The life of the US musician, born 125 years ago this month, is celebrated in our August issue. Here's an interview with Spalding at the start of his career

At the height of his career, Albert Spalding was known – and indeed publicised – as ‘The Greatest American Violinist’. Born on 15 August 1888 – 125 years ago – he eschewed virtuoso histrionics in favour of a refined musical sensibility – an approach that brought him an international touring schedule, a vast number of recordings and regular broadcasts on American radio. A hero of both world wars, he was called ‘not only a wonderful violinist, he is also a distinguished citizen and patriot’ by his friend and colleague Fritz Kreisler. In our August issue, Dario Sarlo pays tribute to Spalding and assesses his legacy to the string music world.

In January 1907, The Strad published an interview with Spalding, then just 17 years of age. Already he had gained a reputation in Europe, having played ‘in the principal towns of Austria, Germany, Italy, and France’. Here, Spalding discusses his playing style, his choice of instrument and his encounters with Saint-Saëns and Joachim:

Albert Spalding, though born in America, is of English descent. From a child he has shewn a remarkable love for music, and was presented at his own request with a tiny violin when he was seven years old. He soon shewed so much promise that he was placed under the care ofd Ugo Chiti, in Florence, where his parents reside in the winter, and during the summer months, in America, he studied with Juan Buitrago. Ugo Chiti was so much impressed by his pupil’s talent that he suggested entering him for the severe examination necessary to qualify for a professorship at the Bologna Conservatory of Music. The boy, then fourteen years of age, passed with flying colours, gaining forty-eight marks out of a possible fifty, to the amazement of a board of professors. These latter declared him to be the youngest professor ever nominated, but, on searching the books it was discovered that Mozart had passed the same examination for the pianoforte just 133 years before. Two years in Paris, under Lefort, finished his period of study, and in Paris, he made his début at the Nouveau Théâtre. Since then he has played in the principal towns of Austria, Germany, Italy, and France, and finally made his first appearance in England last Spring, with what results most lovers of the violin are well acquainted.

My interview with him took place in the artist’s room at the Queen’s Hall after a rehearsal, on a damp, dripping day, such as only London can produce. “I admire your courage in rising to the occasion so valiantly,” I remark as we shake hands.

“Oh, I don’t mind the weather, and I always enjoy playing with the orchestra so much that I don’t notice anything.” This appears to be a fact, for Mr. Spalding looks as fresh as the traditional paint, while everyone else seems shivering and uncomfortable.

“Tell me a little about yourself,” I say as we settle down for a chat. “Well, I don’t know what to tell you that is of any interest to the public.” “Is that your celebrated Montagnana violin,” I ask, as he carefully puts away the instrument from which he has just been drawing such clear silvery tones.

“Yes, that is the violin that was given to me by my grandmother on my first appearance in Paris the year before last. I could have had my choice of two Strads at a higher price, but I don’t consider either of them equalled to this one in tone. It was very funny when I played in Bristol last week to hear the remarks passed on it. A rumour had gone round that it was a very expensive instrument, and one lady was heard to remark that the violin I was playing on cost £10,000!”

“Are you nervous when playing in public?” “No, I cannot say that I am. I am naturally a little excited before playing, but once on the platform I enjoy it. The only time I ever remember feeling nervous was when I was to play with Saint-Saëns at the Pergola theatre in Florence. I had heard that he was sometimes a little abrupt with musicians that did not please him, and as I was to play his compositions I was naturally a little anxious. However, I found him perfectly charming and most kind.”

Mr. Spalding does not add that the great French composer expressed himself delighted at the violinist’s interpretation of his great concerto, but this is a fact which I learned from other sources.”Do you practice a great deal?”: “No—that is to say I have never over-practised. Many average is about three hours daily, but I always make it a point never to let a day pass without working if I can help it. In travelling about it is sometimes difficult to arrange, but at home I do a great deal of work, also at harmony and composition.”

“Have you any idea of conducting?” “No, that is not my ambition, but I should love to compose, and mean to devote a certain part of my study time to that.”

“You are doing a very generous work in helping to make known the compositions of the British school in your recitals.”

“Oh, I don’t know about that. I thoroughly enjoy meeting the composers, and I am only too glad to get a hearing for new works, as I believe many valuable works are lost through lack of an opportunity to bring them before the public.”

“Have you any other hobbies besides music?” “Yes, I am passionately fond of sport, but there are certain forms in which I dare not indulge, as I like to keep my hands supple.”

“What is your favourite school of music?” “All music that is good appeals to me, but, if I have any preference, it is for the German classical school. Bach and Beethoven are my ideals in music, which, I suppose, is the reason for my great admiration for Joachim.”

“Have you ever met him?” “Yes, I spent some time with him at his home in Berlin and played for him, and I shall not easily forget his kindness and encouragement.”

“How do you like England?” “Oh, immensely. I think it is a grand country, and I love the English audiences, they are so enthusiastic.” “You do not find us cold and unmusical then?” “No, indeed, far from it, I am struck with the way you appreciate what is best in music.”

There is much more of interest to discuss but time forbids, and I can only give my readers a short sketch of a very interesting personality.

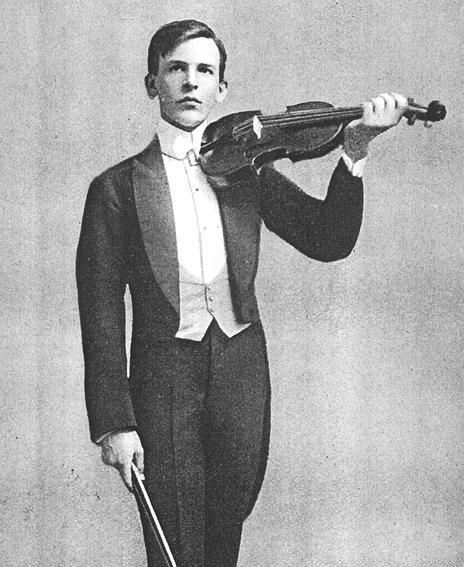

Tall, slight and well-built, Mr. Spalding gives the impression of being older than his seventeen years until one is near him, and then the indefinable look of youth and its freshness strikes one, as do also the latent possibilities of strength and power in his face. The youthful artist owes much of his success to his mother, who is herself a cultivated musician and highly intellectual woman, and has watched over her son’s career, step by step, with a care and judgment strongly averse to the forcing system for prodigies. Mr. Spalding does not pose as a prodigy but as an artist, and essentially a healthy artist. His common-sense teaches him that he is not yet at the apex of his powers, and that every year devoted to his art will develop fresh mental powers. About his playing so much has been said that it suffices to mention his tone, silvery and of penetrating pure quality, his facile technique, and above all an unaffected style, free from mannerism and claptrap, which serves better than anything to point out his earnestness of purpose. In five years, probably, much will change in him, and those who are interested in his career will watch with pleasure his services to art. Meanwhile, we wish him every success along the path he has chosen.

B. HENDERSON

Download the August issue

No comments yet