The Louisville Orchestra's management is advertising for musicians – but it's the players themselves who really need a hand, argues Heather Kurzbauer

The Louisville Orchestra’s management is advertising for musicians – but it’s the players themselves who really need a hand, argues Heather Kurzbauer

At the end of last year, the much-touted documentary Music Makes a City made its British debut on DVD. The 2010 film tells the story of how an impoverished US city, battered by post-Depression industrial malaise and environmental disaster in the 1930s, recreated itself through decades of music making. The location: Louisville, Kentucky. The orchestra: the Louisville Orchestra. Fast forward to Louisville in 2011, where unemployment and economic woes plague the city, and the orchestra finds itself an endangered species.

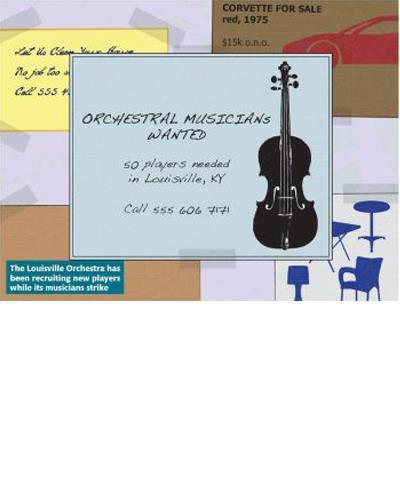

In November, aficionados of the Craigslist online network were surprised by a job listing. Music job offers on the site are more likely to propose wedding gigs or lounge dates. The listing, in part, read: ‘Openings are available for qualified symphonic musicians looking for permanent employment to replace musicians who are on strike. All orchestral positions presently available.’ Louisville has descended from troubled to unconscionable.

Since the orchestra filed for bankruptcy reorganisation in 2010, musicians and management have been jousting over several key issues including the size of the orchestra, the total number of performance weeks and a controversial clause in management’s proposed contract that would prohibit musicians from performing in other area venues. Adding insult to injury, the Louisville Orchestra has contested its musicians’ claims for unemployment benefits, arguing that striking musicians should not be eligible for any sort of payment. Louisville Orchestra musicians have had no contract since May 2011. No contract, no benefits.

Most recently, Louisville’s orchestral players have been presented with a point-blank ultimatum: accept the offer or management will hire permanent replacements.

String players are leading the charge for the musicians’ rights. Violinist Kim Tichenor is heading the negotiating committee in Louisville, while bassist Bruce Ridge, chair of the International Conference of Symphony and Opera Musicians, penned a passionate response to the Craigslist advertisement. ‘Any musician accepting such work would not be serving the cause of art in America, or serving their career and family,’ he wrote. ‘Musicians accepting work as replacements would be taking food out of the mouths of fellow musicians, as well as depriving them and their children of health insurance.’

Seismic shifts in cultural spending and problematic dealings with board and management might account for a hefty portion of Louisville’s demise. However, no amount of financial distress should lead to the management seeking new musicians, ostensibly to rebuild an orchestra, while its players are on strike.

The problems in Louisville can be seen as part of the general downward spiral affecting cultural institutions worldwide. Within the last few years, persistent deficits and a shrinking demand in the face of rising ticket prices have forced many a well-respected American orchestra to close its doors forever. Recession and shrinking budgets are but one part of a complex story: most failed symphonies share a storyline that centres on ineffectual management, thorny relationships with board members insensitive to musicians’ demands, the increasing costs of soloists and conductors, and changing community demographics and expectations. Nowadays, management and board members are apt to be at loggerheads with musicians and their unions.

At the end of November, the German parliament voted to add a cultural stimulus package to aid and abet institutions in need of assistance. Across the pond in the US, the Detroit Symphony is back at work under a new contract that runs to 2014. At the same time, back in Louisville, the Kentucky Opera’s production of The Marriage of Figaro has had to open with an orchestra pit standing empty, save for two pianists and a harpsichord player. The silence in Louisville has become deafening.

No comments yet