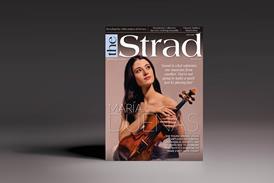

Alena Baeva, who won the Wieniawski Violin Competition aged 16 in 2001, writes about her love for one of the lesser known gems of the violin repertoire

The concertos I am most often asked to perform are the likes of Tchaikovsky, Bruch, and Mendelssohn. Tchaikovsky is the most popular request: Vladimir Jurowski asked me to perform this concerto for my London debut with the London Philharmonic Orchestra on 5 December this winter. Occasionally I get more unusual requests such as Grażyna Bacewicz’s Concerto no.7, which I performed at the Lincoln Center last year.

I am delighted that there is so much fantastic music still to learn that I never had the chance to discover as a student. This year’s addition to my repertoire is Mieczysław Karłowicz’s concerto. There’s such a thrill in performing something that is lesser known: sometimes you have to search for an orchestral score in the orchestra’s libraries, and you don’t have a clear audial impression of a piece in your head – which is definitely an advantage for creating a new interpretation!

I first came across Karłowicz’s concerto in a masterclass seven years ago, where a young violinist played it for me. The music immediately grabbed me, and I was intrigued: such a brilliant, captivating piece, featuring the best of possibilities available to the violin under the Romantic tradition. I asked Mikhail Pletnev about the concerto, and he confirmed that he enjoyed playing much of Karłowicz’s music, including his wonderful symphonic poems. I therefore suggested to my agent that I would be very happy to perform the concerto, and – after a few years – I have now received two engagements to perform it in close succession – one in Warsaw last month, and the other in Katowice this coming Monday 1 October. This year it is especially relevant in light of celebrating 100 years of Polish Independence.

In Poland, Karłowicz is well known, but outside his native country his name is almost unrecognisable. This is without doubt should have been different, but a tragic accident occurred – Karłowicz died in an avalanche at the age of just 32. He went on to gain recognition and praise as as one of the great young Polish composers, but Polish culture lost a great man who had very broad interests: Karłowicz was a keen photographer, mountaineer, writer, collector of interesting historical and musical valuables (including a number of Chopin’s letters), as well as being an accomplished violinist.

Karłowicz was just 26 when he wrote this fresh and truly Romantic concerto. His writing highlights Germanic rather than Slavonic influences: you can hear rich but transparent orchestral writing inspired by Richard Strauss, and also Slavonic harmonies – but no folk tunes in this piece, which was quite unusual for mainstream Eastern European composers at the time. There is a short orchestral introduction, and the violin then takes the stage with monumental massive chords played solo, thus introducing the main theme. The second movement is lyrical – somehow naïve, melancholic, connected with his cultural roots – and the Finale is virtuoso, with extremely fast tempos, light and joyful.

The piece was dedicated to Karłowicz’s former violin teacher, Stanisław Barcewicz, who gave the premiere in Berlin with the Berlin Philharmonic under the composer’s own baton. You can hear this dedication in the concerto, with its distinctive double, triple, and quadruple stopping throughout the concerto, bearing the dedicatee’s signature style alongside his singing tone. Barcewicz had also studied composition with Tchaikovsky in Moscow, and Tchaikovsky’s presence hovers over the concerto, not least in the opening horn motif from Tchaikovsky’s Piano Concerto – in the Karłowicz concerto, it is heard in reverse.

The violin part is very technically challenging, and takes longer to learn than most concertos, but it gets easier with time. It is thrilling to be stretched beyond my comfort zone – other tricky pieces such as Dvořák or Prokofiev second concerto will feel easier now! In this concerto, there is a classical battle between orchestra and soloist, but the orchestra is not the mere accompaniment – it has a very rewarding role, and the violin shines above and dazzles with real warmth and brilliance.

Compared to my beloved Richard Strauss Violin Concerto op.8, it sounds more free and fresh – clearly written 20 years later. I can still remember the first time I heard the concerto at that masterclass – the first impression is so clearly stamped on my mind. I have tried to keep that first memory pure, although I know that I myself have changed: it now feels more connected to Wieniawski than I had thought.

Despite notable recordings by Tasmin Little, Nigel Kennedy, Konstantin Kulka, and Agata Szymczewska, Karłowicz’s Violin Concerto has never really caught on outside of Poland. I feel honoured to have been asked to champion it in its native country – and I really hope it catches on elsewhere.

Alena Baeva makes her debut with the London Philharmonic Orchestra on 5 December, performing Tchaikovsky’s Violin Concerto, before returning to the UK in June 2019 to explore the roots of Schumann’s Violin Concerto with the Oxford Philharmonic in a concert narrated by author Jessica Duchen

No comments yet