In this article from The Strad, February 2011, Peter Somerford looks into the murky world of international Stradivarius violin theft, and the efforts being made towards recovery and prevention

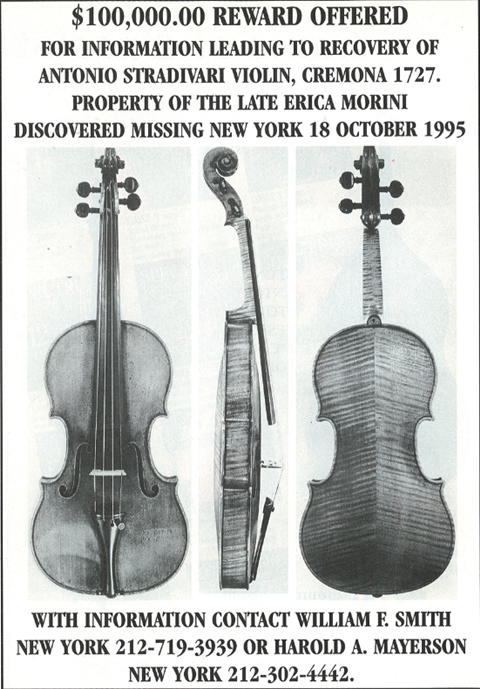

Losing a Stradivarius must rank high among a violin virtuoso’s worst nightmares. As Korean violinist Min-Jin Kym found out recently when her Stradivarius was snatched as she grabbed a sandwich at London’s Euston Station, it only takes a few moments of inattention or distraction for a million-pound instrument to be spirited away by an opportunist thief. She isn’t the first to have a fine violin stolen this way, and she won’t be the last. More than a dozen Stradivarius violins have been reported stolen in the past 30 years. Most were taken in break-ins or burglaries, but a few went missing after being left momentarily unattended or unwatched. Because such instruments are virtually impossible to resell on the open market, one might think that the chances of recovering them would be high. But several of the most notable Stradivarius violins stolen in the last 30 years – among them the ‘Colossus’ and the ‘Davidoff’, ‘Morini’ – remain missing, and the time taken to recover others has varied from just a few days to two decades.

The job of finding a stolen Stradivarius is rarely left to the police alone. Insurance companies, networks of auction houses and dealers, national and international databases of stolen instruments, specialist recovery services, even private investigators and kidnap negotiators can all become involved. Few countries have a division of police detectives at hand who are dedicated to solving art and antique crime. In the UK, for example, there are four investigators in the Metropolitan Police’s art and antiques unit, while the FBI’s art crime division has just 13 agents covering the whole of the US. Only in Italy, where more than 300 officers work in the Carabinieri Division for the Protection of Cultural Heritage, does the theft of art and antiques seem to receive serious attention and resources. Richard Ellis, who set up the Metropolitan Police’s art and antiques squad in 1989 and now works in the field of art protection and recovery for the Art Management Group, says: ‘The police resources applied to serious property crime have been reduced in the last decade. Insurers may circulate information on stolen instruments, but there are very few people actively involved in investigating thefts of art and antiques. Private sector databases have recovered more stolen items from the market than the police have on their own, so they provide an important function.’

The art loss register (ALR) is one such international database. It works with police forces and insurers to register and search for stolen items, and allows owners to give ‘positive’ registrations of their instruments while they are still in their possession. Buyers also use the database as a due diligence measure when weighing up potential purchases. ALR executive director Christopher Marinello, like Ellis, bemoans the lack of government resources given to art crime: ‘We need to put some priority on these types of crimes and realise that they’re culturally more significant than they’re currently given credit for. As more funds are being directed to drugs and international terrorism, art crime is one of the areas that suffers.’

Marinello says that since the ALR was set up in 1991, the job of searching for stolen instruments has been made easier by the internet and online auction catalogues, and lately image recognition technology. He also notes that art crime and instrument crime have become more and more similar. ‘With all the publicity every time a Stradivarius or Guarneri “del Gesù” breaks an auction record, people take notice. The thieves read the trade papers: they know what the prices are like. And they know it’s easy to walk off with a fine instrument. The higher its value, the more difficult it is to offload, but thieves don’t always think about that at the time, which is why we find a lot of fine instruments travelling in the underworld at a reduced value.’

One player who had to prise his Stradivarius from the criminal underworld was French violinist Pierre Amoyal. In 1987 he was about to leave a hotel in Saluzzo, Italy, when a small-time gangster stole his Porsche and sped off with the 1717 ‘Kochanski’ inside. It was four years before the violin was recovered, the instrument having passed between thieves and into the hands of an antiques dealer who was known to the police. Eventually a judge allowed a mafioso to be taken out of jail temporarily to set up an exchange with the dealer. The sting operation ended – as with the recovery of the ‘Sinsheimer’ Stradivarus in Germany two years ago (see The Strad, November 2009) – with the police storming in and arresting everyone.

Reflecting on his experience, Amoyal says: ‘I was fortunate that, for the police in Italy, such an important instrument represented something special. They did the best they could, but it was not enough and I had to hire private detectives and a lawyer who had experience of dealing with the mafia and kidnap cases. However, at the end, the police did a very good job – they were very careful. I told the prosecutor that I would prefer never to see the violin again rather than it be destroyed by criminals knowing they were about to be caught.’

Stolen Stradivarius instruments that do surface months or even years after their theft are occasionally offered to dealers or directly to musicians. For example, violinist Erich Gruenberg was reunited with his Stradivarius, stolen from a luggage cart at Los Angeles International Airport in 1990, when a player in Honduras was offered it for sale nine months later and tipped off the police. But Geoffrey Fushi, of Chicago dealers Bein & Fushi, says approaches from people offering suspected stolen instruments are exceptionally rare and immediately raise suspicions: ‘We have had one or two come in over the years, and we could tell very quickly that there wasn’t any reason for those individuals to have the instrument legitimately, so we called the police.’

One stolen Stradivarius that almost made it through to be resold on the open market was a 1727 violin owned by the Dallas Symphony Orchestra (DSO) and stolen in 1985 from the orchestra’s then-concertmaster Emanuel Borok when the DSO was on tour in Europe. Twenty years later a retired DSO violinist spotted it in an advertisement in The Strad for an upcoming auction at Bonhams, and after a period of negotiation the orchestra was eventually able to reclaim it. The incident is perhaps a reminder of the importance of due diligence and provenance investigation for any dealer or auction house. Bonhams’ head of musical instruments, Philip Scott, reflects: ‘Over time, I’ve sadly become a little more suspicious than trusting. My instincts are well developed and if I’m in any doubt about an instrument I leave it out. But this is still the age of discovery and people do still find extraordinary instruments, so you have to allow for that. It might therefore appear that you’re being offered something remarkable by someone you wouldn’t necessarily expect was the owner of it.’

With the chances of a stolen Stradivarius re-emerging being so rare, Scott says the big lesson is that musicians should be extra careful when they’re in charge of other people’s property. Fortunately for the string world, the regular stories of relatively young soloists losing their loaned old Italian violins don’t seem to discourage the trusts and foundations doing the lending. Bein & Fushi’s Stradivarius Society has a contract with the recipients of its instruments which includes a general instruction to have personal touch with the instrument at all times, as well as specific cautions against leaving a violin unattended in a hotel or vehicle. But the idea of insisting that a musician should never stray more than a few feet away from their loaned instrument does not appeal to Nigel Brown, found

No comments yet