The orchestra is to host a free exhibition on the Polish violinist in February and March

The foyer of the Berlin Philharmonic's Philharmonie is to play host to a free exhibition on former concertmaster Szymon Goldberg from 2 February to 16 March 2014, including documents, photographs, personal recollections and a listening station. Tully Potter pays tribute to the Polish violinist below:

Eine leise, kleine, aber wahre Stimme

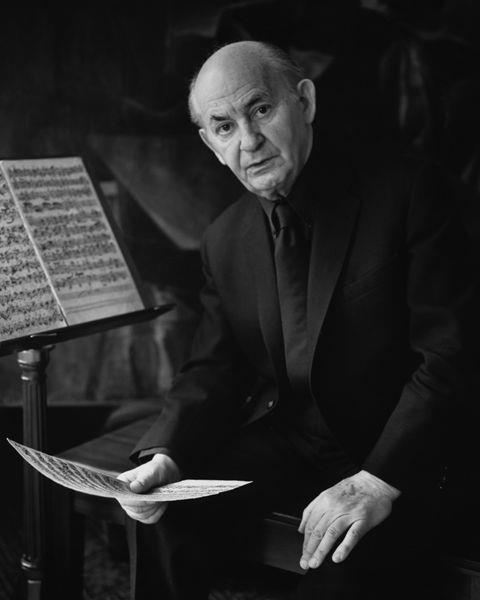

Among the great violinists of the 20th century, Szymon Goldberg (pictured) was a still, small voice. But a true voice. He was not a towering platform personality such as a Heifetz, a Kreisler, a Busch, a Huberman or a Menuhin. His natural environment was chamber music and although he could step forward to play any of the great concertos, his preferred composers were Bach and Mozart: to their music he brought a poise and a beauty of tone that seemed like perfection. Indeed he was the finest Mozart violinist of his time, with the feline grace essential for the violin sonatas, the concertos and the Sinfonia concertante.

Goldberg was Polish, born into a large, happy family on 1 June 1909 in W?oc?awek, north-west of Warsaw. He was given a start on the violin by Henryk Czaplinski, a pupil of Sevcík, and then became one of many leading Polish violinists to go through the hands of Mieczyslaw Michalowicz, a pupil of Barcewicz and Auer, in Warsaw. Aged eight, he went to Berlin and soon became a pupil of Carl Flesch, the most analytical pedagogue of that era and, like Auer, a Hungarian. Flesch had studied in Vienna and Paris and thus combined the best of central European and Franco-Belgian influences; but in style, repertoire and taste he often seemed quite German. Under his tutelage, Goldberg played such archetypal virtuoso concertos as the Paganini D major and Joachim ‘Hungarian’, but quickly graduated to be concertmaster of German orchestras, first the Dresden Philharmonic and then the Berlin Philharmonic, where he also led a quartet composed of BPO members and, outside the orchestra, participated in a famous string trio with Paul Hindemith and Emanuel Feuermann. Had it not been for the human and cultural catastrophe of the Third Reich, he might well have remained in the Austro-German sphere of influence.

As it was, Goldberg was forced into a wandering existence, at first in a still unforgotten duo with the Hungarian pianist Lili Kraus – their tours took them so far afield that during the war they became prisoners of the Japanese. After the war, Goldberg continued his wanderings for a decade and actually became a United States citizen in 1953, before finding an ideal base in Amsterdam, as director of the new Netherlands Chamber Orchestra: he stayed for 22 years, giving myriad concerts and making many recordings as both soloist and conductor. The basis of the orchestra’s repertoire was the Baroque and Classical music of Vivaldi, Bach, Handel, Haydn, Mozart and Schubert, but Goldberg made sure he included works by his old friend Hindemith and other contemporary composers such as Bartók, Milhaud, Stravinsky, Badings, Schoenberg, Honegger and Skalkottas. He found time to pursue his international career, especially in America, where his summer teaching work at the Aspen Festival led to the famous piano quartet ensemble known as the Festival Quartet, with Victor Babin, William Primrose and Nikolai Graudan. With Joanna and Nikolai Graudan he also had a wonderful piano trio ensemble.

From 1969 Szymon Goldberg was based in London, where he taught and had a duo with Radu Lupu, while keeping his Amsterdam post. For two years he conducted the Manchester Camerata. In 1978 he moved to the United States, teaching at Yale University, the Juilliard School, the Curtis Institute and the Manhattan School. In 1987 he moved to Japan and from 1990 he conducted the New Japan Philharmonic in Tokyo, also becoming a visiting professor at the Toho Gakuen School – after the death of his first wife he had married the Japanese pianist Miyoko Yamane. It was typical of him to forgive the people who had held him captive during the war. He died in Toyama on 19 July 1993, aged 84.

Everywhere he went, Goldberg propagated the teaching methods of his mentor Carl Flesch, but without the intense pressure which always attended Flesch’s classes – and which some students did not survive. Goldberg was above all a humane man, softly spoken and with a good sense of humour: his teaching was directed towards achieving the same divine simplicity that his own playing evinced. For him, the best art was the art that concealed art. His rhythm arose naturally from the essence of the music and did not need to be applied from the outside. His phrasing was based on the principles of singing – it had a breath. He left recordings with all of his ensembles, as well as various concertos and other solo pieces, so his influence continues even though the man himself has left us.

Photo: Evelyn Hofer

Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial. To purchase back issues click here.

No comments yet