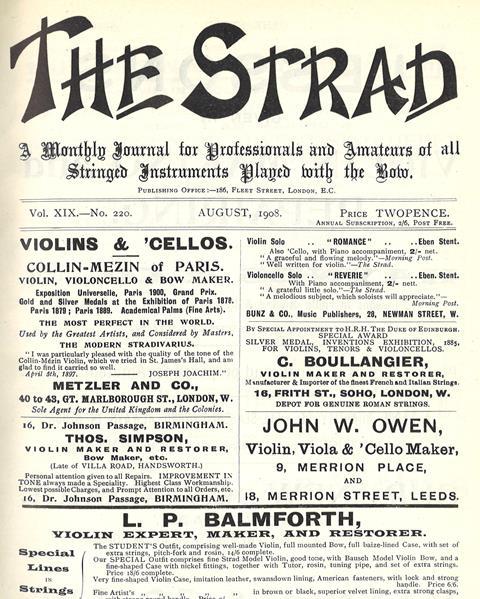

Holidays are a vital part of learning, according to an article from The Strad, August 1908

On Holidays by L. H. W.

'Dear me!' says the conscientious student, 'what can this, possibly, have to say to the violin?'

Well, my friends, it has considerably more to say to it than you imagine. Indeed, sitting as I am this moment in the heart of clover field, listening to the bees humming happily at the honey bags and the larks weaving spirals of song between heaven and earth. I know that I should be doing a great deal more good than preaching if I could only load a few hundred industrious students on a magic carpet and transport them into the midst of it; or scatter them, let us say, a few fields off: for it is the solitude and the murmurous stillness that is so healing and so wholesome.

But they must dust their minds clear of musical cobwebs and let the sweet wind have free play in the musty corners. For it is little or no good to give the fingers rest unless the brain has rest also. Besides, knowledge ripens in silence. You may practise a study or a solo daily, hourly, a thousand times, with no result save innate weariness and discouragement; but put it by for a while, and the understanding of it will grow slowly, imperceptibly within you, until, on returning to the struggle, the fingers do, of themselves, what you strove in vain to effect in time past.

Some intelligences move more slowly than others, and it is useless to hurry them beyond their capacity. Nature will not haste for all your hectoring. But come to her humbly and trustingly, and she has ways of teaching that are infinitely more sure and satisfying than are the elaborated systems of men. Nature seldom or never specialises. All her arts, crafts, and sciences are allied, interpenetrable. She plucks you blossoms of joy from off the tree of pain, and teaches you by means of sternest life to play more whole-heartedly. And as the fields will not beat food yield of the same crop in successive years, so the human brain will yield sparse fruit and poor if it is sown too often with the same thoughts and ploughed in the same furrow. Change, freshness, wide culture; all these are necessary to the violinist who would be more than a mere drudge.

For music is not a branch of manual labour: it is the rhythmical language of the universe; the voice of things dumb, the soul of things unseen. He who trudges in a perpetual round of scales, studies and prescribed solos, how can he put any fresh life into his music? He has no influx of outward and varied experience. His road is narrow and straight, and runs between high walls. But let him only open a door and go out upon the hillside. Let him forget for a space that he is:– that Rode ever wrote caprices or Wessely compiled scales;– let him stand, agaze and glad, as a little child in a field of flowers. And when he turns again to the narrow road there will be new clearness in the old notes, a sweeter lily in the well-worn phrases.

In cases where direct recourse to nature for rest and inspiration is difficult of attainment, an alternative study of different character, or even a purely recreative hobby, is of importance to the student, as affording the necessary mental variety. I cannot sufficiently impress upon enthusiastic students that the study of music, alone, will never make them great musicians. (I purposely reject the word artist as it has frequently of late been associated with performances of solely technical interest.)

It is the keenness of competition, not for a competency, but for affluence, which gives rise to so much over-practising, wrecked health, and stunted individuality. What is the value of ephemeral wealth and popularity if the possessor is, humanly speaking, a loser thereby? Undoubtedly, the gilded laurels are very tempting to the majority of violinists; but high tides ebb quickly, and the performer who depends upon tours de force for his success is liable at any moment to be passed in the race. To 'hasten slowly,' as the wise Latin proverb has it, is indisputably the better course, and the bringing of all the gifts and capacities to natural maturity is eventually productive of a much finer creature than the forcing of a particular talent to abnormal luxuriance. Unfortunately, the tendency of the age, and of its economic conditions is to grudge the time necessary for all-round development; but somewhat in the right direction may be done by students for themselves, if they only grasp the central idea;– that a minimum of rest and variety is absolutely essential to growth.

There are some violin students who, on reading this apotheosis of rest and variety, will feel it in instinctive harmony with their private desires and sentiments. They will receive it as a heaven-sent message, and put it into immediate practice. But it is not meant for them. No, it is net to the student who does not desire it; who, indeed, repudiates it angrily; wishing, only, to go on practising as long as those poor slaves, his fingers, can be spurred into action by a masterful will. And when his body is tired out, and he must, perforce, cease playing, his mind has not the vitality to project itself into a fresh atmosphere, but jogs along, by tones and semitones even in his sleep.

Yet, in the busiest cities there are green and quiet corners for

those who would sit awhile apart; there is the refuge of books,

written in many tongues and reflecting many personalities; there

are worlds of colour, of human intercourse, of philosophy and

speculation; all these await only the opening of the door in the

narrow way, that way that grows ever more narrow, more dusty, as

the days pass by.

Subscribe to our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial.

No comments yet