. Macro photographs reveal the complexity of a string’s open construction, and before-and-after shots show the effects of contaminants – ‘perspiration, salt, fatty acids and all kinds of dirt, dust and dead skin’ – which penetrate the winding and make cleaning ‘much less effective than one would assume’.

‘A string’s construction is quite complex and it gets affected by penetration of all kinds of pollution during its lifetime,’ the Warchal guide explains. ‘The construction of wound strings cannot be sealed. The winding has to be open in order to allow the string to vibrate freely. Once the string is contaminated, you unfortunately can’t wash the dirt out.’

‘Strings often have a high metal content – a steel core, for example, with aluminium, nickel, silver and other types of metals on the outside,’ says Hung. ‘Most of these metals are not corrosion resistant, so they are susceptible to corrosive elements from humidity, air pollution (which can be acidic), and contaminants from the player’s fingers – sweat and oil from our skin, which gather on the string surface, and then, because they are liquids, seep inside the strings and start the corrosion process from the inside.’

Preventative measures such as washing hands regularly before playing, protecting the strings from extreme temperature changes, humidity and air pollution, and applying rosin sparingly are generally recommended, as is removal of rosin build-up by cleaning your strings after every use using a clean, dry, lint-free soft cloth. Several string maker websites have published advice on string care and cleaning, the most detailed being Warchal Strings’ guide on removing rosin build-up, which shows with macro photography the results of cleaning strings with liquid solvents and fine-grade steel wool. Opinions on how best to clean strings vary, and, as this article shows, there are many variables that can inform decisions on any aspect of string selection and maintenance. The best course of action is to research thoroughly, ask the experts, and be prepared to experiment a little – you might just find your perfect set of strings.

No comments yet