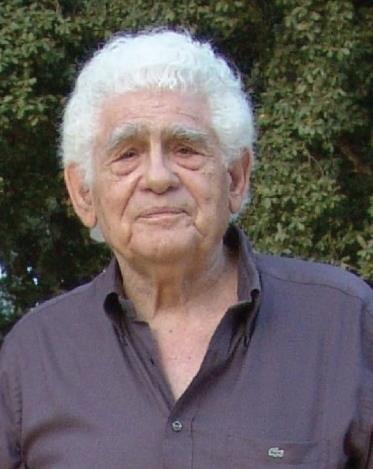

The former Israel Philharmonic Orchestra concertmaster shares his thoughts on working with good and bad conductors, and learning to listen to listen

On listening to other sectionsWilliam Steinberg was the principal conductor when I was a first violinist with the Pittsburgh Symphony Orchestra. He was good, but had a strange method of conducting – he always used to beat before the orchestra. We were practising Brahms’s Third Symphony at my first rehearsal and I found I had no idea what to do. This was my first professional job with a big orchestra, and I felt it was terrible, so I started listening to the other sections. That’s how I really learnt how to be an orchestral musician, as the most important thing is to play in relation to the others. Playing chamber music is good practice for listening – if you’re in company, you’ve got to be together. When I was a student, my ambition was to be a chamber musician, not a soloist. But nowadays, there are so many young players that want to be soloists – orchestras are seen as a kind of last resort.

On working with bad conductors

I remember concerts that felt like they weren’t going anywhere – nothing moved at all. So I’d give a certain look to the principal cellist, violist and second violinist to say, ‘Follow me’ – and suddenly the orchestra would become quite good. Then the conductor would be very happy as he thought he’d done it. Sometimes the conductor’s beat was so terrible that I had to put my eyes down, otherwise he’d have had to stop because of me. In my opinion, conducting is both the easiest and the most difficult profession. So many conductors will come on stage, cut the air with their hands and jump around, and audiences are delighted, even though musically there’s nothing. At the Israel Philharmonic we had so many top guest conductors who turned out to be just like that. It’s like the emperor’s new clothes. It’s up to the concertmaster to know what the conductor wants, though. If one has that understanding, then the section will have confidence in the conductor. So I used to talk to the conductor a lot. We also had conductors who would simply stop conducting if a player made a mistake in a concert – their hands would keep on moving but that’s all. Many conductors are like little kids: if they don’t get what they want, they’ll start to sulk and kick with their legs. So it’s very important that the concertmaster knows exactly how to talk to them.

On working with violinist-conductors

It’s certainly good for the string section if a conductor can give good advice on bowings, fingerings and how to play a piece. When conductors suggest fingerings, I listen to what they have to say and then make my own suggestions. And most of the time, mine are accepted. Some conductors will arrive with a score in which the bowings are already marked. If they already know what they want, I don’t argue. Others might call from abroad to say, ‘Please put these bowings in before I come.’ I don’t do that. When they ask me why not, I say, ‘Because I don’t know how you’ll conduct it – fast or slow – and the bowing depends on that.’ At the first rehearsal I find out how they’re going to take it, and then I write in the bowings.

On correcting mistakes in the violin section

If I could hear that something wasn’t working for a section player, I didn’t want to get up and tell them they weren’t playing it right. Instead, I would have a good friend at the back of the section, and I used to get up and talk to him. Then the things I was saying would be heard by the whole section. I never made myself out to be important. They were all good musicians and I respected every one of them

Interview by Christian Lloyd

Photo: Courtesy Keshet Eilon Music Centre

This article was first published as part of a larger feature in The Strad's October 2012 issue - download through The Strad App

No comments yet