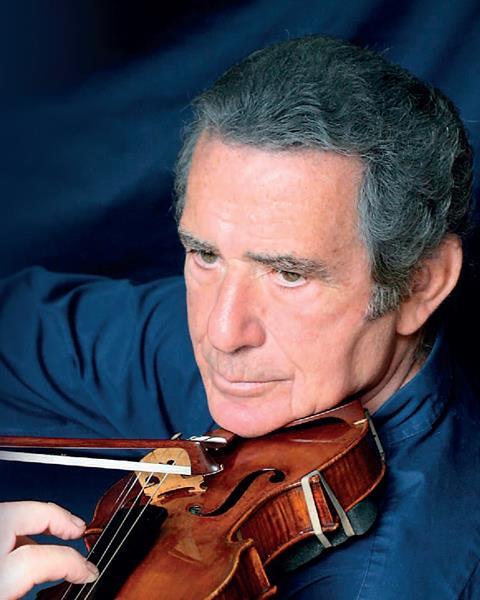

The former concertmaster of the London Philharmonic, New York Philharmonic and BBC Symphony shares his experiences with conductors - great and not so great

As an orchestral leader your first priority at all times is to support your orchestral colleagues and I have found the best way of doing this is to establish a comfortable rapport with whoever is on the podium. If you can achieve this – professionally and socially as well – everything else just falls into place. In the case of Bernard Haitink, for example, he would often come to my dressing room before a concert and we would chat about all kinds of things (he loves a good joke), because we had such a fine working relationship and chemistry.

If there is one thing the truly great conductors have in common, whatever their public image, it is their essential kindness and respect for players. A conductor, beyond being a great musician, must value honesty. No matter how expertly he may wave his hands around, it is all to no avail if he is ultimately more concerned about image than the music. You know when a conductor is the real thing because the whole orchestra experiences a collective buzz like an electric current surging through it, and it brings your playing up to a whole new level. It’s the difference between a concert you forget the minute it’s over and one that sticks in your mind so firmly that you can’t eat or sleep afterwards.

Inevitably there are some conductors you have to carry, but the word quickly goes around to ignore them. I remember one, who shall remain nameless, conducting The Rite of Spring with the New York Philharmonic, and every time he left the podium to hear how it sounded in the auditorium, the playing immediately improved! A great orchestra of highly trained musicians needs only musical inspiration.

Bowings are an essential issue for string sections, although conductors vary enormously in terms of how far they want to get involved. Solti, Bernstein and Boulez tended to leave me to sort things out, for example, but Barenboim was keener. So was Giulini who, incidentally, was the most gentle and self-effacing of all the ‘greats’. On one occasion, Giulini decided – having been up half the night worrying about it – to take my advice on a particular bowing in Beethoven’s Seventh Symphony. He came in early the next morning and personally changed every string part before the orchestra arrived for final rehearsals.

Perhaps the highlight of my orchestral career was the legendary 1978 concert in Carnegie Hall with Eugene Ormandy, the New York Philharmonic and Vladimir Horowitz as soloist in Rachmaninoff’s Third Piano Concerto. I shall never forget the first rehearsal. Horowitz came in and we immediately sensed this extraordinary presence. He sat down, we played the concerto’s opening couple of bars, he started to play and I remember thinking I had never heard anything like it. I felt like a child again, sitting in wonder at what I was experiencing. After the rehearsal, Martha Argerich came up to me and humbly despaired: ‘You know what – we don’t know anything!’ It was musical history in the making.

Read: Are conservatoires preparing young string players for the music world, asks Rodney Friend

This article was first published as part of a larger feature in The Strad's February 2012 issue - download on desktop computer or through The Strad App.

No comments yet