For the US cellist, the singing qualities and narrative drive of Bloch’s Schelomo bring evocative memories and spiritual uplift. From the January 2017 issue

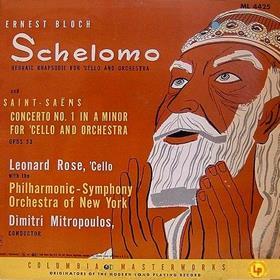

I first heard Ernest Bloch’s Schelomo when I was eleven years old. I was studying Saint-Saëns’s First Cello Concerto and bought Leonard Rose’s 1951 recording with the Philharmonic-Symphony Orchestra of New York under Dimitri Mitropoulos. Schelomo was on the B side and I was blown away from the very first note. It made me cry in its yearning, poignant moments, and it could make me jump with anger and ferocity in the big tuttis. I couldn’t sit still while I was listening to it – it forced me to stand up and walk around while it was playing, or to bow my head in utter despair.

Bloch wrote Schelomo to express his ideas about Jewish music, and many of the people that have made an impact on my life have been Jewish. The year after I first heard it I began studying with Lev Aronson, who was a Holocaust survivor, and for whom Schelomo was a very personal work.

When I was older, I wrote to Rose to say how deeply his recording had affected me and that I wished I could play it like that. He wrote back a very warm letter to say that I should be able to play it brilliantly, because I clearly understood it so well! I went on to study with him at Juilliard. I also worked with Orlando Cole at the Curtis Institute, and he recalled how difficult it had been for his colleague Felix Salmond to learn it – it was written in a too-modern musical language as far as Salmond was concerned.

I understood that to play this piece properly I had to have an understanding of Jewish music myself – Bloch said that the Jewish soul was a living thing inhabiting all his music, and particularly Schelomo because of its great sense of drama. In fact, Pablo Casals avoided performing the piece because he considered it ‘too Jewish’ for him to be able to play properly, even though he played Bruch’s Kol nidrei.

So I studied cantorial singing and got to know more about Judaism, but I didn’t perform Schelomo in concert until many years after I’d started learning it, and it took me a further ten years to be fully confident in my interpretation, and feel it was legitimate. In 2011 I went one step further, and converted to Judaism myself.

While I was principal cellist of the Cleveland Orchestra, I played Schelomo several times under George Szell’s baton. The orchestra played it very delicately but Szell never really let the piece fly. He would re-mark every part so that the balance was exactly the way he’d want it – but I felt I was playing in a ‘mezzo piano–mezzo forte’ orchestra. There was also the fact that Bloch had a very definite idea of how it should be played – it’s one of the most heavily marked scores in the repertoire, where some notes have three indications as to how they must be played. For these reasons, it was a long time before I felt able to play it with freedom in the solo part.

What was important for me was to bring out the sense of drama and the stage. The best pieces for cello always have a feeling of the interaction of opposing forces, and there’s an element of recitative, in that the solo cello will have a theme that’s echoed by the orchestra.

Schelomo also gives full rein to the singing nature of all the cello’s registers – Bloch originally conceived it as a vocal work, and the cello is meant to represent the voice of King Solomon. It needs to have a voice like Marlon Brando’s in The Godfather – quietly spoken but filled with an underlying power that it needs to communicate to the orchestra.

My advice to a student practising Schelomo would be: go to synagogues to hear the melodies that inspired Bloch and other composers; and try to meet with European Jewish families so that you can understand the interaction of the people and the importance of the family unit. So much has to do with the type of expression and emotionalism that is part and parcel of Jewish life.

This article was first published in the January 2017 issue of The Strad

INTERVIEW BY CHRISTIAN LLOYD

No comments yet