The ninth Great Wall International Music Academy, which took place in Beijing in July, forged connections both musical and social between young musicians from east and west that will enrich their careers, says Nancy Pellegrini

When two consummate educators share the same vision, everyone wins. And when Cincinnati College–Conservatory of Music professor Kurt Sassmannshaus and the late, great Chinese violin pedagogue Lin Yao Ji created the Great Wall International Music Academy (GWIMA) nine years ago, China could offer the same, concentrated musical experience that Americans and Europeans take for granted. Over the years, GWIMA has honed its chamber music focus, seen its former members return as faculty, watched talent levels continue to rise, and this year, even added a piano department.

The academy is located in a leafy, self-contained community on the outskirts of Beijing, and its 60-odd students follow a heavy regimen of private instruction, masterclasses and chamber music training – but they still have enough time to hit the restaurants, play badminton, and take field trips into the city. ‘At other festivals, the students only have time to practise, eat and sleep, but here the kids can see Beijing and eat a lot of Chinese food,’ says viola professor Wang Shaowu. ‘And the Chinese kids can practise their English and learn communication skills,’ he continues. ‘They really help each other.’

This resonates particularly in chamber music, a GWIMA pillar that Chinese conservatoires until recently considered a waste of time. ‘Kurt has been adamant that chamber music should be an equal part of the syllabus here,’ says Daniel Avshalomov of American String Quartet (ASQ), which joins the Great Wall Quartet (GWQ) as regular GWIMA instructors. ‘Kids are initially drawn by flying around the instrument playing Paganini and Sarasate, but they’ve come to see there are different challenges to playing a phrase of Mozart, too.’ Violin teacher Nancy Tsung points out that students who limit themselves to solitary practice can not only feel lonely but also have unrealistic aims. ‘If I play with someone else, they can reflect to me what I’m doing, and when we discuss it, we come up with something even better,’ she says. ‘Chamber music not only trains my ear, but also lifts me to another level.’ Better still, quartets and trios are windows into compositional history. ‘You can get a lot closer to a composer by doing chamber music,’ Sassmannshaus says. ‘Musicians see a score both horizontally and vertically. It’s essential to artists’ education.’

The debut of GWIMA’s piano department not only made the jobs of the staff’s collaborative pianists easier, but also introduced piano trios, an ensemble that Avshalomov feels is ideal for chamber newbies. ‘The intonation is dictated by the piano, but besides that, you have fewer voices to keep track of,’ he says. ‘Sometimes the violin melody is doubled in the right hand of the piano, and maybe the bass-line is doubled in the cello. You have a lot of support.’

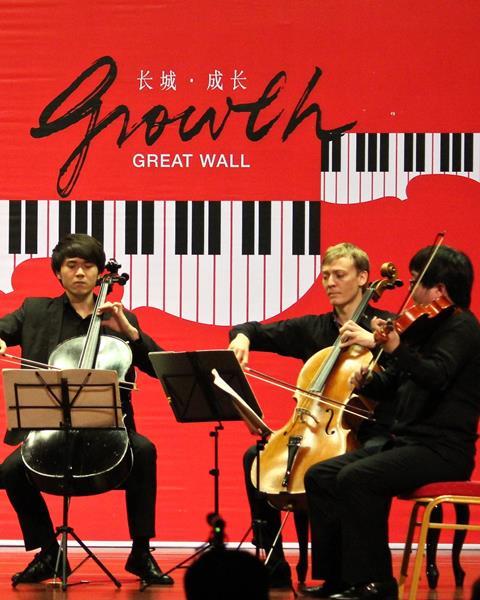

Shortly after the GWIMA winter auditions, Sassmannshaus assigns chamber ensembles and pieces according to skill level and basic ages. Groups then work at the academy with members of both the ASQ and GWQ, and participate in a low-pressure competition. At times, the levels of musical understanding and cohesion are staggering – there were several quartets at this year’s event that you hoped would stay together. Even younger trios showed promise – Zheng Shuidie, Zhang Zongheng and Lv Xinyang took third prize with Beethoven’s Piano Trio op.1 no.1. The ASQ judges felt that ‘they had a nice sense of style and worked hard’.

Other prizes went to the older, more advanced quartets. Zhang Ying, Li Quanshuai, Lv Anqi and Fang Yijia took second prize with the Brahms A minor Quartet. ‘They rehearsed all the time,’ says Avshalomov, their camp instructor. ‘They were very serious, they cared a lot, and they asked penetrating questions.’ As for winners Tan Yabing, Liu Yang, Mei Diyang, Christoph Sassmannshaus and Zhang Hong, who played the Schubert Quintet, Avshalomov calls them the ‘all-star group’. ‘They’ve been here for several summers, and they had one of the greatest pieces in the repertoire,’ he continues. ‘Small wonder they went the distance.’

Of course, the ASQ set a great example, providing the musical equivalent of ‘having it all’ – a residency at New York’s Manhattan School of Music, a vibrant concert schedule and a fantastic breadth of repertoire. The group’s concert programme of Haydn, Shostakovich and Dvorák illustrated the quartet’s vast universe of chamber repertoire. Even better, the players showed aspiring chamber musicians that groups that have performed together for over three decades can not only achieve telepathic communication but can also retain freshness and excitement. The Sassmannshaus Piano Trio also gave a stunning performance, where violinist Kurt and cellist Christoph showed the visceral connection that most fathers and sons desire but rarely experience. ‘I know I’m going to have the melody with the first violin, and I look over and it’s my dad,’ says Christoph, himself a natural chamber player. ‘There’s another layer of enjoyment on top of our already awesome relationship.’

But GWIMA students don’t neglect their solo training. The concerto competition showed strong talent, with the technical level highest in the violinists, followed by the cellists. Both sets of instrumentalists prepared a single movement of a pre-approved concerto, and judges tested the violinists piecemeal over an entire work. ‘Otherwise the whole camp would apply,’ says Sassmannshaus. ‘This makes it a little more challenging.’ Although students were more comfortable with forte passages and rapid fingering, quite a few showed dynamic sensitivity and clean, pure tones. In both competitions, winners received cash, GWIMA scholarships and BAM cases, as well as performance opportunities. This year’s winners (in descending order) were violists Lv Anqi, Chen Xi and An Du, cellists Zhang Hong, Fang Yijia and Ben Fryxell, and violinists Tan Yabing, Zhang Ying and Li Quanshuai. Take note – you’ll no doubt see these names again.

But beyond concerts and classes, GWIMA is about connections. ‘It’s a good atmosphere and a close environment here,’ says violin teacher Kun Hu. ‘Students are very positive, they work hard and they ask questions.’ Christoph Sassmannshaus agrees: ‘The Chinese and Western kids get really close. We sit at the same tables and hang out in each others’ rooms.’ This, Kurt says, is crucial. ‘Seeing Chinese students teach Australian kids how to bargain for a T-shirt or a remote-controlled helicopter is both amusing and important,’ says Sassmannshaus. ‘They are the future top of the profession and will meet each other again. They don’t realise it now, but the trust created by eating together, performing quartets together and playing video games together is golden when it comes to professional trust and opportunities down the road.’ And having fun can’t hurt either.

Subscribe to The Strad or download our digital edition as part of a 30-day free trial.

No comments yet