Composer Nimrod Borenstein, who has written a new violin concerto for Dmitry Sitkovestky, writes about historical precedent, expectation and the challenge of beauty

A couple of years ago, in a moment of inspiration, I decided

that I would spend the next decade or so writing concertos for all

sort of instruments. As a violinist myself it is not surprising

that I started this project with concertos for string instruments;

a cello concerto (premiered in July 2013) was followed a year later

by a violin concerto for Dmitry Sitkovetsky, which will be

premiered this month.

The concerto is a form that fascinates and inspires me. Feeling

that the creation of contrasts is one of the central tenets of

music and arts in general, I love the endless possibilities the

concerto offers in contrasting the full orchestra against the

soloist. For me the soloist is a metaphor of the human being and I

tend to develop the soloist’s line as theatrical monologues and

dialogues with the orchestra in which the main character reveals

his most intimate feelings and thoughts.

Since I started composing as a young child it has always been my

main desire to write music that would stand proudly next to my

gods, which at that time were Beethoven and Bach. Since most

composers of the past have written concertos, the form is an ideal

candidate to allow one to confront the great music of the past and

the burden of history. Even before starting writing a single note

of music I felt the weight and fear of the task. But are not

challenges the spice and excitement in life?

After choosing the desired size of the orchestra, my first choice

was deciding on the length of the work. Was I going to follow the

line of ‘short’ violin concertos (Bach, Mozart, Mendelssohn,

Prokofiev) or the one of ‘big’ concertos like Brahms, Sibelius,

Elgar or Shostakovich? Having just finished a ‘short’ cello

concerto – and very eager to make a mark on a subject so close to

my heart – I decided on the ‘big’ model.

The second question, still a formal one, was the number of

movements I would write – three or four? After writing my first

movement which was essentially fast-paced, I wrote a second

movement that was romance-like. Though, whilst it was lighter and

slower than the first movement, it was not a slow movement. Since I

am always mindful of the necessity of contrasts in music, and I

wanted to end the concerto with a fast fiery movement, I therefore

needed the third movement to be very slow to allow for maximum

contrasts. This therefore had to be a four-movement concerto.

I did not listen to other violin concertos before starting to write

my own; after all, I know most of them by memory, having loved them

all my life. The concerto is very much a gladiatorial experience

for the soloist but one should not forget that it is also an

experience of tremendous importance for the composer. The soloist

has to fence with the many artistic and technical difficulties but

so does the composer in facing the glorious ghosts of the

past.

Central to my composing a violin concerto in the 21st century, was

the concept of virtuosity – so essential to this form. I conceive

virtuosity as not only the capacity to play fast and precisely, but

even more essentially as the mastery of colours and nuances and the

individuality of the voice. I have searched, and hopefully found,

many new ways of writing for the violin including new

double-stopping techniques, unusual combinations of notes as well

as a complexity of rhythm. In all this search for novelty and

renewal in virtuosic writing, it was always important for me to

give the best light to the unbelievable beauty of the violin

sound.

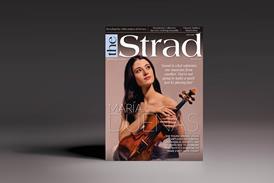

Nimrod Borenstein’s violin concerto will be premiered by Dmitry

Sitkovestky and the Oxford Philomusica, conducted

by Marios Papadopoulos on Saturday 17 May 2014.

Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial. To purchase single issues click here.

No comments yet